The Lakota are a Native American people. Also known as the Teton Sioux, they are one of the three prominent subcultures of the Sioux people, with the Eastern Dakota (Santee) and Western Dakota (Wičhíyena). Their current lands are in North and South Dakota. They speak Lakȟótiyapi—the Lakota language, the westernmost of three closely related languages that belong to the Siouan language family.

The Sioux or Oceti Sakowin are groups of Native American tribes and First Nations people from the Great Plains of North America. The Sioux have two major linguistic divisions: the Dakota and Lakota peoples. Collectively, they are the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ, or "Seven Council Fires". The term "Sioux", an exonym from a French transcription ("Nadouessioux") of the Ojibwe term "Nadowessi", can refer to any ethnic group within the Great Sioux Nation or to any of the nation's many language dialects.

A sweat lodge is a low profile hut, typically dome-shaped or oblong, and made with natural materials. The structure is the lodge, and the ceremony performed within the structure may be called by some cultures a purification ceremony or simply a sweat.

Sitting Bull was a Hunkpapa Lakota leader who led his people during years of resistance against United States government policies. Sitting Bull was killed by Indian agency police on the Standing Rock Indian Reservation during an attempt to arrest him at a time when authorities feared that he would join the Ghost Dance movement.

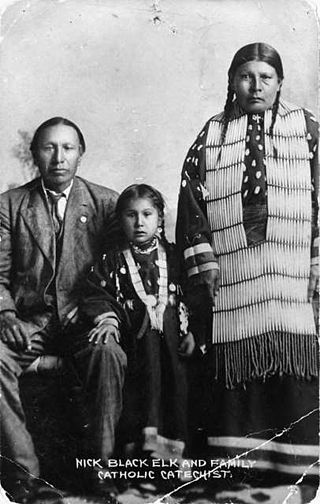

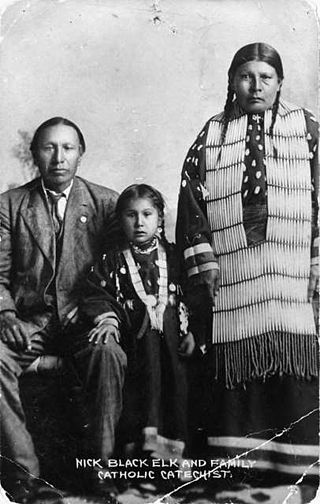

Heȟáka Sápa, commonly known as Black Elk, was a wičháša wakȟáŋ and heyoka of the Oglala Lakota people. He was a second cousin of the war leader Crazy Horse and fought with him in the Battle of Little Bighorn. He survived the Wounded Knee Massacre in 1890. He toured and performed in Europe as part of Buffalo Bill's Wild West.

White Buffalo Calf Woman or White Buffalo Maiden is a sacred woman of supernatural origin, central to the Lakota religion as the primary cultural prophet. Oral traditions relate that she brought the "Seven Sacred Rites" to the Lakota people.

A white buffalo or white bison is an American bison possessing white fur, and is considered sacred or spiritually significant in several Native American religions; therefore, such buffalo are often visited for prayer and other religious rituals. The coats of buffalo are almost always brown and their skin a dark brown or black; however, white buffalo can result from one of several physical conditions:

The Sun Dance is a ceremony practiced by some Native Americans in the United States and Indigenous peoples in Canada, primarily those of the Plains cultures. It usually involves the community gathering together to pray for healing. Individuals make personal sacrifices on behalf of the community.

Winter counts are pictorial calendars or histories in which tribal records and events were recorded by Native Americans in North America. The Blackfeet, Mandan, Kiowa, Lakota, and other Plains tribes used winter counts extensively. There are approximately one hundred winter counts in existence, many of which are duplicates.

The inípi ceremony, a type of sweat lodge, is a purification ceremony of the Lakota people. It is one of the Seven Sacred Ceremonies of the Lakota people, which has been passed down through the generations of Lakota.

