Births

| | This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (November 2023) |

| Millennium: | 1st millennium BC |

|---|---|

| Centuries: | |

| Decades: | |

| Years: |

| 841 BC by topic |

| Politics |

|---|

| Categories |

| Gregorian calendar | 841 BC DCCCXLI BC |

| Ancient Egypt era | XXIII dynasty, 40 |

| Ancient Greek era | 65 before 1st Olympiad |

| Assyrian calendar | 3910 |

| Balinese saka calendar | N/A |

| Bengali calendar | −1433 |

| Berber calendar | 110 |

| Buddhist calendar | −296 |

| Burmese calendar | −1478 |

| Byzantine calendar | 4668–4669 |

| Chinese calendar | 己未年 (Earth Goat) 1857 or 1650 — to — 庚申年 (Metal Monkey) 1858 or 1651 |

| Coptic calendar | −1124 – −1123 |

| Discordian calendar | 326 |

| Ethiopian calendar | −848 – −847 |

| Hebrew calendar | 2920–2921 |

| Hindu calendars | |

| - Vikram Samvat | −784 – −783 |

| - Shaka Samvat | N/A |

| - Kali Yuga | 2260–2261 |

| Holocene calendar | 9160 |

| Iranian calendar | 1462 BP – 1461 BP |

| Islamic calendar | 1507 BH – 1506 BH |

| Javanese calendar | N/A |

| Julian calendar | N/A |

| Korean calendar | 1493 |

| Minguo calendar | 2752 before ROC 民前2752年 |

| Nanakshahi calendar | −2308 |

| Thai solar calendar | −298 – −297 |

| Tibetan calendar | 阴土羊年 (female Earth-Goat) −714 or −1095 or −1867 — to — 阳金猴年 (male Iron-Monkey) −713 or −1094 or −1866 |

The year 841 BC, is highly significant in ancient Chinese history, in that Sima Qian was able to construct a year-by-year chronology back to that point. [1] Any earlier events in Chinese history cannot be confidently dated by historians. [2]

| | This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (November 2023) |

Sima Qian was a Chinese historian of the early Han dynasty. He is considered the father of Chinese historiography for his Records of the Grand Historian, a general history of China covering more than two thousand years beginning from the rise of the legendary Yellow Emperor and the formation of the first Chinese polity to the reigning sovereign of Sima Qian's time, Emperor Wu of Han. As the first universal history of the world as it was known to the ancient Chinese, the Records of the Grand Historian served as a model for official history-writing for subsequent Chinese dynasties and the Chinese cultural sphere up until the 20th century.

The 9th century BC started the first day of 900 BC and ended the last day of 801 BC. It was a period of great change for several civilizations. In Africa, Carthage is founded by the Phoenicians. In Egypt, a severe flood covers the floor of Luxor temple, and years later, a civil war starts.

The Xia dynasty was a royal dynasty of China and typically considered the first dynasty in traditional Chinese historiography. According to tradition, it was established by the legendary Yu the Great, after Shun, the last of the Five Emperors, gave the throne to him. In traditional historiography, the Xia was succeeded by the Shang dynasty.

This article concerns the period 849 BC – 840 BC.

Qin Shi Huang was the founder of the Qin dynasty and the first Emperor of China. Rather than maintain the title of "king" (王) borne by the previous Shang and Zhou rulers, he assumed the invented title of "emperor" (皇帝), which would see continuous use by monarchs in China for the next two millennia.

The Spring and Autumn period or Chunqiu in Chinese history lasted from approximately 770 to 481 BCE which corresponds roughly to the first half of the Eastern Zhou period. The period's name derives from the Spring and Autumn Annals, a chronicle of the state of Lu between 722 and 481 BCE, which tradition associates with Confucius. During this period, royal control over the various local polities eroded as regional lords increasingly exercised political autonomy, negotiating their own alliances, waging wars amongst themselves, up to defying the king's court in Luoyi. The gradual Partition of Jin, one of the most powerful states, is generally considered to mark the end of the Spring and Autumn period and the beginning of the Warring States period.

Records of the Grand Historian, also known by its Chinese name Shiji, is a monumental history of China that is the first of China's 24 dynastic histories. The Records was written in the late 2nd century BC to early 1st century BC by the ancient Chinese historian Sima Qian, whose father Sima Tan had begun it several decades earlier. The work covers a 2,500-year period from the age of the legendary Yellow Emperor to the reign of Emperor Wu of Han in the author's own time, and describes the world as it was known to the Chinese of the Western Han dynasty.

