Related Research Articles

Czesław Miłosz was a Polish-American poet, prose writer, translator, and diplomat. He primarily wrote his poetry in Polish. Regarded as one of the great poets of the 20th century, he won the 1980 Nobel Prize in Literature. In its citation, the Swedish Academy called Miłosz a writer who "voices man's exposed condition in a world of severe conflicts".

A cartoon is a type of visual art that is typically drawn, frequently animated, in an unrealistic or semi-realistic style. The specific meaning has evolved, but the modern usage usually refers to either: an image or series of images intended for satire, caricature, or humor; or a motion picture that relies on a sequence of illustrations for its animation. Someone who creates cartoons in the first sense is called a cartoonist, and in the second sense they are usually called an animator.

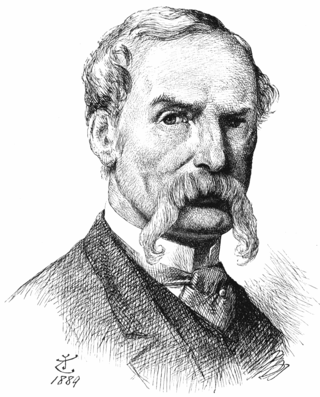

Sir John Tenniel was an English illustrator, graphic humourist and political cartoonist prominent in the second half of the 19th century. An alumnus of the Royal Academy of Arts in London, he was knighted for artistic achievements in 1893, the first such honour ever bestowed on an illustrator or cartoonist.

Sir David Alexander Cecil Low was a New Zealand political cartoonist and caricaturist who lived and worked in the United Kingdom for many years. Low was a self-taught cartoonist. Born in New Zealand, he worked in his native country before migrating to Sydney in 1911, and ultimately to London (1919), where he made his career and earned fame for his Colonel Blimp depictions and his satirising of the personalities and policies of German dictator Adolf Hitler, Italian dictator Benito Mussolini, Soviet leader Joseph Stalin, and other leaders of his times.

A cartoonist is a visual artist who specializes in both drawing and writing cartoons or comics. Cartoonists differ from comics writers or comics illustrators/artists in that they produce both the literary and graphic components of the work as part of their practice.

A political cartoon, also known as an editorial cartoon, is a cartoon graphic with caricatures of public figures, expressing the artist's opinion. An artist who writes and draws such images is known as an editorial cartoonist. They typically combine artistic skill, hyperbole and satire in order to either question authority or draw attention to corruption, political violence and other social ills.

Gerald Anthony Scarfe is an English cartoonist and illustrator. He has worked as editorial cartoonist for The Sunday Times and illustrator for The New Yorker.

Edward Sorel is an American illustrator, caricaturist, cartoonist, graphic designer and author. His work is known for its storytelling, its left-liberal social commentary, its criticism of reactionary right-wing politics and organized religion. Formerly a regular contributor to The Nation, New York Magazine and The Atlantic, his work is today seen more frequently in Vanity Fair. He has been hailed by The New York Times as "one of America's foremost political satirists". As a lifelong New Yorker, a large portion of his work interprets the life, culture and political events of New York City. There is also a large body of work which is nostalgic for the stars of 1930s and 1940s Hollywood when Sorel was a youth. Sorel is noted for his wavy pen-and-ink style, which he describes as "spontaneous direct drawing".

Edward Linley Sambourne was an English cartoonist and illustrator most famous for being a draughtsman for the satirical magazine Punch for more than forty years and rising to the position of "First Cartoonist" in his final decade. He was also a great-grandfather of Antony Armstrong-Jones, 1st Earl of Snowdon, who was the husband of Princess Margaret.

Tom Richmond is an American freelance humorous illustrator, cartoonist and caricaturist whose work has appeared in many national and international publications since 1990. He was chosen as the 2011 "Outstanding Cartoonist of the Year", also known as "The Reuben Award", winner by the National Cartoonists Society.

Peter Whalley was a Canadian caricaturist, cartoonist, illustrator and sculptor.

Jim Bamber was a British artist and editorial cartoonist specialising in motorsport, who is best known for his motor racing related caricatures which incorporate his distinctive driver designs, that adorned every issue of Autosport magazine as well as his annual compilation of cartoons from the magazine called The Pits.

