Related Research Articles

All's Well That Ends Well is a play by William Shakespeare, published in the First Folio in 1623, where it is listed among the comedies. There is a debate regarding the dating of the composition of the play, with possible dates ranging from 1598 to 1608.

The Merry Wives of Windsor or Sir John Falstaff and the Merry Wives of Windsor is a comedy by William Shakespeare first published in 1602, though believed to have been written in or before 1597. The Windsor of the play's title is a reference to the town of Windsor, also the location of Windsor Castle in Berkshire, England. Though nominally set in the reign of Henry IV or early in the reign of Henry V, the play makes no pretence to exist outside contemporary Elizabethan-era English middle-class life. It features the character Sir John Falstaff, the fat knight who had previously been featured in Henry IV, Part 1 and Part 2. It has been adapted for the opera at least ten times. The play is one of Shakespeare's lesser-regarded works among literary critics. Tradition has it that The Merry Wives of Windsor was written at the request of Queen Elizabeth I. After watching Henry IV Part I, she asked Shakespeare to write a play depicting Falstaff in love.

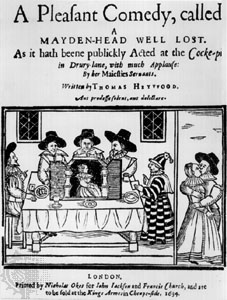

Thomas Heywood was an English playwright, actor, and author. His main contributions were to late Elizabethan and early Jacobean theatre. He is best known for his masterpiece A Woman Killed with Kindness, a domestic tragedy, which was first performed in 1603 at the Rose Theatre by the Worcester's Men company. He was a prolific writer, claiming to have had "an entire hand or at least a maine finger in two hundred and twenty plays", although only a fraction of his work has survived.

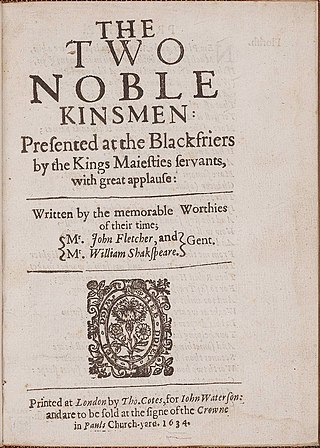

The Two Noble Kinsmen is a Jacobean tragicomedy, first published in 1634 and attributed jointly to John Fletcher and William Shakespeare. Its plot derives from "The Knight's Tale" in Geoffrey Chaucer's The Canterbury Tales, which had already been dramatised at least twice before. This play is believed to have been William Shakespeare's final play before he retired to Stratford-upon-Avon and died three years later.

Sanditon (1817) is an unfinished novel by the English writer Jane Austen. In January 1817, Austen began work on a new novel she called The Brothers, later titled Sanditon, and completed eleven chapters before stopping work in mid-March 1817, probably because of illness. R.W. Chapman first published a full transcription of the novel in 1925 under the name Fragment of a Novel.

The Rover or The Banish'd Cavaliers is a play in two parts that is written by the English author Aphra Behn. It is a revision of Thomas Killigrew's play Thomaso, or The Wanderer (1664), and features multiple plot lines, dealing with the amorous adventures of a group of Englishmen and women in Naples at Carnival time. According to Restoration poet John Dryden, it "lacks the manly vitality of Killigrew's play, but shows greater refinement of expression." The play stood for three centuries as "Behn's most popular and most respected play."

A Yorkshire Tragedy is an early Jacobean era stage play, a domestic tragedy printed in 1608. The play was originally assigned to William Shakespeare, though the modern critical consensus rejects this attribution, favouring Thomas Middleton.

The Witch of Edmonton is an English Jacobean play, written by William Rowley, Thomas Dekker and John Ford in 1621.

The Monastery: a Romance (1820) is a historical novel by Walter Scott, one of the Waverley novels. Set in the Scottish Borders in the 1550s on the eve of the Reformation, it is centred on Melrose Abbey.

MichaelmasTerm is a Jacobean comedy by Thomas Middleton. It was first performed in 1604 by the Children of Paul's, and was entered into the Stationers' Register on 15 May 1607, and published in quarto later that year by Arthur Johnson. A second quarto was printed in 1630 by the bookseller Richard Meighen.

A Mad World, My Masters is a Jacobean stage play written by Thomas Middleton, a comedy first performed around 1605 and first published in 1608. The title had been used by a pamphleteer, Nicholas Breton, in 1603, and was later the origin for the title of Stanley Kramer's 1963 film, It's a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World.

A Fair Quarrel is a Jacobean tragicomedy, a collaboration between Thomas Middleton and William Rowley that was first published in 1617.

The Late Lancashire Witches is a Caroline-era stage play and written by Thomas Heywood and Richard Brome, published in 1634. The play is a topical melodrama on the subject of the witchcraft controversy that arose in Lancashire in 1633.

[[File:Swetnam, the Woman-hatrgyujyuyf er, arraigned by women.jpg|thumb|Swetnam, the Woman-hater, arraigned by women, printed by William Stansby for Richard Meighen, 1620]] Swetnam the Woman-Hater Arraigned by Women is a Jacobean era stage play, an anonymous comedy that was part of a controversy of the 1615–20 period.

The Woman in White (1997) is a BBC television adaptation based on the 1859 novel of the same name by Wilkie Collins. Unlike the epistolary style of the novel, the 2-hour dramatisation uses Marian as the main character. She bookends the film with her narration. It was nominated for the BAFTA TV Award for Best Drama Serial in 1998.

Fortune by Land and Sea is a Jacobean era stage play, a romantic melodrama written by Thomas Heywood and William Rowley. The play has attracted the attention of modern critics for its juxtaposition of the themes of primogeniture and piracy.

The English Traveller is a seventeenth-century tragicomedy in five acts written by Thomas Heywood, and named as such by the playwright. The play was first performed around the year 1627, and the first printed edition came out in 1633.

The Wise Woman of Hoxton is a city comedy by the early modern English playwright Thomas Heywood. It was published under the title The Wise-Woman of Hogsdon in 1638, though it was probably first performed c. 1604 by the Queen's Men company, either at The Curtain or perhaps The Red Bull. The play is set in Hoxton, an area that at the time was outside the boundaries of the city of London and notorious for its entertainments and recreations. The Victorian critic F. G. Fleay suggested that Heywood, who was also an actor, originally played the part of Sencer. It has often been compared with Ben Jonson's comic masterpiece The Alchemist (1610)—the poet T. S. Eliot, for example, argued that with this play Heywood "succeeds with something not too far below Jonson to be comparable to that master's work".

The Busie Body is a Restoration comedy written by Susanna Centlivre and first performed at the Drury Lane Theatre in 1709. It focuses on the legalities of what constitutes a marriage, and how children might subvert parental power over whom they can marry. The Busie Body was the most popular female authored-play of the eighteenth century, and became a stock piece of most anglophone theatres during the period.

References

- ↑ "A Woman Killed with Kindness". F. Griffiths. 1907.

- ↑ Logan, Terence P., and Denzell S. Smith, eds., The Popular School: A Survey and Bibliography of Recent Studies in English Renaissance Drama, Lincoln, NE, University of Nebraska Press, 1975; pp. 107–9.

- ↑ Chambers, E. K. The Elizabethan Stage, 4 Volumes, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1923; Vol. 3, pp. 341–2.

- ↑ Frey, Christopher; Lieblein, Leanore (2004), "'My breasts sear'd': The Self-Starved Female Body and "A Woman Killed with Kindness"", Early Theatre, 7 (1): 45–66, doi: 10.12745/et.7.1.670 , JSTOR 43500473