Herāt is an oasis city and the third-largest city in Afghanistan. In 2020, it had an estimated population of 574,276, and serves as the capital of Herat Province, situated south of the Paropamisus Mountains in the fertile valley of the Hari River in the western part of the country. An ancient civilization on the Silk Road between West, Central and South Asia, it serves as a regional hub in the country's west.

Islamic architecture comprises the architectural styles of buildings associated with Islam. It encompasses both secular and religious styles from the early history of Islam to the present day. The Islamic world encompasses a wide geographic area historically ranging from western Africa and Europe to eastern Asia. Certain commonalities are shared by Islamic architectural styles across all these regions, but over time different regions developed their own styles according to local materials and techniques, local dynasties and patrons, different regional centers of artistic production, and sometimes different religious affiliations.

Balkh is a town in the Balkh Province of Afghanistan, about 20 km (12 mi) northwest of the provincial capital, Mazar-e Sharif, and some 74 km (46 mi) south of the Amu Darya river and the Uzbekistan border. Its population was recently estimated to be 138,594.

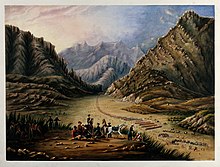

Afghanistan is a mountainous landlocked country at the crossroads of Central and South (Southern) Asia. Some of the invaders in the history of Afghanistan include the Maurya Empire, the ancient Macedonian Empire of Alexander the Great, the Rashidun Caliphate, the Mongol Empire led by Genghis Khan, the Timurid Empire of Timur, the Mughal Empire, various Persian Empires, the British Empire, the Soviet Union, and most recently the United States with a number of allies in response to the September 11 attacks. A reduced number of NATO troops remained in the country in support of the government under the U.S.–Afghanistan Strategic Partnership Agreement. Just prior to American withdrawal in 2021, the Taliban regained control of the capital Kabul and most of the country. They changed Afghanistan's official name to the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan.

The Timurid Empire was a late medieval, culturally Persianate Turco-Mongol empire that dominated Greater Iran in the early 15th century, comprising modern-day Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan, much of Central Asia, the South Caucasus, as well as parts of contemporary Pakistan, North India and Turkey. The empire was culturally hybrid, combining Turko-Mongolian and Persianate influences, with the last members of the dynasty being "regarded as ideal Perso-Islamic rulers".

Iranian architecture or Persian architecture is the architecture of Iran and parts of the rest of West Asia, the Caucasus and Central Asia. Its history dates back to at least 5,000 BC with characteristic examples distributed over a vast area from Turkey and Iraq to Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, and from the Caucasus to Zanzibar. Persian buildings vary greatly in scale and function, from vernacular architecture to monumental complexes. In addition to historic gates, palaces, and mosques, the rapid growth of cities such as the capital Tehran has brought about a wave of demolition and new construction.

Buddhism, an religion founded by Gautama Buddha, first arrived in modern-day Afghanistan through the conquests of Ashoka, the third emperor of the Maurya Empire. Among the earliest notable sites of Buddhist influence in the country is a bilingual mountainside inscription in Greek and Aramaic that dates back to 260 BCE and was found on the rocky outcrop of Chil Zena near Kandahar.

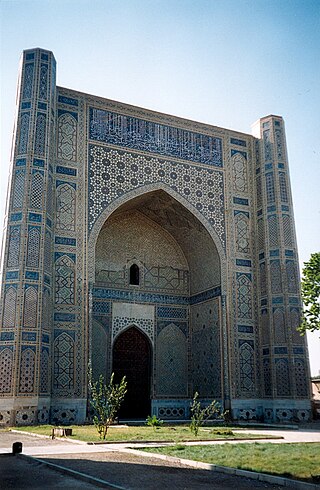

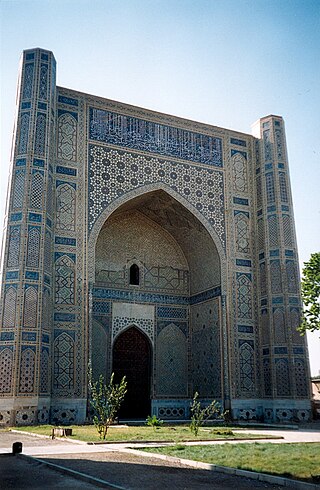

The Bibi-Khanym Mosque is one of the most important monuments of Samarkand, Uzbekistan. In the 15th century, it was one of the largest and most magnificent mosques in the Islamic world. It is considered a masterpiece of the Timurid Renaissance. By the mid-20th century, only a grandiose ruin of it still survived, but major parts of the mosque were restored during the Soviet period.

Po-i-Kalan, or Poi Kalan, is an Islamic religious complex located in Bukhara, Uzbekistan. The complex consists of three parts, the Kalan Mosque, the Kalan Minaret to which the name refers, and the Mir-i-Arab Madrasah. The positioning of the three structures creates a square courtyard in its center, with the Mir-i-Arab and the Kalan Mosque standing on opposite ends. In addition, the square is enclosed by a bazaar and a set of baths connected to the Minaret on the northern and southern ends respectively.

