The ten years 1917–1927 saw a radical transformation of the Russian Empire into a socialist state, the Soviet Union. Soviet Russia covers 1917–1922 and Soviet Union covers the years 1922 to 1991. After the Russian Civil War (1917–1923), the Bolsheviks took control. They were dedicated to a version of Marxism developed by Vladimir Lenin. It promised the workers would rise, destroy capitalism, and create a socialist society under the leadership of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. The awkward problem, regarding Marxist revolutionary theory, was the small proletariat, in an overwhelmingly peasant society with limited industry and a very small middle class. Following the February Revolution in 1917 that deposed Nicholas II of Russia, a short-lived provisional government gave way to Bolsheviks in the October Revolution. The Bolshevik Party was renamed the Russian Communist Party (RCP).

Agitprop refers to an intentional, vigorous promulgation of ideas. The term originated in the Soviet Union where it referred to popular media, such as literature, plays, pamphlets, films, and other art forms, with an explicitly political message in favor of communism.

Władysław Gomułka was a Polish Communist politician. He was the de facto leader of post-war Poland from 1947 until 1948, and again from 1956 to 1970.

The interwar Communist Party of Poland was a communist party active in Poland during the Second Polish Republic. It resulted from a December 1918 merger of the Social Democracy of the Kingdom of Poland and Lithuania (SDKPiL) and the Polish Socialist Party – Left into the Communist Workers' Party of Poland. The communists were a small force in Polish politics.

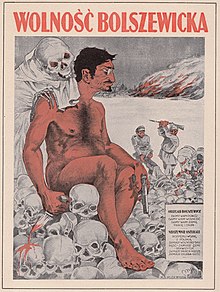

The Polish–Soviet War was fought primarily between the Second Polish Republic and the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic before it became a union republic in the aftermath of World War I and the Russian Revolution, on territories which were previously held by the Russian Empire and the Habsburg Monarchy following the Partitions of Poland.

The Polish minority in the Soviet Union are Polish diaspora who used to reside near or within the borders of the Soviet Union before its dissolution. Some of them continued to live in the post-Soviet states, most notably in Lithuania, Belarus, and Ukraine, the areas historically associated with the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, as well as in Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan among others.

The Polish Workers' Party was a communist party in Poland from 1942 to 1948. It was founded as a reconstitution of the Communist Party of Poland (KPP) and merged with the Polish Socialist Party (PPS) in 1948 to form the Polish United Workers' Party (PZPR). From the end of World War II the PPR led Poland, with the Soviet Union exercising moderate influence. During the PPR years, the centers of opposition activity were largely diminished, and a socialist system was established in the country.

Wanda Wasilewska, also known by her Russian name Vanda Lvovna Vasilevskaya, was a Polish and Soviet novelist and journalist and a left-wing political activist.

Wilhelm Adalbert Hosenfeld, originally a school teacher, was a German Army officer who by the end of the Second World War had risen to the rank of Hauptmann (captain). He helped to hide or rescue several Polish people, including Jews, in Nazi-German occupied Poland, and helped Jewish pianist and composer Władysław Szpilman to survive, hidden, in the ruins of Warsaw during the last months of 1944, an act which was portrayed in the 2002 film The Pianist. He was taken prisoner by the Red Army and died in Soviet captivity in 1952.

White or White-, was a political term used as an adjective, noun or a prefix by Bolsheviks to designate their real and alleged enemies of all sorts, by analogy with the White Army.

The 1920 Kiev offensive was a major part of the Polish–Soviet War. It was an attempt by the armed forces of the recently established Second Polish Republic led by Józef Piłsudski, in alliance with the Ukrainian People's Republic led by Symon Petliura, to seize the territories of modern-day Ukraine which mostly fell under Soviet control after the October Revolution as the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic.

Żydokomuna is an anti-communist and antisemitic canard, or a pejorative stereotype, suggesting that most Jews collaborated with the Soviet Union in importing communism into Poland, or that there was an exclusively Jewish conspiracy to do so. A Polish language term for "Jewish Bolshevism", or more literally "Jewish communism", Żydokomuna is related to the "Jewish world conspiracy" myth.

Western Belorussia or Western Belarus is a historical region of modern-day Belarus which belonged to the Second Polish Republic during the interwar period. For twenty years before the 1939 invasion of Poland, it was the northern part of the Polish Kresy macroregion. Following the end of World War II in Europe, most of Western Belorussia was ceded to the Soviet Union by the Allies, while some of it, including Białystok, was given to the Polish People's Republic. Until the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, Western Belorussia formed the western part of the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic (BSSR). Today, it constitutes the west of modern Belarus.

Propaganda in the Soviet Union was the practice of state-directed communication aimed at promoting class conflict, proletarian internationalism, the goals of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, and the party itself.

Jewish Bolshevism, also Judeo–Bolshevism, is an antisemitic conspiracy theory that claims that the Russian Revolution of 1917 was a Jewish plot and that Jews controlled the Soviet Union and international communist movements, often in furtherance of a plan to destroy Western civilization. It was one of the main Nazi beliefs that served as an ideological justification for the German invasion of the Soviet Union and the Holocaust.

Socialist realism in Poland was a socio-political and aesthetic doctrine enforced by the pro-Soviet communist government in the process of Stalinization of the post-war Polish People’s Republic. The official policy was introduced in 1949 by a decree of the Polish United Workers' Party minister Włodzimierz Sokorski. As in all Soviet-dominated Eastern Bloc countries, Socialist realism became the main instrument of political control in the building of totalitarianism in Poland. However, the trend never became truly dominant. Following Stalin's death, and especially from 1953 on, critical opinions were heard with increasing frequency. Finally, as part of the Gomułka political thaw from within the Polish United Workers' Party, the entire doctrine was officially given up in 1956. Following Bierut's death on March 12, 1956, and the subsequent De-Stalinization of all People's Republics, Polish artists, writers and architects started abandoning it around 1956.

The Communist Party of Lithuania and Byelorussia also known as the Communist Party (Bolsheviks) of Lithuania and Byelorussia, was a communist party which governed the short-lived Socialist Soviet Republic of Lithuania and Byelorussia in 1919. The Central Committee of the party had the status of a regional committee within the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks). Following the loss of Lithuania and Byelorussia to Polish forces in the Polish-Soviet war, the party organized partisan units behind the front lines. In September 1920 the party was disbanded into the Communist Party of Lithuania and the Communist Party (Bolsheviks) of Byelorussia.

Feliks Yakovlevich Kon was a Polish communist activist, politician, ethnographer, publicist and journalist. He was the editor-in-chief of the Soviet satirical magazine, Krokodil.

The Ukrainian War of Independence, also referred to as the Ukrainian–Soviet War in Ukraine, lasted from March 1917 to November 1921. It saw the establishment and development of an independent Ukrainian republic, most of which was absorbed into the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic between 1919 and 1920. The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic was one of the constituent republics of the Soviet Union between 1922 and 1991.

Operation Antyk, also known as Department R, was a complex of counter-propaganda activities of Polish resistance movement organisation Home Army, directed against pro-Soviet and pro-communist circles in Polish society, mostly members of the Polish Workers' Party. The operation was initiated by Office Antyk of the Home Army’s Bureau of Information and Propaganda. Begun in November 1943, it was directed by Tadeusz Żenczykowski.