An arch is a curved vertical structure spanning an open space underneath it. Arch can either support the load above it or perform a purely decorative role. The arch dates back to fourth millennium BC, but became popular only after its adoption by the Romans in the 4th century BC.

Gothic architecture is an architectural style that was prevalent in Europe from the late 12th to the 16th century, during the High and Late Middle Ages, surviving into the 17th and 18th centuries in some areas. It evolved from Romanesque architecture and was succeeded by Renaissance architecture. It originated in the Île-de-France and Picardy regions of northern France. The style at the time was sometimes known as opus Francigenum ; the term Gothic was first applied contemptuously during the later Renaissance, by those ambitious to revive the architecture of classical antiquity.

A dome is an architectural element similar to the hollow upper half of a sphere. There is significant overlap with the term cupola, which may also refer to a dome or a structure on top of a dome. The precise definition of a dome has been a matter of controversy and there are a wide variety of forms and specialized terms to describe them.

An ogive is the roundly tapered end of a two-dimensional or three-dimensional object. Ogive curves and surfaces are used in engineering, architecture, woodworking, and munitions.

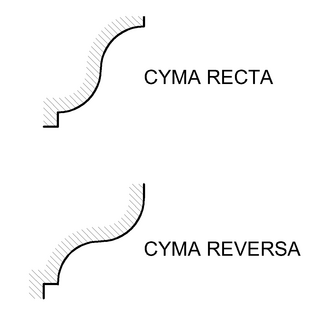

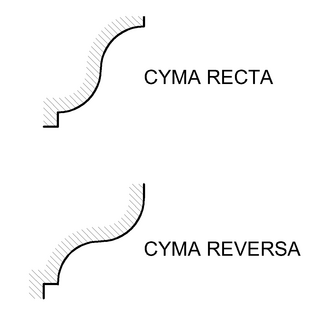

An ogee ( ) is an object, element, or curve—often seen in architecture and building trades—that has a serpentine- or extended S-shape (sigmoid). Ogees consist of a "double curve", the combination of two semicircular curves or arcs that, as a result of a point of inflection from concave to convex or vice versa, have ends of the overall curve that point in opposite directions.

Mihrab is a niche in the wall of a mosque that indicates the qibla, the direction of the Kaaba in Mecca towards which Muslims should face when praying. The wall in which a mihrab appears is thus the "qibla wall".

The flying buttress is a specific form of buttress composed of an arch that extends from the upper portion of a wall to a pier of great mass, in order to convey to the ground the lateral forces that push a wall outwards, which are forces that arise from vaulted ceilings of stone and from wind-loading on roofs.

In architecture, a niche is a recess or cavity constructed in the thickness of a wall for the reception of decorative objects such as statues, busts, urns, and vases. In Classical architecture examples are an exedra or an apse that has been reduced in size, retaining the half-dome heading usual for an apse. In the first century B.C, there was no exact mention of niches, but rather a zotheca or small room. These rooms closely resemble alcoves similar to a niche but slightly larger. Different sizes and sculpture methods suggest the term niche was understood. Greeks and Romans especially, used niches for important family tombs.

An archivolt is an ornamental moulding or band following the curve on the underside of an arch. It is composed of bands of ornamental mouldings surrounding an arched opening, corresponding to the architrave in the case of a rectangular opening. The word is sometimes used to refer to the under-side or inner curve of the arch itself. Most commonly archivolts are found as a feature of the arches of church portals. The mouldings and sculptures on these archivolts are used to convey a theological story or depict religious figures and ideologies of the church in order to represent the gateway between the holy space of the church and the external world. The presence of archivolts on churches is seen throughout history, although their design, both architecturally and artistically, is heavily influenced by the period they were built in and the churches they were designed for.

The Mosque–Cathedral of Córdoba, officially known by its ecclesiastical name of Cathedral of Our Lady of the Assumption, is the cathedral of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Córdoba dedicated to the Assumption of Mary and located in the Spanish region of Andalusia. Due to its status as a former mosque, it is also known as the Mezquita and as the Great Mosque of Córdoba.

Tracery is an architectural device by which windows are divided into sections of various proportions by stone bars or ribs of moulding. Most commonly, it refers to the stonework elements that support the glass in a window. The purpose of the device is practical as well as decorative, because the increasingly large windows of Gothic buildings needed maximum support against the wind. The term probably derives from the tracing floors on which the complex patterns of windows were laid out in late Gothic architecture. Tracery can be found on the exterior of buildings as well as the interior.

Flamboyant is a form of late Gothic architecture that developed in Europe in the Late Middle Ages and Renaissance, from around 1375 to the mid-16th century. In the French timetable of styles, as defined by French scholars, it is the fourth phase of Gothic style, preceded by Primary Gothic, Classic Gothic and Rayonnant Gothic.