Chanunpa is the Lakota language name for the sacred, ceremonial pipe and the ceremony in which it is used. The pipe ceremony is one of the Seven Sacred Rites of the Lakota people. Lakota tradition has it that White Buffalo Calf Woman brought the chanunpa to the people, as one of the Seven Sacred Rites, to serve as a sacred bridge between this world and Wakan Tanka, the "Great Mystery".

The Cheyenne River Indian Reservation was created by the United States in 1889 by breaking up the Great Sioux Reservation, following the attrition of the Lakota in a series of wars in the 1870s. The reservation covers almost all of Dewey and Ziebach counties in South Dakota. In addition, many small parcels of off-reservation trust land are located in Stanley, Haakon, and Meade counties.

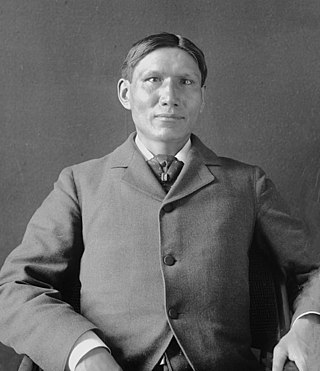

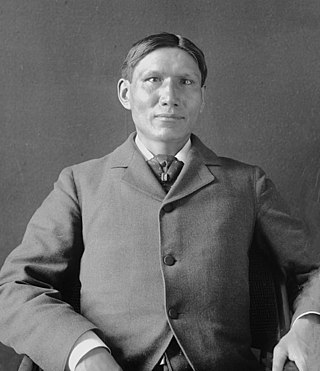

Iron Tail was an Oglala Lakota Chief and a star performer with Buffalo Bill's Wild West. Iron Tail was one of the most famous Native American celebrities of the late 19th and early 20th centuries and a popular subject for professional photographers who circulated his image across the continents. Iron Tail is notable in American history for his distinctive profile on the Buffalo nickel or Indian Head nickel of 1913 to 1938.

The Dakota are a Native American tribe and First Nations band government in North America. They compose two of the three main subcultures of the Sioux people, and are typically divided into the Eastern Dakota and the Western Dakota.

The Oglala are one of the seven subtribes of the Lakota people who, along with the Dakota, make up the Očhéthi Šakówiŋ. A majority of the Oglala live on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota, the eighth-largest Native American reservation in the United States.

Čhetáŋ Sápa(Black Hawk) (c. 1832 – c. 1890) was a medicine man and member of the Sans Arc or Itázipčho band of the Lakota people. He is most known for a series of 76 drawings that were later bound into a ledger book that depicts scenes of Lakota life and rituals. The ledger drawings were commissioned by William Edward Canton, a federal "Indian trader" at the Cheyenne River Indian Reservation. Black Hawk's drawings were drawn between 1880-1881. Today they are known as one of the most complete visual records of Lakota cosmology, ritual and daily life.

A ceremonial pipe is a particular type of smoking pipe, used by a number of cultures of the indigenous peoples of the Americas in their sacred ceremonies. Traditionally they are used to offer prayers in a religious ceremony, to make a ceremonial commitment, or to seal a covenant or treaty. The pipe ceremony may be a component of a larger ceremony, or held as a sacred ceremony in and of itself. Indigenous peoples of the Americas who use ceremonial pipes have names for them in each culture's Indigenous language. Not all cultures have pipe traditions, and there is no single word for all ceremonial pipes across the hundreds of diverse Native American languages.

The Wolf Award is an accolade conferred by a non-profit organization known as The Wolf Project to individuals, organizations, and communities in recognition of their efforts to reduce racial intolerance and to improve peace and understanding. The Wolf Award, which has also come to be known as The International Wolf Award, consists of a certificate of appreciation and a sculpture of a howling wolf, presented in ceremonial fashion to the recipient.

Zintkála Nuni, alternatively 'Zintka Lanuni', was a Lakota Sioux woman who was a 4-month-old infant when she was found alive among the victims at the Wounded Knee Massacre.

Lakota religion or Lakota spirituality is the traditional Native American religion of the Lakota people. It is practiced primarily in the North American Great Plains, within Lakota communities on reservations in North Dakota and South Dakota. The tradition has no formal leadership or organizational structure and displays much internal variation.