Jerzy Zaruba (1891–1971) was a Polish graphic artist, stage scenographer and caricaturist; author of satirical drawings, political crèches and illustrations for books and magazines. Pupil of Stanisław Lentz. His work was part of the painting event in the art competition at the 1928 Summer Olympics.

Andrzej Szczypiorski was a Polish novelist and politician. He served as a member of the Polish legislature, and was a Solidarity activist interned during the military crackdown of 1981. He was a secret police agent in the 1950s.

Kazimierz Brandys was a Polish essayist and writer of film scripts.

Museum of Caricature is a museum in Warsaw, Poland. The museum was founded by Eryk Lipiński in 1978, and he was the director of the museum until his death in 1991. The museum has a collection of over 20,000 pieces by Polish and foreign artists.

David Alan Parkins is a British cartoonist and illustrator who has worked for D.C. Thomson, publisher of The Beano and The Dandy. Now based in Canada, he illustrates children's picture books.

Irena Krzywicka née Goldberg was a Polish feminist, writer, translator and activist for women's rights, who promoted sexual education, contraception and planned parenthood.

Antoni Krauze was a Polish screenwriter and director.

Tomasz Samojlik is a scientist, a biologist and an environmental historian. In his research he focuses mainly on the history of fires and their role in shaping the Białowieża Primeval Forest's environment, the role of livestock grazing in modifying woodlands of the Białowieża Forest in the last five centuries, and the environmental history of the Białowieża Forest in the 19th and 20th centuries.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Andrzej Krauze". British Cartoon Archive . Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Stephen Moss (17 October 2001). "Spitting images". The Guardian . Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Francis Wheen (8 March 2003). "Master of his art". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- 1 2 Patrick Wright (17 November 2007). "Andrzej Krauze comes to London" (PDF). PatrickWright.net. Retrieved 24 February 2013.

- 1 2 "UN award for cartoonist". The Guardian. 18 November 2003. Retrieved 2 March 2013.

- ↑ "Andrzej Krauze 'Trzy Dekady'" [Andrzej Krauze 'Three Decades'] (in Polish). Biuro Wystaw Artystycznych w Jeleniej Górze. Archived from the original on 11 April 2013. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

- ↑ Krauze, Andrzej (2010). The Sleep of Reason... Drawings 1970–1989. Instytut Pamięci Narodowej. p. 4. ISBN 978-83-7629-129-1.

A DVD version of a film entitled The Flying Lesson (1973, dir. Andrzej Krauze) from the Studio Miniatur Filmowych is attached

- ↑ Krauze (2010). The Sleep of Reason... Drawings 1970–1989. p. 73. ISBN 9788376291291.

On 14 August 1979, I left Poland ... After a month spent in Paris we headed for London. ... After a year, however, the Home Office re-fused to extend our visas and we were obliged to leave England.

- ↑ Krauze (2010). The Sleep of Reason... Drawings 1970–1989. p. 73. ISBN 9788376291291.

in January 1981 returned to Paris.

- ↑ Moss, Stephen (17 October 2001). "Andrzej Krauze's emotional homecoming". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077 . Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- ↑ "Andrzej Krauze – 15 lat z 'Rzeczpospolitą'". Logo RP (in Polish). Retrieved 15 April 2019.

- ↑ "Wystawa Andrzeja Krauzego "Drzewa" Tygodnik Sieci". www.wsieciprawdy.pl. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- ↑ "Andrzej i Antoni Krauze odebrali Nagrodę im. Lecha Kaczyńskiego". www.tvp.info (in Polish). 20 May 2017. Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- ↑ "Kaczyński wręczył Antoniemu Krauze i Andrzejowi Krauze nagrodę im. L. Kaczyńskiego". Newsweek.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 7 January 2019.

- ↑ Andrzej Krauze ze Złotym Medalem "Gloria Artis" MKiDN - 2017 (in Polish), retrieved 7 January 2019

- ↑ "Baudelaire, a Lucca Libri si presentano i 'Quadri parigini'" [Baudelaire, the 'Parisian paintings' are presented at Lucca Libri]. Lucca in Diretta (in Italian). 13 December 2017. Retrieved 15 April 2019.

- ↑ Alan Rusbridger. "Andrzej Krauze: Drawings 1970–2003". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 March 2013.