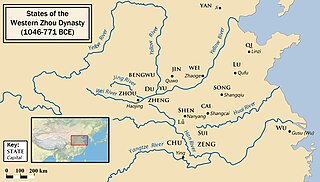

The Western Zhou was a period of Chinese history, approximately first half of the Zhou dynasty, before the period of the Eastern Zhou. It began when King Wu of Zhou overthrew the Shang dynasty at the Battle of Muye and ended when Quanrong pastoralists sacked its capital Haojing and killed King You of Zhou in 771 BC.

Wei was one of the seven major states during the Warring States period of ancient China. It was created from the three-way Partition of Jin, together with Han and Zhao. Its territory lay between the states of Qin and Qi and included parts of modern-day Henan, Hebei, Shanxi, and Shandong. After its capital was moved from Anyi to Daliang during the reign of King Hui, Wei was also called Liang.

King Li of Zhou, personal name Ji Hu, was the tenth king of the Chinese Zhou Dynasty. Estimated dates of his reign] are 877–841 BC or 857–842 BC.

King Ping of Zhou, personal name Ji Yijiu, was the thirteenth king of the Zhou dynasty and the first of the Eastern Zhou dynasty.

King Xiang of Zhou, personal name Ji Zheng, was the eighteenth king of the Chinese Zhou dynasty and the sixth of the Eastern Zhou. He was a successor of his father King Hui of Zhou.

The Qin officially the Great Qin, was an ancient Chinese state during the Zhou dynasty. It is traditionally dated to 897 BC. The Qin state originated from a reconquest of western lands that had previously been lost to the Xirong. Its location at the western edge of Chinese civilisation allowed for expansion and development that was not available to its rivals in the North China Plain.

Chu, or Ch'u in Wade–Giles romanization, was a Zhou dynasty vassal state. Their first ruler was King Wu of Chu in the early 8th century BC. Chu was located in the south of the Zhou heartland and lasted during the Spring and Autumn period. At the end of the Warring States period it was destroyed by the Qin in 223 BC during the Qin's wars of unification.

The Guoyu, usually translated Discourses of the States, is an ancient Chinese text that consists of a collection of speeches attributed to rulers and other men from the Spring and Autumn period (771–476 BC). It comprises a total of 240 speeches, ranging from the reign of King Mu of Zhou to the execution of the Jin minister Zhibo in 453 BC. Guoyu was probably compiled beginning in the 5th century BC and continuing to the late 4th century BC. The earliest chapter of the compilation is the Discourses of Zhou.

The Gonghe Regency was an interregnum period in Chinese history from 841 BC to 828 BC, after King Li of Zhou was exiled by his nobles during the Compatriots Rebellion, when the Chinese people rioted against their old corrupt king. It lasted until the ascension of King Li's son, King Xuan of Zhou.

Duke Huan of Qi, personal name Xiǎobái (小白), was the ruler of the State of Qi from 685 to 643 BC. Living during the chaotic Spring and Autumn period, as the Zhou dynasty's former vassal states fought each other for supremacy, Duke Huan and his long-time advisor Guan Zhong managed to transform Qi into China's most powerful polity. Duke Huan was eventually recognized by most of the Zhou states as well as the Zhou royal family as Hegemon of China. In this position, he fought off invasions of China by non-Zhou peoples and attempted to restore order throughout the lands. Toward the end of his more than forty-year-long reign, however, Duke Huan's power began to decline as he grew ill and Qi came to be embroiled in factional strife. Following his death in 643 BC, Qi completely lost its predominance.

The Xia–Shang–Zhou Chronology Project was a multi-disciplinary project commissioned by the People's Republic of China in 1996 to determine with accuracy the location and time frame of the Xia, Shang, and Zhou dynasties.

Duke Dao of Jin was from 573 to 558 BC the ruler of the State of Jin, a major power during the Spring and Autumn period of ancient China. His ancestral name was Ji, given name Zhou (周), and Duke Dao was his posthumous title.

Dai Commandery was a commandery (jùn) of the state of Zhao established c. 300 BC and of northern imperial Chinese dynasties until the time of the Emperor Wen of the Sui dynasty. It occupied lands in what is now Hebei, Shanxi, and Inner Mongolia. Its seat was usually at Dai or Daixian, although it was moved to Gaoliu during the Eastern Han.