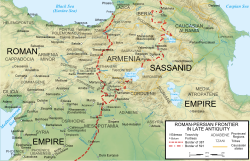

Kavad's campaign of 502

In 502, Kavad quickly captured the unprepared city of Theodosiopolis, perhaps with local support; the city was in any case undefended by troops and weakly fortified. [3] Martyropolis also fell in the same year. Kavad then besieged the fortress-city of Amida through the autumn and winter (502-503) and captured it after a lengthy siege, although the defenders were unsupported by troops. [4] Many people, particularly the population of Amida, were deported to Pars and Khuzestan in Persia, in particular, to the new city of Veh-az-Amid Kavad (Arrajan). [5]

Anastasius' campaign of 503 and Kavad's counterattack

The Byzantine emperor Anastasius I dispatched an army in May 503 against the Sasanians. The army numbered 52,000 men, the largest Roman force in the East since Julian's invasion of Persia, and the largest assembled Roman army throughout the 6th century. [6] The force gathered at Edessa and Samosata. It operated in three divisions under magister militum per Orientem Areobindus, strategos Patricius, and Hypatius. Hypatius and Patricius attacked Amida, which was held by a 3,000-strong garrison under Glones. Areobindus, together with Romanus and the Arab phylarch Asouades (Aswad) (probably a Kinda leader) attacked Nisibis, in which Kavad was residing. [7] [8] Procopius also mentions Celer as a fourth commander. [9] Notable officers associated with this force include "hyparch" Apion I (the Egyptian), [10] comes Justin (the future emperor), [11] Patriciolus and his son Vitalian (who later revolted against Anastasius), the Colchian Pharesmanes, and the Goths Godidisklus and Bessas. [9]

Initially, Areobindus gained the upper hand in Nisibis, but Kavad's counterattack defeated him, plundered his fort Apadna, and forced him to retreat westward; Hypatius and Patricius attempted to assist him, but it was too late. [7] They failed to join with Areobindus and were decisively defeated between Apadna and Tell Beshme and retreated to Samosata. According to Zacharias, their cavalry suffered heavily during the retreat, falling from the cliffs of mountains. Kavad continued westward to Constantia but failed to capture it, though he received supplies from its inhabitants. In early September, Kavad reached near Edessa. Areobindus rejected Kavad's demand of 10,000 pounds (4,500 kg) of gold in exchange for peace. Sasanians and Lakhmids overran much of Osrhoene but attempts to attack the fortified city failed. Meanwhile, Byzantine forces under Pharesmanes attacked Amida, who killed the Sasanian commander Glones through cunning. This, together with Hunnic incursions, the arrival of Byzantine reinforcements, and Kavad's lack of supplies, all forced him to withdraw to Persia. This further contributed to the reputation of Edessa as being impregnable. [11] [12] Meanwhile, the dux of Osrhoene, Timostratus, defeated the Lakhmids, and the Tha'labites (Byzantine Arabs) attacked Lakhmid capital al-Hira. [11]

Anastasius' renewed assault

In the summer of 503, Anastasius sent reinforcements under magister officiorum Celer and canceled taxes from Mesopotamia and Osrhoene, while Hypatius and Apion were recalled. Patricius moved to Amida, defeated a force sent against him, and invested the city; Celer joined him later in the spring of 504. While the siege was ongoing, Celer raided Beth Arabaye, while Areobindus raided Arzanene. Sasanian weakness at this point is apparent by defections to the Byzantine side by the renegade Constantine, a certain Arab chief Adid, and the Armenian Mushlek. The Byzantines eventually captured Amida. [13] [11]

Peace treaty

In the same year, an armistice was agreed as a result of an invasion of Armenia by the Huns from the Caucasus. Negotiations between the two powers took place, but such was the distrust that in 506 the Romans, suspecting treachery, seized the Persian officials; once released, the Persians preferred to stay in Nisibis. [13] In November 506, a treaty was finally agreed, but little is known of what the terms of the treaty were. Procopius states that peace was agreed for seven years, and it is likely that some payments were made to the Persians. [14] The Persians did not keep Byzantine territory and no annual tribute was paid so it seems the peace treaty was not harsh on the Byzantines. [15]