Architecture of Central Asia refers to the architectural styles of the numerous societies that have occupied Central Asia throughout history. These styles include a regional tradition of Islamic and Iranian architecture, including Timurid architecture of the 14th and 15th centuries, as well as 20th-century Soviet Modernism. Central Asia is an area that encompasses land from the Xinjiang Province of China in the East to the Caspian Sea in the West. The region is made up of the countries of Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Turkmenistan. The influence of Timurid architecture can be recognised in numerous sites in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, whilst the influence of Persian architecture is seen frequently in Uzbekistan and in some examples in Turkmenistan. Examples of Soviet architecture can be found in Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan.

The Jāmeh Mosque of Isfahān or Jāme' Mosque of Isfahān, also known as the Atiq Mosque and the Friday Mosque of Isfahān, is a historic congregational mosque (Jāmeh) of Isfahan, Iran. The mosque is the result of continual construction, reconstruction, additions and renovations on the site from around 771 to the end of the 20th century. The Grand Bazaar of Isfahan can be found towards the southwest wing of the mosque. It has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 2012. It is one of the largest and most important monuments of Islamic architecture in Iran.

Communities of various religious and ethnic background have lived in the land of what is now Afghanistan. Before the Islamic conquest, south of the Hindu Kush was ruled by the Zunbil and Kabul Shahi rulers. When the Chinese travellers visited Afghanistan between 399 and 751 AD, they mentioned that Hinduism and Buddhism was practiced in different areas between the Amu Darya in the north and the Indus River in the south. The land was ruled by the Kushans followed by the Hephthalites during these visits. It is reported that the Hephthalites were fervent followers of the Hindu god Surya.

The Great Mosque of Herat or "Jami Masjid of Herat", is a mosque in the city of Herat, in the Herat Province of north-western Afghanistan. It was built by the Ghurids, under the rule of Sultan Ghiyath al-Din Muhammad Ghori, who laid its foundation in 1200 CE. Later, it was extended several times as Herat changed rulers down the centuries from the Kartids, Timurids, Mughals and then the Uzbeks, all of whom supported the mosque. The fundamental structure of the mosque from the Ghurid period has been preserved, but parts have been added and modified. The Friday mosque in Herat was given its present appearance during the 20th century.

Muqarnas, also known in Iberian architecture as Mocárabe, is a form of ornamented vaulting in Islamic architecture. It is the archetypal form of Islamic architecture, integral to the vernacular of Islamic buildings. It was most likely first developed in eleventh-century Iraq, though the earliest preserved examples are also found outside this region.

Central Asian art is visual art created in Central Asia, in areas corresponding to modern Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Azerbaijan, Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and parts of modern Mongolia, China and Russia. The art of ancient and medieval Central Asia reflects the rich history of this vast area, home to a huge variety of peoples, religions and ways of life. The artistic remains of the region show a remarkable combinations of influences that exemplify the multicultural nature of Central Asian society. The Silk Road transmission of art, Scythian art, Greco-Buddhist art, Serindian art and more recently Persianate culture, are all part of this complicated history.

The Musalla complex, also known as the Musallah Complex or the Musalla of Gawhar Shah, is a former Islamic religious complex located in Herat, Afghanistan, containing examples of Timurid architecture. Much of the 15th-century complex is in ruins today, and the buildings that still stand are in need of restoration. The complex ruins consist of the five Musallah Minarets of Herat, the Mir Ali Sher Navai mausoleum, the Gawhar Shad Mausoleum, and the ruins of a large mosque and a madrasa complex.

Abbasid architecture developed in the Abbasid Caliphate between 750 and 1227, primarily in its heartland of Mesopotamia . The great changes of the Abbasid era can be characterized as at the same time political, geo-political and cultural. The Abbasid period starts with the destruction of the Umayyad ruling family and its replacement by the Abbasids, and the position of power is shifted to the Mesopotamian area. As a result there was a corresponding displacement of the influence of classical and Byzantine artistic and cultural standards in favor of local Mesopotamian models as well as Persian. The Abbasids evolved distinctive styles of their own, particularly in decoration. This occurred mainly during the period corresponding with their power and prosperity between 750 and 932.

Timurid architecture was an important stage in the architectural history of Iran and Central Asia during the late 14th and 15th centuries. The Timurid Empire (1370–1507), founded by Timur and conquering most of this region, oversaw a cultural renaissance. In architecture, the Timurid dynasty patronized the construction of palaces, mausoleums, and religious monuments across the region. Their architecture is distinguished by its grand scale, luxurious decoration in tilework, and sophisticated geometric vaulting. This architectural style, along with other aspects of Timurid art, spread across the empire and subsequently influenced the architecture of other empires from the Middle East to the Indian subcontinent.

The Timurid Renaissance was a historical period in Asian and Islamic history spanning the late 14th, the 15th, and the early 16th centuries. Following the gradual downturn of the Islamic Golden Age, the Timurid Empire, based in Central Asia ruled by the Timurid dynasty, witnessed the revival of arts and sciences. Its movement spread across the Muslim world. The French word renaissance means "rebirth", and defines a period as one of cultural revival. The use of the term for the description of this period has raised reservations among scholars, some of whom see it as a swan song of Timurid culture.

Timurid art is a style of art originating during the rule of the Timurid Empire (1370-1507) which had Turkic-Mongol roots and was spread across Iran and Central Asia. Timurid art was noted for its usage of both Persian and Chinese styles, as well as for taking influence from the art of other civilizations in Central Asia. Scholars regard this time period as an age of cultural and artistic excellence. After the decline of the Timurid Empire, the art of the civilization continued to influence other cultures in West and Central Asia.