Piero Sraffa, FBA was an influential Italian economist who served as lecturer of economics at the University of Cambridge. His book Production of Commodities by Means of Commodities is taken as founding the neo-Ricardian school of economics.

Business cycles are intervals of general expansion followed by recession in economic performance. The changes in economic activity that characterize business cycles have important implications for the welfare of the general population, government institutions, and private sector firms. There are numerous specific definitions of what constitutes a business cycle. The simplest and most naïve characterization comes from regarding recessions as 2 consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth. More satisfactory classifications are provided by, first including more economic indicators and second by looking for more informative data patterns than the ad hoc 2 quarter definition.

Classical economics, classical political economy, or Smithian economics is a school of thought in political economy that flourished, primarily in Britain, in the late 18th and early-to-mid-19th century. Its main thinkers are held to be Adam Smith, Jean-Baptiste Say, David Ricardo, Thomas Robert Malthus, and John Stuart Mill. These economists produced a theory of market economies as largely self-regulating systems, governed by natural laws of production and exchange.

Steve Keen is an Australian economist and author. He considers himself a post-Keynesian, criticising neoclassical economics as inconsistent, unscientific, and empirically unsupported.

The organic composition of capital (OCC) is a concept created by Karl Marx in his theory of capitalism, which was simultaneously his critique of the political economy of his time. It is derived from his more basic concepts of 'value composition of capital' and 'technical composition of capital'. Marx defines the organic composition of capital as "the value-composition of capital, in so far as it is determined by its technical composition and mirrors the changes of the latter". The 'technical composition of capital' measures the relation between the elements of constant capital and variable capital. It is 'technical' because no valuation is here involved. In contrast, the 'value composition of capital' is the ratio between the value of the elements of constant capital involved in production and the value of the labor. Marx found that the special concept of 'organic composition of capital' was sometimes useful in analysis, since it assumes that the relative values of all the elements of capital are constant.

Maurice Herbert Dobb was an English economist at Cambridge University and a Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge. He is remembered as one of the pre-eminent Marxist economists of the 20th century. Dobb was highly influential outside of economics, having helped to establish the Communist Party Historians Group which developed social history and attracted future members of the Cambridge Five to Marxism in the 1930s.

The value product (VP) is an economic concept formulated by Karl Marx in his critique of political economy during the 1860s, and used in Marxian social accounting theory for capitalist economies. Its annual monetary value is approximately equal to the netted sum of six flows of income generated by production:

The law of the value of commodities, known simply as the law of value, is a central concept in Karl Marx's critique of political economy first expounded in his polemic The Poverty of Philosophy (1847) against Pierre-Joseph Proudhon with reference to David Ricardo's economics. Most generally, it refers to a regulative principle of the economic exchange of the products of human work, namely that the relative exchange-values of those products in trade, usually expressed by money-prices, are proportional to the average amounts of human labor-time which are currently socially necessary to produce them within the capitalist mode of production.

Prices of production is a concept in Karl Marx's critique of political economy, defined as "cost-price + average profit". A production price can be thought of as a type of supply price for products; it refers to the price levels at which newly produced goods and services would have to be sold by the producers, in order to reach a normal, average profit rate on the capital invested to produce the products.

The tendency of the rate of profit to fall (TRPF) is a theory in the crisis theory of political economy, according to which the rate of profit—the ratio of the profit to the amount of invested capital—decreases over time. This hypothesis gained additional prominence from its discussion by Karl Marx in Chapter 13 of Capital, Volume III, but economists as diverse as Adam Smith, John Stuart Mill, David Ricardo and William Stanley Jevons referred explicitly to the TRPF as an empirical phenomenon that demanded further theoretical explanation, although they differed on the reasons why the TRPF should necessarily occur.

In the history of economic thought, a school of economic thought is a group of economic thinkers who share or shared a common perspective on the way economies work. While economists do not always fit into particular schools, particularly in modern times, classifying economists into schools of thought is common. Economic thought may be roughly divided into three phases: premodern, early modern and modern. Systematic economic theory has been developed mainly since the beginning of what is termed the modern era.

The temporal single-system interpretation (TSSI) of Karl Marx's value theory emerged in the early 1980s in response to renewed allegations that his theory was "riven with internal inconsistencies" and that it must therefore be rejected or corrected. The inconsistency allegations had been a prominent feature of Marxian economics and the debate surrounding it since the 1970s. Andrew Kliman argues that charges of inconsistency serve to legitimate the suppression of Marx's critique of political economy and current-day research based upon it as well as the "correction" of Marx's inconsistencies.