A four-centred arch or four-centered arch is a low, wide type of arch with a pointed apex. Its structure is achieved by drafting two arcs which rise steeply from each springing point on a small radius, and then turning into two arches with a wide radius and much lower springing point. It is a pointed sub-type of the general flattened depressed arch. This type of arch uses space efficiently and decoratively when used for doorways. It is also employed as a wall decoration in which arcade and window openings form part of the whole decorative surface. Two of the most notable types are known as the Persian arch, which is moderately "depressed" and found in Islamic architecture, and the Tudor arch, which is much flatter and found in English architecture. Another variant, the keel arch, has partially straight rather than curved sides and developed in Fatimid architecture.

English Gothic is an architectural style that flourished from the late 12th until the mid-17th century. The style was most prominently used in the construction of cathedrals and churches. Gothic architecture's defining features are pointed arches, rib vaults, buttresses, and extensive use of stained glass. Combined, these features allowed the creation of buildings of unprecedented height and grandeur, filled with light from large stained glass windows. Important examples include Westminster Abbey, Canterbury Cathedral and Salisbury Cathedral. The Gothic style endured in England much longer than in Continental Europe.

The horseshoe arch, also called the Moorish arch and the keyhole arch, is a type of arch in which the circular curve is continued below the horizontal line of its diameter, so that the opening at the bottom of the arch is narrower than the arch's full span. Evidence for the earliest uses of this form are found in Late Antique and Sasanian architecture, but it became emblematic of Islamic architecture, especially Moorish architecture. It also made later appearances in Moorish Revival and Art Nouveau styles. Horseshoe arches can take rounded, pointed or lobed form.

The Arab-Ata Mausoleum is a cubical, domed brick mausoleum built in 977-78 in the village of Tim, Samarqand Region, Uzbekistan. Built during the Samanid Empire, the Arab-Ata Mausoleum was among the earliest buildings to include three notable features of Islamic architecture: the muqarnas, mihrab, and pishtaq. Following the appearance of the mihrab in the Arab-Ata mausoleum, mihrabs became a more common feature in mausoleums from the tenth century on. The Arab-Ata is the earliest dated example of a pishtaq, with it becoming a staple of Islamic architecture. It has been proposed that the pishtaq developed further with the many Seljuq domes from the eleventh and twelfth centuries.

The Great Mosque of Mahdiya is a mosque that was built in the tenth century in Mahdia, Tunisia. Located on the southern side of the peninsula on which the old city was located, construction of the mosque was initiated in 916, when the city was founded by the Fatimid caliph Abdallah al-Mahdi, to serve as the new city's main mosque. Most of the Fatimid-era city and its structures have since disappeared. The current mosque was largely reconstructed by archeologists in the 1960s, with the exception of its preserved entrance façade.

The early domes of the Middle Ages, particularly in those areas recently under Byzantine control, were an extension of earlier Roman architecture. The domed church architecture of Italy from the sixth to the eighth centuries followed that of the Byzantine provinces and, although this influence diminishes under Charlemagne, it continued on in Venice, Southern Italy, and Sicily. Charlemagne's Palatine Chapel is a notable exception, being influenced by Byzantine models from Ravenna and Constantinople. The Dome of the Rock, an Umayyad Muslim religious shrine built in Jerusalem, was designed similarly to nearby Byzantine martyria and Christian churches. Domes were also built as part of Muslim palaces, throne halls, pavilions, and baths, and blended elements of both Byzantine and Persian architecture, using both pendentives and squinches. The origin of the crossed-arch dome type is debated, but the earliest known example is from the tenth century at the Great Mosque of Córdoba. In Egypt, a "keel" shaped dome profile was characteristic of Fatimid architecture. The use of squinches became widespread in the Islamic world by the tenth and eleventh centuries. Bulbous domes were used to cover large buildings in Syria after the eleventh century, following an architectural revival there, and the present shape of the Dome of the Rock's dome likely dates from this time.

Domes built in the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries relied primarily on empirical techniques and oral traditions rather than the architectural treatises of the time, but the study of dome structures changed radically due to developments in mathematics and the study of statics. Analytical approaches were developed and the ideal shape for a dome was debated, but these approaches were often considered too theoretical to be used in construction.

A pointed arch, ogival arch, or Gothic arch is an arch with a pointed crown meet at an angle at the top of the arch. Also known as a two-centred arch, its form is derived from the intersection of two circles. This architectural element was particularly important in Gothic architecture. The earliest use of a pointed arch dates back to bronze-age Nippur. As a structural feature, it was first used in eastern Christian architecture, Byzantine architecture and Sasanian architecture, but in the 12th century it came into use in France and England as an important structural element, in combination with other elements, such as the rib vault and later the flying buttress. These allowed the construction of cathedrals, palaces and other buildings with dramatically greater height and larger windows which filled them with light.