Islamic art is a part of Islamic culture and encompasses the visual arts produced since the 7th century CE by people who lived within territories inhabited or ruled by Muslim populations. Referring to characteristic traditions across a wide range of lands, periods, and genres, Islamic art is a concept used first by Western art historians in the late 19th century. Public Islamic art is traditionally non-representational, except for the widespread use of plant forms, usually in varieties of the spiralling arabesque. These are often combined with Islamic calligraphy, geometric patterns in styles that are typically found in a wide variety of media, from small objects in ceramic or metalwork to large decorative schemes in tiling on the outside and inside of large buildings, including mosques. Other forms of Islamic art include Islamic miniature painting, artefacts like Islamic glass or pottery, and textile arts, such as carpets and embroidery.

A kaftan or caftan is a variant of the robe or tunic. Originating in Asia, it has been worn by a number of cultures around the world for thousands of years. In Russian usage, kaftan instead refers to a style of men's long suit with tight sleeves.

A miniature is a small illustration used to decorate an ancient or medieval illuminated manuscript; the simple illustrations of the early codices having been miniated or delineated with that pigment. The generally small scale of such medieval pictures has led to etymological confusion with minuteness and to its application to small paintings, especially portrait miniatures, which did however grow from the same tradition and at least initially used similar techniques.

Levnî Abdulcelil Çelebi (1680s–1732) was an early 18th century Ottoman court painter under the Sultans Mustafa II and Ahmed III. He was a prominent Ottoman miniaturist during the Tulip Period, well-regarded for his traditional yet innovative style.

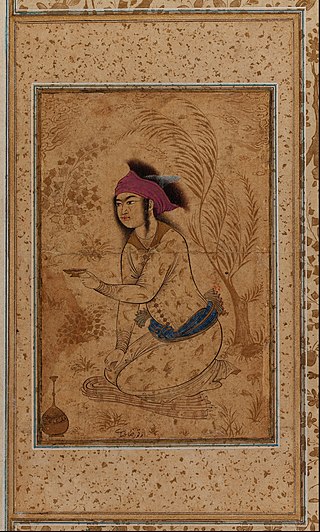

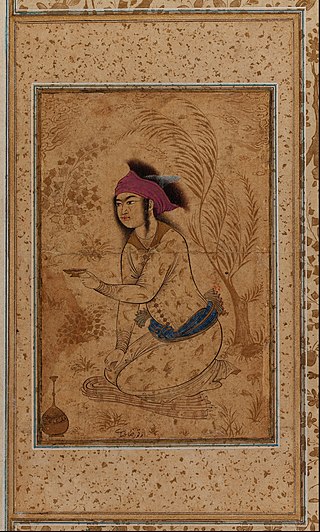

Kamāl ud-Dīn Behzād, also known as Kamal al-din Bihzad or Kamaleddin Behzād, was a Persian painter and head of the royal ateliers in Herat and Tabriz during the late Timurid and early Safavid Persian periods. He is regarded as marking the highpoint of the great tradition of Islamic miniature painting. He was very prominent in his role as kitābdār in the Herat Academy as well as his position in the Royal Library in the city of Herat. His art is unique in that it includes the common geometric attributes of Persian painting, while also inserting his own style, such as vast empty spaces to which the subject of the painting dances around. His art includes masterful use of value and individuality of character, with one of his most famous pieces being "The Seduction of Yusuf”' from Sa'di's Bustan of 1488. Behzād's fame and renown in his lifetime inspired many during, and after, his life to copy his style and works due to the wide praise they received. Due to the great number of copies and difficulty with tracing origin of works, there is a large amount of contemporary work into proper attribution.

Indian painting has a very long tradition and history in Indian art, though because of the climatic conditions very few early examples survive. The earliest Indian paintings were the rock paintings of prehistoric times, such as the petroglyphs found in places like the Bhimbetka rock shelters. Some of the Stone Age rock paintings found among the Bhimbetka rock shelters are approximately 10,000 years old.

