Related Research Articles

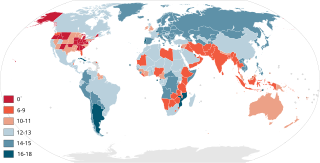

The age of criminal responsibility is the age below which a child is deemed incapable of having committed a criminal offence. In legal terms, it is referred to as a defence/defense of infancy, which is a form of defense known as an excuse so that defendants falling within the definition of an "infant" are excluded from criminal liability for their actions, if at the relevant time, they had not reached an age of criminal responsibility. After reaching the initial age, there may be levels of responsibility dictated by age and the type of offense committed.

The Australian Human Rights Commission is the national human rights institution of Australia, established in 1986 as the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission (HREOC) and renamed in 2008. It is a statutory body funded by, but operating independently of, the Australian Government. It is responsible for investigating alleged infringements of Australia's anti-discrimination legislation in relation to federal agencies.

The Don Dale Youth Detention Centre is a facility for juvenile detention in the Northern Territory, Australia, located in Berrimah, east of Darwin. It is a detention centre for male and female juvenile delinquents. The facility is named after Don Dale, a former Member of the Northern Territory Legislative Assembly from 1983 to 1989 and one-time Minister for Correctional Services.

Human rights in Australia have largely been developed by the democratically elected Australian Parliament through laws in specific contexts and safeguarded by such institutions as the independent judiciary and the High Court, which implement common law, the Australian Constitution, and various other laws of Australia and its states and territories. Australia also has an independent statutory human rights body, the Australian Human Rights Commission, which investigates and conciliates complaints, and more generally promotes human rights through education, discussion and reporting.

Aboriginal deaths in custody is a political and social issue in Australia. It rose in prominence in the early 1980s, with Aboriginal activists campaigning following the death of 16-year-old John Peter Pat in 1983. Subsequent deaths in custody, considered suspicious by families of the deceased, culminated in the 1987 Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody (RCIADIC).

Prostitution in Australia is governed by state and territory laws, which vary considerably, although none ban prostitution outright.

The Northern Territory National Emergency Response, also known as "The Intervention" or the Northern Territory Intervention, and sometimes the abbreviation "NTER" was a package of measures enforced by legislation affecting Indigenous Australians in the Northern Territory (NT) of Australia, which lasted from 2007 until 2012. The measures included restrictions on the consumption of alcohol and pornography, changes to welfare payments, and changes to the delivery and management of education, employment and health services in the Territory.

In Australia, domestic violence (DV) is defined by the Family Law Act 1975. Each state and territory also has its own legislation, some of which broadens the scope of that definition, and terminology varies. It has been identified as a major health and welfare issue. Family violence occurs across all ages and demographic groups, but mostly affects women and children, and at particular risk are three groups: Indigenous, young and pregnant women.

Adoption in Australia deals with the adoption process in the various parts of Australia, whereby a person assumes or acquires the permanent, legal status of parenthood in relation to a child under the age of 18 in place of the child's birth or biological parents. Australia classifies adoptions as local adoptions, and intercountry adoptions. Known child adoptions are a form of local adoptions.

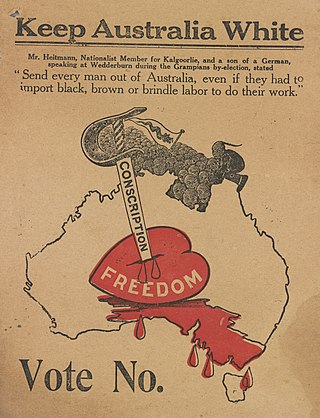

Racism in Australia comprises negative attitudes and views on race or ethnicity which are held by various people and groups in Australia, and have been reflected in discriminatory laws, practices and actions at various times in the history of Australia against racial or ethnic groups.

Indigenous Australians are both convicted of crimes and imprisoned at a disproportionately higher rate in Australia, as well as being over-represented as victims of crime. As of September 2019, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander prisoners represented 28% of the total adult prisoner population, while accounting for 2% of the general adult population. Various explanations have been given for this over-representation, both historical and more recent. Federal and state governments and Indigenous groups have responded with various analyses, programs and measures.

