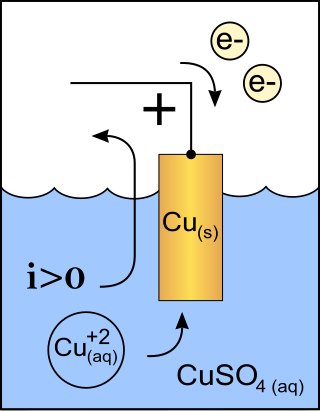

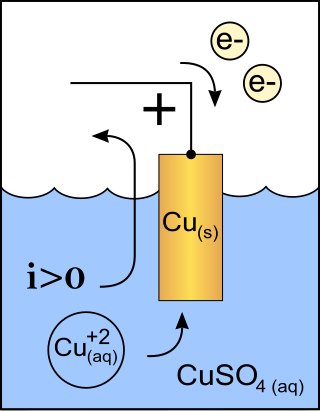

An anode is an electrode of a polarized electrical device through which conventional current enters the device. This contrasts with a cathode, an electrode of the device through which conventional current leaves the device. A common mnemonic is ACID, for "anode current into device". The direction of conventional current in a circuit is opposite to the direction of electron flow, so electrons flow out the anode of a galvanic cell, into an outside or external circuit connected to the cell. For example, the end of a household battery marked with a "-" (minus) is the anode.

An electric current is a flow of charged particles, such as electrons or ions, moving through an electrical conductor or space. It is defined as the net rate of flow of electric charge through a surface. The moving particles are called charge carriers, which may be one of several types of particles, depending on the conductor. In electric circuits the charge carriers are often electrons moving through a wire. In semiconductors they can be electrons or holes. In an electrolyte the charge carriers are ions, while in plasma, an ionized gas, they are ions and electrons.

Cathode rays or electron beam (e-beam) are streams of electrons observed in discharge tubes. If an evacuated glass tube is equipped with two electrodes and a voltage is applied, glass behind the positive electrode is observed to glow, due to electrons emitted from the cathode. They were first observed in 1859 by German physicist Julius Plücker and Johann Wilhelm Hittorf, and were named in 1876 by Eugen Goldstein Kathodenstrahlen, or cathode rays. In 1897, British physicist J. J. Thomson showed that cathode rays were composed of a previously unknown negatively charged particle, which was later named the electron. Cathode-ray tubes (CRTs) use a focused beam of electrons deflected by electric or magnetic fields to render an image on a screen.

A cathode is the electrode from which a conventional current leaves a polarized electrical device. This definition can be recalled by using the mnemonic CCD for Cathode Current Departs. A conventional current describes the direction in which positive charges move. Electrons have a negative electrical charge, so the movement of electrons is opposite to that of the conventional current flow. Consequently, the mnemonic cathode current departs also means that electrons flow into the device's cathode from the external circuit. For example, the end of a household battery marked with a + (plus) is the cathode.

The electron is a subatomic particle with a negative one elementary electric charge. Electrons belong to the first generation of the lepton particle family, and are generally thought to be elementary particles because they have no known components or substructure. The electron's mass is approximately 1/1836 that of the proton. Quantum mechanical properties of the electron include an intrinsic angular momentum (spin) of a half-integer value, expressed in units of the reduced Planck constant, ħ. Being fermions, no two electrons can occupy the same quantum state, per the Pauli exclusion principle. Like all elementary particles, electrons exhibit properties of both particles and waves: They can collide with other particles and can be diffracted like light. The wave properties of electrons are easier to observe with experiments than those of other particles like neutrons and protons because electrons have a lower mass and hence a longer de Broglie wavelength for a given energy.

Sir Joseph John Thomson was a British physicist and Nobel Laureate in Physics, credited with the discovery of the electron, the first subatomic particle to be found.

The Geiger–Müller tube or G–M tube is the sensing element of the Geiger counter instrument used for the detection of ionizing radiation. It is named after Hans Geiger, who invented the principle in 1908, and Walther Müller, who collaborated with Geiger in developing the technique further in 1928 to produce a practical tube that could detect a number of different radiation types.

A cold cathode is a cathode that is not electrically heated by a filament. A cathode may be considered "cold" if it emits more electrons than can be supplied by thermionic emission alone. It is used in gas-discharge lamps, such as neon lamps, discharge tubes, and some types of vacuum tube. The other type of cathode is a hot cathode, which is heated by electric current passing through a filament. A cold cathode does not necessarily operate at a low temperature: it is often heated to its operating temperature by other methods, such as the current passing from the cathode into the gas.

