Related Research Articles

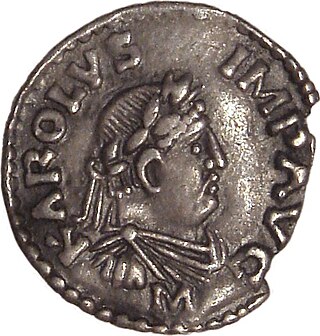

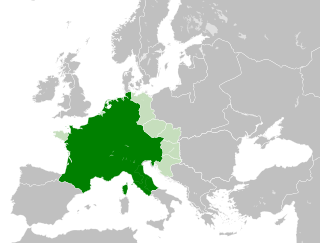

Charlemagne was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and Emperor of what is now known as the Carolingian Empire from 800, holding these titles until his death in 814. He united most of Western and Central Europe, and was the first recognised emperor to rule from the west after the fall of the Western Roman Empire approximately three centuries earlier. Charlemagne's reign was marked by political and social changes that had lasting influence on Europe throughout the Middle Ages.

Louis the Pious, also called the Fair and the Debonaire, was King of the Franks and co-emperor with his father, Charlemagne, from 813. He was also King of Aquitaine from 781. As the only surviving son of Charlemagne and Hildegard, he became the sole ruler of the Franks after his father's death in 814, a position that he held until his death except from November 833 to March 834, when he was deposed.

The Carolingian Empire (800–887) was a Frankish-dominated empire in Western and Central Europe during the Early Middle Ages. It was ruled by the Carolingian dynasty, which had ruled as kings of the Franks since 751 and as kings of the Lombards in Italy from 774. In 800, the Frankish king Charlemagne was crowned emperor in Rome by Pope Leo III in an effort to transfer the status of Roman Empire from the Byzantine Empire to Western Europe. The Carolingian Empire is sometimes considered the first phase in the history of the Holy Roman Empire.

Carloman I, German Karlmann, Karlomann, was king of the Franks from 768 until his death in 771. He was the second surviving son of Pepin the Short and Bertrada of Laon and was a younger brother of Charlemagne. His death allowed Charlemagne to take all of Francia.

Desiderius, also known as Daufer or Dauferius, was king of the Lombards in northern Italy, ruling from 756 to 774. The Frankish king of renown, Charlemagne, married Desiderius's daughter and subsequently conquered his realm. Desiderius is remembered for this connection to Charlemagne and for being the last Lombard ruler to exercise regional kingship.

The Carolingian Renaissance was the first of three medieval renaissances, a period of cultural activity in the Carolingian Empire. Charlemagne's reign led to an intellectual revival beginning in the 8th century and continuing throughout the 9th century, taking inspiration from ancient Roman and Greek culture and the Christian Roman Empire of the fourth century. During this period, there was an increase of literature, writing, visual arts, architecture, music, jurisprudence, liturgical reforms, and scriptural studies. Carolingian schools were effective centers of education, and they served generations of scholars by producing editions and copies of the classics, both Christian and pagan.

A missus dominicus, Latin for "envoy[s] of the lord [ruler]" or palace inspector, also known in Dutch as Zendgraaf, meaning "sent Graf", was an official commissioned by the Frankish king or Holy Roman Emperor to supervise the administration, mainly of justice, in parts of his dominions too remote for frequent personal visits. As such, the missus performed important intermediary functions between royal and local administrations. There are superficial points of comparison with the original Roman corrector, except that the missus was sent out on a regular basis. Four points made the missi effective as instruments of the centralized monarchy: the personal character of the missus, yearly change, isolation from local interests and the free choice of the king.

The Kingdom of the Franks, also known as the Frankish Kingdom, the Frankish Empire or Francia, was the largest post-Roman barbarian kingdom in Western Europe. It was ruled by the Frankish Merovingian and Carolingian dynasties during the Early Middle Ages. Francia was among the last surviving Germanic kingdoms from the Migration Period era.

Rosamond Deborah McKitterick is an English medieval historian. She is an expert on the Frankish kingdoms in the eighth and ninth centuries AD, who uses palaeographical and manuscript studies to illuminate aspects of the political, cultural, intellectual, religious, and social history of the Early Middle Ages. From 1999 until 2016 she was Professor of Medieval History and director of research at the University of Cambridge. She is a Fellow of Sidney Sussex College and Professor Emerita of Medieval History in the University of Cambridge.

A capitulary was a series of legislative or administrative acts emanating from the Frankish court of the Merovingian and Carolingian dynasties, especially that of Charlemagne, the first emperor of the Romans in the west since the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the late 5th century. They were so called because they were formally divided into sections called capitula.

The Saxon Wars were the campaigns and insurrections of the thirty-three years from 772, when Charlemagne first entered Saxony with the intent to conquer, to 804, when the last rebellion of tribesmen was defeated. In all, 18 campaigns were fought, primarily in what is now northern Germany. They resulted in the incorporation of Saxony into the Frankish realm and their forcible conversion from Germanic paganism to Christianity.