Punishment in Australia arises when an individual has been accused or convicted of breaking the law through the Australian criminal justice system. Australia uses prisons, as well as community corrections. When awaiting trial, prisoners may be kept in specialised remand centres or within other prisons.

Indigenous land rights in Australia, also known as Aboriginal land rights in Australia, are the rights and interests in land of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia; the term may also include the struggle for those rights. Connection to the land and waters is vital in Australian Aboriginal culture and to that of Torres Strait Islander people, and there has been a long battle to gain legal and moral recognition of ownership of the lands and waters occupied by the many peoples prior to colonisation of Australia starting in 1788, and the annexation of the Torres Strait Islands by the colony of Queensland in the 1870s.

Juvenile detention in the Northern Territory is administered by Territory Families, since a departmental reorganisation following the Labor victory at the August 2016 Northern Territory general election. Juvenile detention is mostly operated through two facilities - the Alice Springs Juvenile Holding Centre in Alice Springs, and the Don Dale Juvenile Detention Centre in eastern Darwin. These had previously been administered by the Department of Correctional Services. A juvenile is a child between the age of 10 and 17.

The Royal Commission into the Protection and Detention of Children in the Northern Territory is a Royal Commission established in 2016 by the Australian Government pursuant to the Royal Commissions Act 1902 to inquire into and report upon failings in the child protection and youth detention systems of the Government of the Northern Territory. The establishment of the commission followed revelations broadcast on 25 July 2016 by the ABC TV Four Corners program which showed abuse of juveniles held in the Don Dale Juvenile Detention Centre in Darwin.

Chanston James "Chansey" Paech is an Australian politician. He is a Labor Party member of the Northern Territory Legislative Assembly since 2016, representing the electorate of Namatjira until 2020 and Gwoja thereafter. He is of Arrente, Arabana and Gurindji descent.

A Custody Notification Service (CNS), sometimes referred to as a Custody Notification Scheme, is a 24-hour legal advice and support telephone hotline for any Indigenous Australian person brought into custody, connecting them with lawyers from the Aboriginal legal service operating in their state or territory. It is intended to reduce the high number of Aboriginal deaths in custody by counteracting the effects of institutional racism. Legislation mandating the police to inform the legal service whenever an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander person is brought into custody is seen as essential to ensure compliance and a clear record of events. Where Custody Notification Services have been implemented, there have been reductions in the numbers of Aboriginal deaths in custody.

Crime in Queensland is an on-going political issue. Queensland Police is responsible for providing policing services to Queensland, Australia. Crime statistics for the state are provided on their website. Official records show that reported offences against property and people has declined over the past 20 years to 2020. The state has criminal codes for hooning, graffiti, sharing intimate images without consent and fare evasion. Wage theft became a crime in 2020. The minimum age of criminal responsibility in Queensland is 10 years old.

Love v Commonwealth; Thoms v Commonwealth is a High Court of Australia case that held that Aboriginal Australians could not be classified as aliens under section 51(xix) of the Australian Constitution. The case was decided on 11 February 2020.

Jacinta Yangapi Nampijinpa Price is an Australian politician from the Northern Territory. She has been a senator for the Northern Territory since the 2022 federal election. She is a member of the Country Liberal Party, a politically conservative party operating in the Northern Territory affiliated with the national Coalition. She sits with the National Party in federal parliament. She has been the Shadow Minister for Indigenous Affairs since April 2023.

References

- ↑ Australian Institute of Criminology, The age of criminal responsibility, September 2005 (Canberra).

- ↑ R v CRH (Unreported, NSW Court of Criminal Appeal, Smart, Hidden and Newman JJ, 18 December 1996); C (A Minor) v DPP [1995] 2 WLR 383, 401-2; BP v R, SW v R [2006] NSWCCA 172 (1 June 2006).