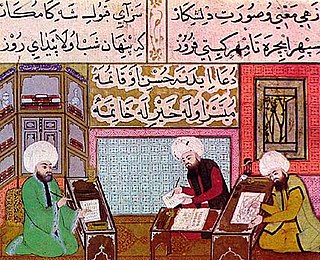

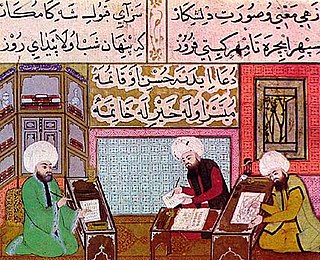

The Siyer-i Nebi is an Ottoman Turkish epic on the life of Muhammad, completed around 1388, written by Mustafa, a Mevlevi dervish on the commission of Sultan Barquq, the Mamluk ruler in Cairo. The text is based on the 13th-century writings of Abu’l Hasan al-Bakri and Ibn Hisham. This epic would later be illustrated by Mustafa ibn Vali in the late 16th century by his patron, Sultan Murad III.

A Persian miniature is a small Persian painting on paper, whether a book illustration or a separate work of art intended to be kept in an album of such works called a muraqqa. The techniques are broadly comparable to the Western Medieval and Byzantine traditions of miniatures in illuminated manuscripts. Although there is an equally well-established Persian tradition of wall-painting, the survival rate and state of preservation of miniatures is better, and miniatures are much the best-known form of Persian painting in the West, and many of the most important examples are in Western, or Turkish, museums. Miniature painting became a significant genre in Persian art in the 13th century, receiving Chinese influence after the Mongol conquests, and the highest point in the tradition was reached in the 15th and 16th centuries. The tradition continued, under some Western influence, after this, and has many modern exponents. The Persian miniature was the dominant influence on other Islamic miniature traditions, principally the Ottoman miniature in Turkey, and the Mughal miniature in the Indian sub-continent.

The Tulip Period, or Tulip Era, is a period in Ottoman history from the Treaty of Passarowitz on 21 July 1718 to the Patrona Halil Revolt on 28 September 1730. This was a relatively peaceful period, during which the Ottoman Empire began to orient itself outwards.

Portrait painting is a genre in painting, where the intent is to represent a specific human subject. The term 'portrait painting' can also describe the actual painted portrait. Portraitists may create their work by commission, for public and private persons, or they may be inspired by admiration or affection for the subject. Portraits often serve as important state and family records, as well as remembrances.

Ottoman miniature or Turkish miniature was a Turkish art form in the Ottoman Empire, which can be linked to the Persian miniature tradition, as well as strong Chinese artistic influences. It was a part of the Ottoman book arts, together with illumination, calligraphy, marbling paper, and bookbinding. The words taswir or nakish were used to define the art of miniature painting in Ottoman Turkish. The studios the artists worked in were called Nakkashanes.

Turkish art refers to all works of visual art originating from the geographical area of what is present day Turkey since the arrival of the Turks in the Middle Ages. Turkey also was the home of much significant art produced by earlier cultures, including the Hittites, Ancient Greeks, and Byzantines. Ottoman art is therefore the dominant element of Turkish art before the 20th century, although the Seljuks and other earlier Turks also contributed. The 16th and 17th centuries are generally recognized as the finest period for art in the Ottoman Empire, much of it associated with the huge Imperial court. In particular the long reign of Suleiman the Magnificent from 1520 to 1566 brought a combination, rare in any ruling dynasty, of political and military success with strong encouragement of the arts.

'Abd al-Ṣamad or Khwaja 'Abd-us-Ṣamad was a 16th century painter of Persian miniatures who moved to India and became one of the founding masters of the Mughal miniature tradition, and later the holder of a number of senior administrative roles. 'Abd's career under the Mughals, from about 1550 to 1595, is relatively well documented, and a number of paintings are authorised to him from this period. From about 1572 he headed the imperial workshop of the Emperor Akbar and "it was under his guidance that Mughal style came to maturity". It has recently been contended by a leading specialist, Barbara Brend, that Samad is the same person as Mirza Ali, a Persian artist whose documented career seems to end at the same time as Abd al-Samad appears working for the Mughals.

Jordanian art has a very ancient history. Some of the earliest figurines, found at Aïn Ghazal, near Amman, have been dated to the Neolithic period. A distinct Jordanian aesthetic in art and architecture emerged as part of a broader Islamic art tradition which flourished from the 7th-century. Traditional art and craft is vested in material culture including mosaics, ceramics, weaving, silver work, music, glass-blowing and calligraphy. The rise of colonialism in North Africa and the Middle East, led to a dilution of traditional aesthetics. In the early 20th-century, following the creation of the independent nation of Jordan, a contemporary Jordanian art movement emerged and began to search for a distinctly Jordanian art aesthetic that combined both tradition and contemporary art forms.