Nobuo Okishio was a Japanese Marxian economist and emeritus professor of Kobe University. In 1979, he was elected President of the Japan Association of Economics and Econometrics, which is now called Japanese Economic Association.

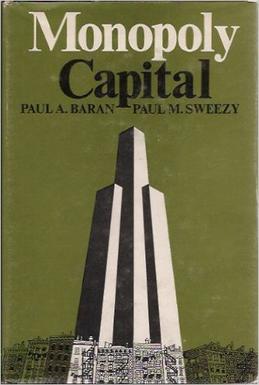

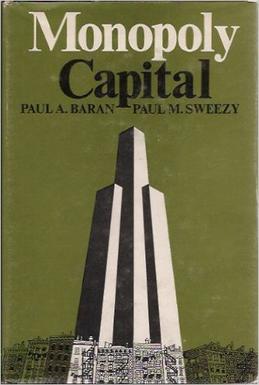

Monopoly Capital: An Essay on the American Economic and Social Order is a 1966 book by the Marxian economists Paul Sweezy and Paul A. Baran. It was published by Monthly Review Press. It made a major contribution to Marxian theory by shifting attention from the assumption of a competitive economy to the monopolistic economy associated with the giant corporations that dominate the modern accumulation process. Their work played a leading role in the intellectual development of the New Left in the 1960s and 1970s. As a review in the American Economic Review stated, it represented "the first serious attempt to extend Marx’s model of competitive capitalism to the new conditions of monopoly capitalism." It attracted renewed attention following the Great Recession.

Throughout modern history, a variety of perspectives on capitalism have evolved based on different schools of thought.

The Cambridge capital controversy, sometimes called "the capital controversy" or "the two Cambridges debate", was a dispute between proponents of two differing theoretical and mathematical positions in economics that started in the 1950s and lasted well into the 1960s. The debate concerned the nature and role of capital goods and a critique of the neoclassical vision of aggregate production and distribution. The name arises from the location of the principals involved in the controversy: the debate was largely between economists such as Joan Robinson and Piero Sraffa at the University of Cambridge in England and economists such as Paul Samuelson and Robert Solow at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States.

In Marxian economics, surplus value is the difference between the amount raised through a sale of a product and the amount it cost to manufacture it: i.e. the amount raised through sale of the product minus the cost of the materials, plant and labour power. The concept originated in Ricardian socialism, with the term "surplus value" itself being coined by William Thompson in 1824; however, it was not consistently distinguished from the related concepts of surplus labor and surplus product. The concept was subsequently developed and popularized by Karl Marx. Marx's formulation is the standard sense and the primary basis for further developments, though how much of Marx's concept is original and distinct from the Ricardian concept is disputed. Marx's term is the German word "Mehrwert", which simply means value added, and is cognate to English "more worth".

Marxian economics, or the Marxian school of economics, is a heterodox school of political economic thought. Its foundations can be traced back to Karl Marx's critique of political economy. However, unlike critics of political economy, Marxian economists tend to accept the concept of the economy prima facie. Marxian economics comprises several different theories and includes multiple schools of thought, which are sometimes opposed to each other; in many cases Marxian analysis is used to complement, or to supplement, other economic approaches. Because one does not necessarily have to be politically Marxist to be economically Marxian, the two adjectives coexist in usage, rather than being synonymous: They share a semantic field, while also allowing both connotative and denotative differences.

Crisis theory, concerning the causes and consequences of the tendency for the rate of profit to fall in a capitalist system, is associated with Marxian critique of political economy, and was further popularised through Marxist economics.

Marxism and Keynesianism is a method of understanding and comparing the works of influential economists John Maynard Keynes and Karl Marx. Both men's works has fostered respective schools of economic thought that have had significant influence in various academic circles as well as in influencing government policy of various states. Keynes' work found popularity in developed liberal economies following the Great Depression and World War II, most notably Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal in the United States in which strong industrial production was backed by strong unions and government support. Marx's work, with varying degrees of faithfulness, led the way to a number of socialist states, notably the Soviet Union and the People's Republic of China. The immense influence of both Marxian and Keynesian schools has led to numerous comparisons of the work of both economists along with synthesis of both schools.