The Republic of South Africa is a unitary parliamentary democratic republic. The President of South Africa serves both as head of state and as head of government. The President is elected by the National Assembly and must retain the confidence of the Assembly in order to remain in office. South Africans also elect provincial legislatures which govern each of the country's nine provinces.

The Freedom Front Plus is a right-wing political party in South Africa that was formed in 1994. It is led by Pieter Groenewald.

The Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging, commonly known by its abbreviation AWB, is an Afrikaner nationalist, neo-Nazi political party in South Africa. Since its founding in 1973 by Eugène Terre'Blanche and six other far-right Afrikaners, it has been dedicated to secessionist Afrikaner nationalism and the creation of an independent Boer-Afrikaner republic or "Volkstaat/Boerestaat" in part of South Africa. During bilateral negotiations to end apartheid in the early 1990s, the organisation terrorised and killed black South Africans.

Orania is an Afrikaner nationalist, South African town founded by Afrikaners. It is located along the Orange River in the Karoo region of the Northern Cape province. The town is split in two halves by the R369 road, and is 871 kilometres (541 mi) from Cape Town and approximately 680 kilometres (420 mi) from Pretoria. Its climate is semi-arid.

1994 in South Africa saw the transition from South Africa's National Party government who had ruled the country since 1948 and had advocated the apartheid system for most of its history, to the African National Congress (ANC) who had been outlawed in South Africa since the 1950s for its opposition to apartheid. The ANC won a majority in the first multiracial election held under universal suffrage. Previously, only white people were allowed to vote. There were some incidents of violence in the Bantustans leading up to the elections as some leaders of the Bantusans opposed participation in the elections, while other citizens wanted to vote and become part of South Africa. There were also bombings aimed at both the African National Congress and the National Party and politically-motivated murders of leaders of the opposing ANC and Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP).

The Herstigte Nasionale Party is a South African political party which was formed as a far-right splinter group of the now defunct National Party in 1969. The party name was commonly abbreviated as HNP, evoking the Herenigde Nasionale Party, although colloquially they were also known as the Herstigtes. The party is, unlike other splinter factions from the National Party, still active but politically irrelevant.

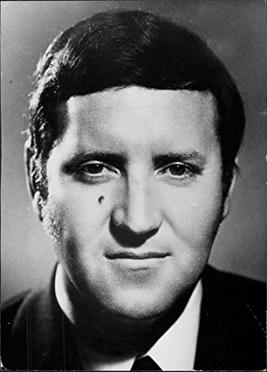

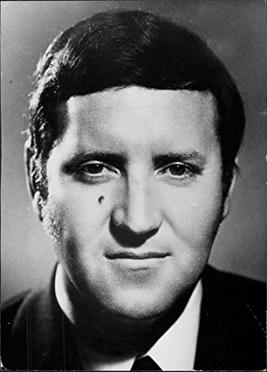

General Constand Laubscher Viljoen was a South African military commander and politician. He co-founded the Afrikaner Volksfront and later founded the Freedom Front. He is partly credited with having prevented the outbreak of armed violence by disaffected white South Africans prior to post-apartheid general elections.

A Volkstaat, also called a Boerestaat, is a proposed White homeland for Afrikaners within the borders of South Africa, most commonly proposed as a fully independent Boer/Afrikaner nation. The proposed state would exclude Afrikaans-speaking Coloureds but accept South Africans of English ancestry and other White South Africans, if they accept Afrikaner culture and customs.

A referendum on ending apartheid was held in South Africa on 17 March 1992. The referendum was limited to white South African voters, who were asked whether or not they supported the negotiated reforms begun by State President F. W. de Klerk two years earlier, in which he proposed to end the apartheid system that had been implemented since 1948. The result of the election was a large victory for the "yes" side, which ultimately resulted in apartheid being lifted. Universal suffrage was introduced two years later.

The Afrikaner Volksfront was a separatist umbrella organisation uniting a number of right-wing Afrikaner organisations in South Africa in the early 1990s.

The apartheid system in South Africa was ended through a series of bilateral and multi-party negotiations between 1990 and 1993. The negotiations culminated in the passage of a new interim Constitution in 1993, a precursor to the Constitution of 1996; and in South Africa's first non-racial elections in 1994, won by the African National Congress (ANC) liberation movement.

Afrikaner nationalism is a nationalistic political ideology created by Afrikaners residing in Southern Africa during the Victorian era. The ideology was developed in response to the significant events in Afrikaner history such as the Great Trek, the First and Second Boer Wars and the resulting anti-British sentiment that developed among Afrikaners and opposition to South Africa's entry into World War I.

The 1994 Bophuthatswana crisis was a major political crisis which began after Lucas Mangope, the president of Bophuthatswana, a nominally independent South African bantustan created under apartheid, attempted to crush widespread labour unrest and popular demonstrations demanding the incorporation of the territory into South Africa pending non-racial elections later that year. Violent protests immediately broke out following President Mangope's announcement on 7 March that Bophuthatswana would boycott the South African general elections. This was escalated by the arrival of right-wing Afrikaner militias seeking to preserve the Mangope government. The predominantly black Bophuthatswana Defence Force and police refused to cooperate with the white extremists and mutinied, then forced the Afrikaner militias to leave Bophuthatswana. The South African military entered Bophuthatswana and restored order on 12 March.

The Volkstaat Council was an organisation of 20 people, created by the South African government, to serve as a constitutional mechanism to enable proponents of the idea of a Volkstaat to constitutionally pursue the establishment of such a Volkstaat.

Carel Willem Hendrik Boshoff was a South African professor of theology and Afrikaner white nationalist.

The National Conservative Party of South Africa is an Afrikaner nationalist political party formed on 16 April 2016 in Pretoria.

Rowan Cronjé was a Rhodesian politician who served in the cabinet under prime ministers Ian Smith and Abel Muzorewa, and was later a Zimbabwean MP. He emigrated to South Africa in 1985 and served in the government of Bophuthatswana.

The Orania Representative Council is the local municipal representative council in the Northern Cape province of South Africa that governs the Afrikaner-town of Orania in the Pixley ka Seme District Municipality. During the implementation of a new municipal system in South Africa in 2000, the Orania Representative Council was the only representative council that was not abolished. Therefore, the Orania Representative Council is the only municipal body that still uses the old (pre-2000) municipal structure, based on the Local Government Transition Act of 1993.

A White ethnostate is a proposed type of state in which residence or citizenship would be limited to Whites, and non-whites and any other groups not seen as white would be excluded from citizenship. Within the Anglosphere, the natives of their respective countries would also be excluded from citizenship, such as the Indigenous people of the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and South Africa.

Cape independence, also known by the portmanteau CapeXit, is a political movement that seeks the independence of the Western Cape province from South Africa.