Related Research Articles

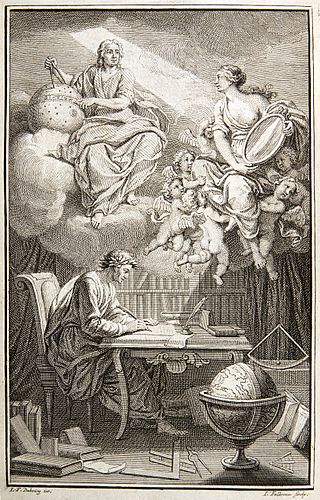

François-Marie Arouet, known by his nom de plumeM. de Voltaire, was a French Enlightenment writer, philosopher (philosophe), satirist, and historian. Famous for his wit and his criticism of Christianity and of slavery, Voltaire was an advocate of freedom of speech, freedom of religion, and separation of church and state.

Hippolyte Adolphe Taine was a French historian, critic and philosopher. He was the chief theoretical influence on French naturalism, a major proponent of sociological positivism and one of the first practitioners of historicist criticism. Literary historicism as a critical movement has been said to originate with him. Taine is also remembered for his attempts to provide a scientific account of literature.

Joseph Marie, comte de Maistre was a Savoyard philosopher, lawyer, diplomat, and magistrate. One of the forefathers of conservatism, Maistre advocated social hierarchy and monarchy in the period immediately following the French Revolution. Despite his close personal and intellectual ties with France, Maistre was throughout his life a subject of the Kingdom of Sardinia, which he served as a member of the Savoy Senate (1787–1792), ambassador to Russia (1803–1817), and minister of state to the court in Turin (1817–1821).

Charles Augustin Sainte-Beuve was a French literary critic.

Jean-François de La Harpe was a French playwright, writer and literary critic.

Pierre Maurice Marie Duhem was a French theoretical physicist who worked on thermodynamics, hydrodynamics, and the theory of elasticity. Duhem was also a historian of science, noted for his work on the European Middle Ages, which is regarded as having created the field of the history of medieval science. As a philosopher of science, he is remembered principally for his views on the indeterminacy of experimental criteria.

The Counter-Enlightenment refers to a loose collection of intellectual stances that arose during the European Enlightenment in opposition to its mainstream attitudes and ideals. The Counter-Enlightenment is generally seen to have continued from the 18th century into the early 19th century, especially with the rise of Romanticism. Its thinkers did not necessarily agree to a set of counter-doctrines but instead each challenged specific elements of Enlightenment thinking, such as the belief in progress, the rationality of all humans, liberal democracy, and the increasing secularisation of society.

Jean Guitton was a French Catholic philosopher and theologian. Le Monde called him "the last of the great Catholic philosophers."

Henri de Boulainvilliers was a French nobleman, writer and historian. He was educated at the College of Juilly; he served in the army until 1697.

Philipp Albert Stapfer was a Swiss politician and philosopher.

The Lumières was a cultural, philosophical, literary and intellectual movement beginning in the second half of the 17th century, originating in western Europe and spreading throughout the rest of Europe. It included philosophers such as Baruch Spinoza, David Hume, John Locke, Edward Gibbon, Voltaire, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Denis Diderot, Pierre Bayle and Isaac Newton. This movement is influenced by the scientific revolution in southern Europe arising directly from the Italian Renaissance with people like Galileo Galilei. Over time it came to mean the Siècle des Lumières, in English the Age of Enlightenment.

The following events related to sociology occurred in the 1840s.

Hyacinthe de Valroger, CO, was a French Catholic priest and Oratorian.

François Poullain de la Barre was an author, Catholic priest, and a Cartesian philosopher.

Traditionalism, in the context of 19th-century Catholicism, refers to a theory which held that all metaphysical, moral, and religious knowledge derives from God's revelation to man and is handed down in an unbroken chain of tradition. It denied that human reason by itself has the power to attain to any truths in these domains of knowledge. It arose, mainly in Belgium and France, as a reaction to 18th-century rationalism and can be considered an extreme form of anti-rationalism.

The Prix Sainte-Beuve, established in 1946, is a French literary prize awarded each year to a writer in the categories "novels" and "essays" ; it is named after the writer Charles-Augustin Sainte-Beuve. The founding jury included Raymond Aron, Maurice Blanchot, Edmond Buchet, Maurice Nadeau, Jean Paulhan and Raymond Queneau.

Michel Crépu is a French writer and literary critic as well as the editor-in-chief of Nouvelle Revue française since 2015.

Stéphane Van Damme is historian and Professor of Early Modern History at the École normale supérieure in Paris, France.

Graeme Garrard is a Canadian political theorist and writer. He is Professor of Politics at Cardiff University in the UK.

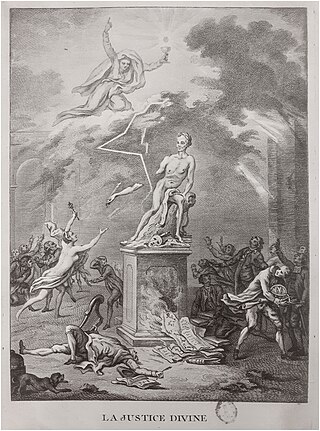

Considerations on France is a 1796 political pamphlet and treatise by the Savoyard philosopher Joseph de Maistre about the ongoing French Revolution. Maistre presents a providential interpretation of the Revolution and argues for a new alliance of throne and altar under a restored Bourbon monarchy. The work is the best-known French equivalent of Edmund Burke's work Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790).

References

- ↑ Huet, François (1837). "Le Chancelier Bacon et le Comte Joseph de Maistre." In: Nouvelles Archives Historiques, Philosophiques et Littéraires. Gand: C. Annoot-Braekman, vol. I, pp. 65–94.

- ↑ Gourmont, Rémy de (1905). "François Bacon et Joseph de Maistre." In: Promenades Philosophiques. Paris: Mercure de France, pp. 7–32.

- ↑ Richard A., Lebrun (1998). "Introduction". In de Maistre, Joseph (ed.). An Examination of the Philosophy of Bacon. McGill's Queen's University Press. pp. xxi–xxii. ISBN 0-7735-1727-8.

- ↑ Reardon, Bernard (2010). Liberalism and Tradition. Cambridge University Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-521-14305-9. OCLC 502414345.

- ↑ Bonnetty, Augustin (31 July 1836). Annales de Philosophic Chretiennes. 13 (73).

{{cite journal}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ↑ Sainte-Beuve, Charles Augustin (1843). Revue des Deux Mondes. p. 387.

- ↑ Richard A., Lebrun (1998). "Introduction". In de Maistre, Joseph (ed.). An Examination of the Philosophy of Bacon. McGill's Queen's University Press. pp. xxiv–xxv. ISBN 0-7735-1727-8.

- ↑ Siedentop, Larry (1966). The Limits of Enlightenment. p. 348.

- ↑ Bradley, Owen (1992). Logics of Violence: The Social and Political Thought of Joseph de Maistre. Cornell University. p. 453.