A dune is a landform composed of wind- or water-driven sand. It typically takes the form of a mound, ridge, or hill. An area with dunes is called a dune system or a dune complex. A large dune complex is called a dune field, while broad, flat regions covered with wind-swept sand or dunes with little or no vegetation are called ergs or sand seas. Dunes occur in different shapes and sizes, but most kinds of dunes are longer on the stoss (upflow) side, where the sand is pushed up the dune, and have a shorter slip face in the lee side. The valley or trough between dunes is called a dune slack.

Ammophila is a genus of flowering plants consisting of two or three very similar species of grasses. The common names for these grasses include marram grass, bent grass, and beachgrass. These grasses are found almost exclusively on the first line of coastal sand dunes. Their extensive systems of creeping underground stems or rhizomes allow them to thrive under conditions of shifting sands and high winds, and to help stabilize and prevent coastal erosion. Ammophila species are native to the coasts of the North Atlantic Ocean where they are usually the dominant species on sand dunes. Their native range includes few inland regions, with the Great Lakes of North America being the main exception. The genus name Ammophila originates from the Greek words ἄμμος (ámmos), meaning "sand", and φίλος (philos), meaning "friend".

The Oregon Dunes National Recreation Area is located on the Oregon Coast, stretching approximately 40 miles (64 km) north of the Coos River in North Bend to the Siuslaw River in Florence, and adjoining Honeyman State Park on the west. It is part of Siuslaw National Forest and is administered by the United States Forest Service.

Grey dunes are fixed, stable sand dunes that are covered by a continuous layer of herbaceous vegetation. These dunes are typically located 50–100 meters from the ocean shore and are found on the landward side of foredunes. Grey dunes are named for their characteristic grey color which is a result of the ground cover of lichen combined with a top soil layer of humus.

NVC community SD11 is one of the 16 sand-dune communities in the British National Vegetation Classification system.

Uniola paniculata, also known as sea oats, seaside oats, araña, and arroz de costa, is a tall subtropical grass that is an important component of coastal sand dune and beach plant communities in the southeastern United States, eastern Mexico and some Caribbean islands.

Ammophila arenaria is a species of grass in the family Poaceae. It is known by the common names marram grass and European beachgrass. It is one of two species of the genus Ammophila. It is native to the coastlines of Europe and North Africa where it grows in the sands of beach dunes. It is a perennial grass forming stiff, hardy clumps of erect stems up to 1.2 metres (3.9 ft) in height. It grows from a network of thick rhizomes which give it a sturdy anchor in its sand substrate and allow it to spread upward as sand accumulates. These rhizomes can grow laterally by 2 metres in six months. One clump can produce 100 new shoots annually.

The New River is a stream, about 8 miles (13 km) long, on the southern coast of the U.S. state of Oregon. It begins slightly north of Floras Lake, at the confluence of the lake outlet and Floras Creek, and runs north behind a foredune until entering the Pacific Ocean between Bandon and Port Orford.

Sand dune ecology describes the biological and physico-chemical interactions that are a characteristic of sand dunes.

The Lanphere Dunes National Natural Landmark a unit of the Humboldt Bay National Wildlife Refuge Complex, is located in Humboldt County, California. The dune complex consists of the wave slope, fore dune, herbaceous and woody swales, coniferous and riparian forest, freshwater swamp, freshwater marsh, brackish marsh, salt marsh, and intertidal mudflats. The site exemplifies dunes succession.

NVC community SD19 is one of the 16 sand-dune communities in the British National Vegetation Classification system. It is one of six communities associated with foredunes and mobile dunes.

Sand dune stabilization is a coastal management practice designed to prevent erosion of sand dunes. Sand dunes are common features of shoreline and desert environments. Dunes provide habitat for highly specialized plants and animals, including rare and endangered species. They can protect beaches from erosion and recruit sand to eroded beaches. Dunes are threatened by human activity, both intentional and unintentional. Countries such as the United States, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and Netherlands, operate significant dune protection programs.

Clatsop Spit is a giant sand spit on the Pacific coast along U.S. Route 101 between Astoria and the north end of Tillamook Head in Clatsop County, northwest Oregon at the mouth of the Columbia River. The Clatsop Spit was formed by Columbia River sediment brought to the coast by the river flow after the last ice age ended approximately 8500 years ago and the ocean level rose. Here it was worked over and shaped by the wind and the waves until a vast and sandy plain was formed. In regular conversation, referring to Clatsop Spit usually refers to the northern end of the spit: The area that is bound by the Pacific to the west and the Columbia River to the northeast. In the past, the spit was known as Clatsop Sands.

Phacelia argentea is a rare species of phacelia known by the common names sand dune phacelia and silvery phacelia. It is native to the coastline of southwestern Oregon and far northwestern California, where it was counted at a total of 33 sites in 1995. It is the only phacelia species endemic to coastal sand dune habitat, an ecosystem which is altered and declining in the area.

A foredune is a dune ridge that runs parallel to the shore of an ocean, lake, bay, or estuary. Foredunes consist of sand deposited by wind on a vegetated part of the shore. Foredunes can be classified generally as incipient or established.

Leymus mollis is a species of grass known by the common names American dune grass, American dune wild-rye, sea lyme-grass, strand-wheat, and strand grass. Its Japanese name is hamaninniku. It is native to Asia, where it occurs in Japan, China, Korea, and Russia, and northern parts of North America, where it occurs across Canada and the northern United States, as well as Greenland. It can also be found in Iceland.

The Ma-le’l Dunes Cooperative Management Area (CMA) is located south of Lanphere Dunes at the upper end of the North Spit of Humboldt Bay, being approximately one mile north of the unincorporated town of Manila and 3.5 miles west of the City of Arcata, in Humboldt County, California. It consists of approximately 444 acres of public land. Ma-le’l dunes are divided into northern and southern sections. The northern portion is part of Humboldt Bay National Wildlife Refuge and is administered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS). The southern portion of Ma-le’l is managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and provides access to the coastal dune environment for dog-walking and equestrian use on designated trails.

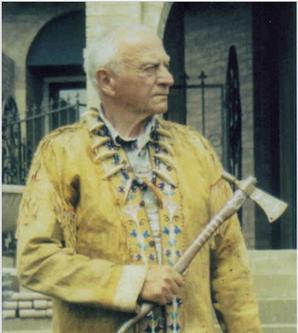

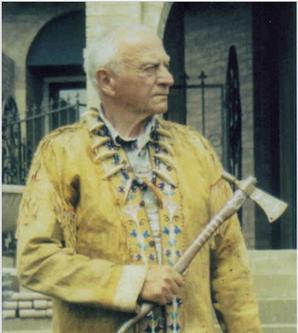

Wilbur E. Ternyik was an American civic leader who has been characterized as a founding father of coastal planning, a coastal advocate, and a guardian of the Oregon Coast. News coverage of his work has described him as an international expert on sand dunes, and has noted his "decades of work to protect the environment that draws thousands to the Oregon coast." Ternyik's outreach to skeptical local officials in the early 1970s, persuading them to engage with then-Governor Tom McCall's call for land use planning in advance of the state's landmark land use legislation, has been identified as his most significant achievement.

Dynamic revetment, also known as a "cobble berm", uses gravel or cobble-sized rocks to mimic a natural cobble storm beach for the purpose of reducing wave energy and stopping or slowing coastal erosion. Unlike seawalls, dynamic revetment is designed to allow wave action to rearrange the stones into an equilibrium profile, disrupting wave action and dissipating wave energy as the cobbles move. This can reduce the wave reflection which often contributes to beach scouring.