A corona discharge is an electrical discharge caused by the ionization of a fluid such as air surrounding a conductor carrying a high voltage. It represents a local region where the air has undergone electrical breakdown and become conductive, allowing charge to continuously leak off the conductor into the air. A corona discharge occurs at locations where the strength of the electric field around a conductor exceeds the dielectric strength of the air. It is often seen as a bluish glow in the air adjacent to pointed metal conductors carrying high voltages, and emits light by the same mechanism as a gas discharge lamp. Corona discharges can also happen in weather, such as thunderstorms, where objects like ship masts or airplane wings have a charge significantly different from the air around them.

An electron gun is an electrical component in some vacuum tubes that produces a narrow, collimated electron beam that has a precise kinetic energy.

Paschen's law is an equation that gives the breakdown voltage, that is, the voltage necessary to start a discharge or electric arc, between two electrodes in a gas as a function of pressure and gap length. It is named after Friedrich Paschen who discovered it empirically in 1889.

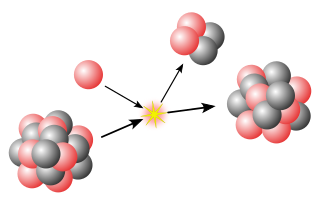

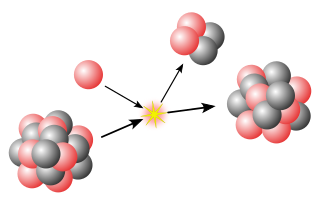

Neutron generators are neutron source devices which contain compact linear particle accelerators and that produce neutrons by fusing isotopes of hydrogen together. The fusion reactions take place in these devices by accelerating either deuterium, tritium, or a mixture of these two isotopes into a metal hydride target which also contains deuterium, tritium or a mixture of these isotopes. Fusion of deuterium atoms results in the formation of a helium-3 ion and a neutron with a kinetic energy of approximately 2.5 MeV. Fusion of a deuterium and a tritium atom results in the formation of a helium-4 ion and a neutron with a kinetic energy of approximately 14.1 MeV. Neutron generators have applications in medicine, security, and materials analysis.

A glow discharge is a plasma formed by the passage of electric current through a gas. It is often created by applying a voltage between two electrodes in a glass tube containing a low-pressure gas. When the voltage exceeds a value called the striking voltage, the gas ionization becomes self-sustaining, and the tube glows with a colored light. The color depends on the gas used.

A vacuum arc can arise when the surfaces of metal electrodes in contact with a good vacuum begin to emit electrons either through heating or in an electric field that is sufficient to cause field electron emission. Once initiated, a vacuum arc can persist, since the freed particles gain kinetic energy from the electric field, heating the metal surfaces through high-speed particle collisions. This process can create an incandescent cathode spot, which frees more particles, thereby sustaining the arc. At sufficiently high currents an incandescent anode spot may also be formed.

The gridded ion thruster is a common design for ion thrusters, a highly efficient low-thrust spacecraft propulsion method running on electrical power by using high-voltage grid electrodes to accelerate ions with electrostatic forces.

A Crookes tube is an early experimental electrical discharge tube, with partial vacuum, invented by English physicist William Crookes and others around 1869-1875, in which cathode rays, streams of electrons, were discovered.

Johann Wilhelm Hittorf was a German physicist who was born in Bonn and died in Münster, Germany.

The history of mass spectrometry has its roots in physical and chemical studies regarding the nature of matter. The study of gas discharges in the mid 19th century led to the discovery of anode and cathode rays, which turned out to be positive ions and electrons. Improved capabilities in the separation of these positive ions enabled the discovery of stable isotopes of the elements. The first such discovery was with the element neon, which was shown by mass spectrometry to have at least two stable isotopes: 20Ne and 22Ne. Mass spectrometers were used in the Manhattan Project for the separation of isotopes of uranium necessary to create the atomic bomb.

In electromagnetism, the Townsend discharge or Townsend avalanche is a ionisation process for gases where free electrons are accelerated by an electric field, collide with gas molecules, and consequently free additional electrons. Those electrons are in turn accelerated and free additional electrons. The result is an avalanche multiplication that permits electrical conduction through the gas. The discharge requires a source of free electrons and a significant electric field; without both, the phenomenon does not occur.

Eugen Goldstein was a German physicist. He was an early investigator of discharge tubes, the discoverer of anode rays or canal rays, later identified as positive ions in the gas phase including the hydrogen ion. He was the great uncle of the violinists Mikhail Goldstein and Boris Goldstein.