Empúries was an ancient city on the Mediterranean coast of Catalonia, Spain. Empúries is also known by its Spanish name, Ampurias. The city Ἐμπόριον was founded in 575 BC by Greek colonists from Phocaea. After the invasion of Gaul from Iberia by Hannibal the Carthaginian general in 218 BC, the city was occupied by the Romans. In the Early Middle Ages, the city's exposed coastal position left it open to marauders and it was abandoned.

The Iberians were an ancient people settled in the eastern and southern coasts of the Iberian peninsula, at least from the 6th century BC. They are described in Greek and Roman sources. Roman sources also use the term Hispani to refer to the Iberians.

The Iberian language was the language of an indigenous western European people identified by Greek and Roman sources who lived in the eastern and southeastern regions of the Iberian Peninsula in the pre-Migration Era. An ancient Iberian culture can be identified as existing between the 7th and 1st centuries BC, at least.

The Celtiberian script is a Paleohispanic script that was the main writing system of the Celtiberian language, an extinct Continental Celtic language, which was also occasionally written using the Latin alphabet. This script is a direct adaptation of the northeastern Iberian script, the most frequently used of the Iberian scripts.

The Vettones were an Iron Age pre-Roman people of the Iberian Peninsula of possibly Celtic ethnicity.

The falcata is a type of sword typical of pre-Roman Iberia. The falcata was used to great effect for warfare in the ancient Iberian peninsula, and is firmly associated with the southern Iberian tribes, among other ancient peoples of Hispania. It was highly prized by the ancient general Hannibal, who equipped Carthaginian troops with it during the Second Punic War.

Tartessian is an extinct Paleo-Hispanic language found in the Southwestern inscriptions of the Iberian Peninsula, mainly located in the south of Portugal, and the southwest of Spain. There are 95 such inscriptions, the longest having 82 readable signs. Around one third of them were found in Early Iron Age necropolises or other Iron Age burial sites associated with rich complex burials. It is usual to date them to the 7th century BC and to consider the southwestern script to be the most ancient Paleo-Hispanic script, with characters most closely resembling specific Phoenician letter forms found in inscriptions dated to c. 825 BC. Five of the inscriptions occur on stelae with what has been interpreted as Late Bronze Age carved warrior gear from the Urnfield culture.

The Lusones were an ancient Celtiberian (Pre-Roman) people of the Iberian Peninsula, who lived in the high Tajuña River valley, northeast of Guadalajara. They were eliminated by the Romans as a significant threat in the end of the 2nd century BC.

Sagunto is a municipality of Spain, located in the province of Valencia, Valencian Community. It belongs to the modern fertile comarca of Camp de Morvedre. It is located c. 30 km north of the city of Valencia, close to the Costa del Azahar on the Mediterranean Sea.

The Carpetani were one of the Celtic pre-Roman peoples of the Iberian Peninsula, akin to the Celtiberians, dwelling in the central part of the meseta - the high central upland plain of the Iberian Peninsula.

The Espanca script is the first signary known of the Paleohispanic scripts. It is inscribed on a piece of slate, 48×28×2 cm. This alphabet consists of 27 letters written double. The 27 letters in the outer line are written in a better hand than those of the inner line, from which it has been inferred that the slate was a teaching exercise in which a master wrote the alphabet and a student copied it.

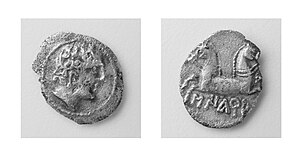

Joaquín Rubio y Muñoz was a Spanish lawyer who was a noted antiquarian and numismatist in the city of Cádiz, Spain. He built up a library of manuscripts and rare books and in particular was known for his extensive collection of ancient coins and medals, many of which are now in museums in Spain and Denmark.

Hispania was the Roman name for the Iberian Peninsula and its provinces. Under the Roman Republic, Hispania was divided into two provinces: Hispania Citerior and Hispania Ulterior. During the Principate, Hispania Ulterior was divided into two new provinces, Baetica and Lusitania, while Hispania Citerior was renamed Hispania Tarraconensis. Subsequently, the western part of Tarraconensis was split off, first as Hispania Nova, later renamed "Callaecia". From Diocletian's Tetrarchy onwards, the south of the remainder of Tarraconensis was again split off as Carthaginensis, and all of the mainland Hispanic provinces, along with the Balearic Islands and the North African province of Mauretania Tingitana, were later grouped into a civil diocese headed by a vicarius. The name Hispania was also used in the period of Visigothic rule.

The economy of Hispania, or Roman Iberia, experienced a strong revolution during and after the conquest of the peninsular territory by Rome, in such a way that, from an unknown but promising land, it came to be one of the most valuable acquisitions of both the Republic and Empire and a basic pillar that sustained the rise of Rome.

Urci was an ancient settlement in southeastern Roman Hispania mentioned by Pomponius Mela, Pliny the Elder, and Claudius Ptolemy. The writings of these historians indicate that the city was located in the hinterland of what is now Villaricos, Spain, in the lower basin of the Almanzora River. Some modern encyclopedias and historians have wrongly located Urci at Pechina, El Chuche or the City of Almería.

The Lobetani, were a small pre-Roman Iberian people of ancient Spain mentioned only once by Ptolemy in the 2nd century AD, situated around the mountainous Albarracín area of the southwest Province of Teruel.

The Olcades were an ancient stock-raising pre-Roman people from Hispania, who lived to the west of the Turboletae in the southeastern fringe of the Iberian system mountains.

The coinage of the Visigoths was minted in Gaul and Hispania during the early Middle Ages, between the fifth century and approximately 710.

Kelin was an ancient Iberian city located on the hill of Los Villares. The site was inhabited from the Proto-Iberian period to the Late Iberian period. The site was walled and covered around 10 hectares. The archaeological site has been known from the mid-18th century, although it was first excavated archaeologically in 1956, with later campaigns as recent as 2011.

Hispania is the national personification of Spain.