Flour is a powder made by grinding raw grains, roots, beans, nuts, or seeds. Flours are used to make many different foods. Cereal flour, particularly wheat flour, is the main ingredient of bread, which is a staple food for many cultures. Corn flour has been important in Mesoamerican cuisine since ancient times and remains a staple in the Americas. Rye flour is a constituent of bread in both Central Europe and Northern Europe.

Cornbread is a quick bread made with cornmeal, associated with the cuisine of the Southern United States, with origins in Native American cuisine. It is an example of batter bread. Dumplings and pancakes made with finely ground cornmeal are staple foods of the Hopi people in Arizona. The Hidatsa people of the Upper Midwest call baked cornbread naktsi, while the Choctaw people of the Southeast call it bvnaha. The Cherokee and Seneca tribes enrich the basic batter, adding chestnuts, sunflower seeds, apples, or berries, and sometimes combine it with beans or potatoes. Modern versions of cornbread are usually leavened by baking powder.

Soda bread is a variety of quick bread made in many cuisines in which sodium bicarbonate is used as a leavening agent instead of yeast. The basic ingredients of soda bread are flour, baking soda, salt, and buttermilk. The buttermilk contains lactic acid, which reacts with the baking soda to form bubbles of carbon dioxide. Other ingredients can be added, such as butter, egg, raisins, or nuts. Quick breads can be prepared quickly and reliably, without requiring the time and labor needed for kneaded yeast breads.

The dirham, dirhem or drahm is a unit of currency and of mass. It is the name of the currencies of Morocco, the United Arab Emirates and Armenia, and is the name of a currency subdivision in Jordan, Libya, Qatar and Tajikistan. It was historically a silver coin.

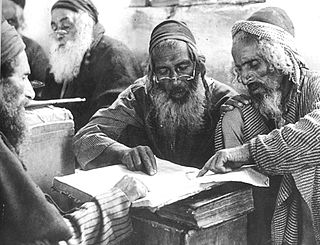

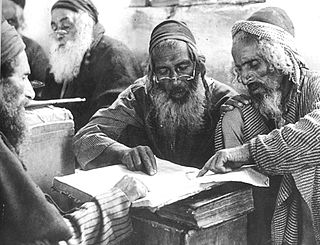

Yemenite Hebrew, also referred to as Temani Hebrew, is the pronunciation system for Hebrew traditionally used by Yemenite Jews. Yemenite Hebrew has been studied by language scholars, many of whom believe it retains older phonetic and grammatical features lost elsewhere. Yemenite speakers of Hebrew have garnered considerable praise from language purists because of their use of grammatical features from classical Hebrew.

Damper is a thick home-made bread traditionally prepared by early European settlers in Australia. It is a bread made from wheat-based dough. Flour, salt and water, with some butter if available, is kneaded and baked in the coals of a campfire, either directly or within a camp oven.

A flatbread is bread made usually with flour; water, milk, yogurt, or other liquid; and salt, and then thoroughly rolled into flattened dough. Many flatbreads are unleavened, although some are leavened, such as pita bread.

Showbread, in the King James Version shewbread, in a Biblical or Jewish context, refers to the cakes or loaves of bread which were always present, on a specially-dedicated table, in the Temple in Jerusalem as an offering to God. An alternative, and more appropriate, translation would be presence bread, since the Bible requires that the bread be constantly in the presence of God.

Johnnycake, also known as journey cake, johnny bread, hoecake, shawnee cake or spider cornbread, is a cornmeal flatbread, a type of batter bread. An early American staple food, it is prepared on the Atlantic coast from Newfoundland to Jamaica. The food originates from the indigenous people of North America. It is still eaten in the Bahamas, Belize, Nicaragua, Bermuda, Canada, Colombia, Curaçao, Dominican Republic, Jamaica, Puerto Rico, Saint Croix, Sint Maarten, Antigua, and the United States.

Yemeni cuisine is distinct from the wider Middle Eastern cuisines with regional variation. Although some foreign influences are evident in some regions of the country, the Yemeni kitchen is based on similar foundations across the country.

Lahoh, is a spongy, flat pancake-like bread. It is a type of flat bread eaten regularly in Somalia, Djibouti, Kenya, Ethiopia, Yemen and Saudi Arabia. Yemenite Jewish immigrants popularized the dish in Israel. It is called Canjeero/Canjeelo in southern Somalia and also called Laxoox/Lahoh in Somaliland, Djibouti, Yemen and Saudi Arabia respectively.

A tabun oven, or simply tabun, is a portable clay oven, shaped like a truncated cone. While all were made with a top opening, which could be used as a small stove top, some were made with an opening at the bottom from which to stoke the fire. Built and used even before biblical times as the family, neighbourhood, or village oven, tabun ovens continue to be built and used in parts of the Middle East today.

In Judaism, the dough offering is an assertive command requiring the owner of bread dough to give a part of the kneaded dough to a kohen. The obligation to separate the dough offering from the dough begins the moment the dough is kneaded, but may also be separated after the loaves are baked. This commandment is one of the twenty-four kohanic gifts, and, by a biblical injunction, is only obligatory in the Land of Israel, but from a rabbinic injunction applies also to breadstuffs made outside the Land of Israel.

Kubaneh is a traditional Yemenite Jewish yeast bread that is popular in Israel. It is traditionally baked overnight to be served for Shabbat breakfast. The bread is often served alongside haminados, and resek agvaniyot.

Taguella (tagǝlla) is a flatbread, the staple dish of Tuareg people living in the Sahara. It is a disk-shaped bread made from wheat flour and cooked buried underneath the hot sand and charcoal of a small fire. The bread is then broken up into small pieces and eaten with a meat sauce.

The primitive clay oven, or earthen oven / cob oven, has been used since ancient times by diverse cultures and societies, primarily for, but not exclusive to, baking before the invention of cast-iron stoves, and gas and electric ovens. The general build and shape of clay ovens were, mostly, common to all peoples, with only slight variations in size and in materials used to construct the oven. In primitive courtyards and farmhouses, earthen ovens were built on the ground.

Zalabiyeh is a fritter or doughnut found in several cuisines across the Arab world, West Asia and some parts of Europe influenced by the former. The fritter version is made from a semi-thin batter of wheat flour which is poured into hot oil and deep-fried. The earliest known recipe for the dish comes from a 10th-century Arabic cookbook and was originally made by pouring the batter through a coconut shell.

A fig-cake is a mass or lump of dried and compressed figs, usually formed by a mold into a round or square block for storage, or for selling in the marketplace for human consumption. The fig-cake is not a literal cake made as a pastry with a dough batter, but rather a thick and often hardened paste of dried and pressed figs made into a loaf, sold by weight and eaten as a snack or dessert food in Mediterranean countries and throughout the Near East. It is named "cake" only for its compacted shape when several are pounded and pressed together in a mold.

Dumb bread is a traditional bread that originates from the Virgin Islands. The name "dumb bread" comes from the cooking technique called dum pukht, originating from India and brought to the Caribbean when the Indian indentured workers replaced the slaves.