- 1 2 "Experts back call to raise age of criminal responsibility to 16". SBS Australia. 22 November 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Creek, Simon; Nims, Siobhan (30 July 2020). "Quick Facts: The age of criminal responsibility in Australia and youth incarceration". Welcome to Mondaq. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- 1 2 "Review of the age of criminal responsibility (2020)". Australian Human Rights Commission. 26 February 2020. Retrieved 6 August 2020. PDF

- 1 2 "Council of Attorneys-General – Age of Criminal Responsibility Working Group Review". Law Council of Australia. 29 July 2020. Retrieved 6 August 2020. PDF

- ↑ "AMA calls for age of criminal responsibility to be raised to 14 years of age". Australian Medical Association. 25 March 2019. Retrieved 12 April 2019.

- 1 2 Zwartz, Henry; Dunstan, Joseph (26 July 2020). "The push to raise Australia's minimum age of criminal responsibility". ABC News. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- 1 2 Cunneen, Chris (22 July 2020). "Ten-year-olds do not belong in detention. Why Australia must raise the age of criminal responsibility". The Conversation. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ↑ "age of criminal responsibility". RACP. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ↑ Ralston, Nick; Whitbourn, Michaela (27 July 2020). "Age of criminal responsibility to remain at 10 until at least 2021". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ↑ Richards, Stephanie (28 July 2020). "Move to lift criminal age on hold as SA waits for national decision". InDaily. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- 1 2 Richards, Stephanie (4 July 2022). "Greens push to lift SA's criminal age from 10". InDaily . Retrieved 13 October 2022.

- ↑ Goldsworthy, Terry (1 September 2022). "Why we should not rush to raise the age of criminal responsibility in Australia". The Conversation . Retrieved 13 October 2022.

- 1 2 3 Holland, Lorelle; Toombs, Maree (2 August 2022). "Raising the age of criminal responsibility is only a first step. First Nations kids need cultural solutions". The Conversation . Retrieved 13 October 2022.

- ↑ Keoghan, Sarah; Whitbourn, Michaela (26 July 2020). "Council of Attorney's-General to urge change of age for criminal responsibility". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ↑ National Agreement on Closing the Gap (PDF), July 2020, retrieved 4 August 2020

- ↑ York, Keva (20 February 2020). "In My Blood It Runs documentary exposes how education system is failing Aboriginal children". ABC News. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ↑ Knowles, Rachael (5 October 2021). "WA Labor passes motion to raise the age". National Indigenous Times . Retrieved 13 October 2022.

- ↑ Dennien, Matt (15 March 2022). "Bill to raise age of criminal responsibility to 14 in Qld rejected by committee". Brisbane Times . Retrieved 13 October 2022.

- ↑ MacDonald, Lucy (8 June 2022). "Tasmania set to be first jurisdiction to raise minimum age of children in youth detention". ABC News. Retrieved 13 October 2022.

- ↑ Morgan, Thomas (13 October 2022). "NT government to introduce laws raising the age of criminal responsibility and reforming adult mandatory sentencing". ABC News. Retrieved 13 October 2022.

- ↑ "Why Australia is facing calls to stop jailing 10-year-olds". BBC News. 21 August 2020. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ↑ Allam, Lorena (20 August 2020). "Australian Capital Territory votes to raise age of criminal responsibility from 10 to 14". the Guardian. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ↑ "Criminal responsibility age to be raised from 10 to 14 if ACT Labor re-elected, after Government endorses reform - ABC News". ABC (Australian Broadcasting Corporation). 20 August 2020. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ↑ Jenkins, Keira (20 August 2020). "ACT agrees to raise age of criminal responsibility". NITV. Retrieved 23 August 2020.

- ↑ "ACT raises the age of criminal responsibility to 14 with nation-first legislation". ABC News. 1 November 2023. Retrieved 12 May 2024.

- 1 2 "Justice (Age of Criminal Responsibility) Legislation Amendment Act 2023". ACT Legislative Assembly . Retrieved 12 May 2024.

- ↑ "Crimes Act 1900". ACT Legislative Assembly . Retrieved 12 May 2024.

- ↑ "Acts of Indecency". Armstrong Legal. Retrieved 12 May 2024.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 March 2012. Retrieved 12 October 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - 1 2 Criminal Code Act 1995 (series)

- ↑ "NT sets date for changing age of criminal responsibility, but advocates call for more changes". ABC News. 24 July 2023. Retrieved 12 October 2023.

- ↑ "WALW - Criminal Code Act Compilation Act 1913 - Home Page". www.legislation.wa.gov.au.