Turkish or Ottoman illumination covers non-figurative painted or drawn decorative art in books or on sheets in muraqqa or albums, as opposed to the figurative images of the Ottoman miniature. In Turkish it is called “tezhip”, meaning “ornamenting with gold”. It was a part of the Ottoman Book Arts together with the Ottoman miniature (taswir), calligraphy (hat), bookbinding (cilt) and paper marbling (ebru). In the Ottoman Empire, illuminated and illustrated manuscripts were commissioned by the Sultan or the administrators of the court. In Topkapi Palace, these manuscripts were created by the artists working in Nakkashane, the atelier of the miniature and illumination artists. Both religious and non-religious books could be illuminated. Also sheets for albums levha consisted of illuminated calligraphy (hat) of tughra, religious texts, verses from poems or proverbs, and purely decorative drawings.

A Muraqqa is an album in book form containing Islamic miniature paintings and specimens of Islamic calligraphy, normally from several different sources, and perhaps other matter. The album was popular among collectors in the Islamic world, and by the later 16th century became the predominant format for miniature painting in the Persian Safavid, Mughal and Ottoman empires, greatly affecting the direction taken by the painting traditions of the Persian miniature, Ottoman miniature and Mughal miniature. The album largely replaced the full-scale illustrated manuscript of classics of Persian poetry, which had been the typical vehicle for the finest miniature painters up to that time. The great cost and delay of commissioning a top-quality example of such a work essentially restricted them to the ruler and a handful of other great figures, who usually had to maintain a whole workshop of calligraphers, artists and other craftsmen, with a librarian to manage the whole process.

Persian art or Iranian art has one of the richest art heritages in world history and has been strong in many media including architecture, painting, weaving, pottery, calligraphy, metalworking and sculpture. At different times, influences from the art of neighbouring civilizations have been very important, and latterly Persian art gave and received major influences as part of the wider styles of Islamic art. This article covers the art of Persia up to 1925, and the end of the Qajar dynasty; for later art see Iranian modern and contemporary art, and for traditional crafts see arts of Iran. Rock art in Iran is its most ancient surviving art. Iranian architecture is covered at that article.

The Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp or Houghton Shahnameh is one of the most famous illustrated manuscripts of the Shahnameh, the national epic of Greater Iran, and a high point in the art of the Persian miniature. It is probably the most fully illustrated manuscript of the text ever produced. When created, the manuscript contained 759 pages, 258 of which were miniatures. These miniatures were hand-painted by the artists of the royal workshop in Tabriz under rulers Shah Ismail I and Shah Tahmasp I. Upon its completion, the Shahnameh was gifted to Ottoman Sultan Selim II in 1568. The page size is about 48 x 32 cm, and the text written in Nastaʿlīq script of the highest quality. The manuscript was broken up in the 1970s and pages are now in a number of different collections around the world.

The Saint Gregory the Illuminator Church of Galata is the oldest extant Armenian Apostolic church in Istanbul. It was built in the late 14th century, in the Genoan period, shortly before the fall of Constantinople to the Ottomans. Located in Galata (Karaköy), it is the city's only church built in the traditional style of the Armenian church architecture—namely with a dome with a conical roof.

Georgios Klontzas also known as George Klontzas and Zorzi Cloza dito Cristianopullo. He was a scholar, painter, and manuscript illuminator. He is one of the most influential artists of the post-Byzantine period. He defined the Cretan Renaissance. He worked for both Catholic and Orthodox patrons. His artistic output included: icons, miniatures, triptychs, and illuminated manuscripts. He is known for occupying his icons with countless figures. The technique is extremely complex and unique to Klontzas. Andreas Pavias attempted this technique in the Crucifixion of Jesus. Klontzas's painting All Creation rejoices in thee is his most popular work. Klontzas influenced Theodore Poulakis he created an extremely similar painting called In Thee Rejoiceth. Klontzas's work is strongly influenced by the Venetian school. His triptychs strongly resemble the works of Gentile da Fabriano, namely the Intercession Altarpiece. Klontzas's Last Judgement resembles Michelangelo's Last Judgement in the Sistine Chapel. There are very close similarities. There is no indication that Klontzas saw the work but it is a possibility. According to the Institute of Neohellenic Research fifty-four items of his art exist today.