The Battle of Tertry was an important engagement in Merovingian Gaul between the forces of Austrasia under Pepin II on one side and those of Neustria and Burgundy on the other. It took place in 687 at Tertry, Somme, and the battle is presented as an heroic account in the Annales mettenses priores. After achieving victory on the battlefield at Tertry, the Austrasians dictated the political future of the Neustrians.

The Abbey of Saint John is an early medieval Benedictine monastery in the Swiss municipality of Val Müstair, in the Canton of Graubünden. By reason of its exceptionally well-preserved heritage of Carolingian art, it has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1983.

The Council of Frankfurt, traditionally also the Council of Frankfort, in 794 was called by Charlemagne, as a meeting of the important churchmen of the Frankish realm. Bishops and priests from Francia, Aquitaine, Italy, and Provence gathered in Franconofurd. The synod, held in June 794, allowed the discussion and resolution of many central religious and political questions.

The Epistola de litteris colendis is a well-known letter addressed by Emperor Charlemagne to Abbot Baugulf of Fulda, probably written sometime in the late 780s to 800s (decade), although the exact date is still debatable. The letter is a very important witness to the Carolingian educational reforms during the Carolingian Renaissance from the late 8th century to the 9th century. The letter shows Emperor Charlemagne's interest in promoting learning and education within his empire.

Capitulatio de partibus Saxoniae was a legal code issued by Charlemagne and promulgated amongst the Saxons during the Saxon Wars. Traditionally dated to Charlemagne's 782 campaign, and occasionally to 785, the much later date of 795 is also considered possible. Despite the laws, some Saxons continued to reject Charlemagne's rule and attempts at Christianization, with some continuing to rebel even after Charlemagne's death . The Saxons responded to Charlemagne's Christianization efforts by destroying encroaching churches and injuring or killing missionary priests and monks, and the law marks Charlemagne's effort "to impose Christianity on the Saxons by the same force that Charlemagne applied in imposing Carolingian political authority".

The medieval renaissances were periods of cultural renewal across medieval Western Europe. These are effectively seen as occurring in three phases - the Carolingian Renaissance, Ottonian Renaissance and the Renaissance of the 12th century.

The Capitulare missorum generale and Capitularia missorum specialia, both issued in 802, were acts of Charlemagne whereby the role and functions of the missi dominici were defined and placed on a permanent footing, as well as specific instructions sent out to the various missatica.

The Codex epistolaris Carolinus is a collection of 99 letters from reigning popes to Carolingian rulers written between 739 and 791.

The Carolingian Church encompasses the practices and institutions of Christianity in the Frankish kingdoms under the rule of the Carolingian dynasty (751-888). In the eighth and ninth centuries, Western Europe witnessed decisive developments in the structure and organisation of the church, relations between secular and religious authorities, monastic life, theology, and artistic endeavours. Christianity was the principal religion of the Carolingian Empire. Through military conquests and missionary activity, Latin Christendom expanded into new areas, such as Saxony and Bohemia. These developments owed much to the leadership of Carolingian rulers themselves, especially Charlemagne and Louis the Pious, whose courts encouraged successive waves of religious reform and viewed Christianity as a unifying force in their empire.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Jeep 2001, pp. 5–6.

- 1 2 Frassetto 2003, p. 88.

- ↑ McKitterick 2008, p. 237.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Kreis 2009.

- 1 2 3 McKitterick 2008, p. 307.

- 1 2 McKitterick 2008, p. 240.

- ↑ Ganshof 1949, p. 527.

- ↑ Ganshof 1949, p. 521.

- 1 2 McKitterick 2008, p. 311.

- ↑ Ganshof 1949, p. 522.

- ↑ King 1987.

- 1 2 3 Frassetto 2003, p. 1.

- ↑ McKitterick 2008, p. 239.

- ↑ McKitterick 2008, p. 341.

- 1 2 McKitterick 2008, p. 263.

- ↑ McKitterick 2008, pp. 264, 266.

- ↑ McKitterick 2008, p. 243.

- ↑ Contreni 1995, p. 726.

- 1 2 Contreni 1995, p. 739.

- ↑ Contreni 1995, p. 746.

- ↑ Contreni 1995, p. 748.

- ↑ Contreni 1995, p. 709.

- ↑ Contreni 1995, p. 747.

Bibliography

- Contreni, John J. (1995). "The Carolingian Renaissance: Education and Literary Culture". In McKitterick, Rosamond (ed.). The New Cambridge Medieval History, Volume 2, c.700–c.900. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-13905571-0.

- Frassetto, Michael (2003). Encyclopedia of Barbarian Europe: Society in Transformation. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-263-9.

- Ganshof, François L. (1949). "Charlemagne". Speculum . 24 (4): 520–528. doi:10.2307/2854638. JSTOR 2854638. S2CID 225087797.

- Jeep, John M., ed. (2001). Medieval Germany: an Encyclopedia. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-8240-7644-3.

- King, P. D. (1987). Charlemagne: Translated Sources. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-9511503-0-6.

- Kreis, Steven (2009). "Charlemagne and the Carolingian Renaissance". The History Guide. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- McKitterick, Rosamond (2008). Charlemagne: the Formation of a European Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-88672-7.