The North American B-25 Mitchell is an American medium bomber that was introduced in 1941 and named in honor of Brigadier General William "Billy" Mitchell, a pioneer of U.S. military aviation. Used by many Allied air forces, the B-25 served in every theater of World War II, and after the war ended, many remained in service, operating across four decades. Produced in numerous variants, nearly 10,000 B-25s were built, It was the most-produced American medium bomber and the third most-produced American bomber overall. These included several limited models such as the F-10 reconnaissance aircraft, the AT-24 crew trainers, and the United States Marine Corps' PBJ-1 patrol bomber.

Navigation is a field of study that focuses on the process of monitoring and controlling the movement of a craft or vehicle from one place to another. The field of navigation includes four general categories: land navigation, marine navigation, aeronautic navigation, and space navigation.

The Vickers Wellington was a British twin-engined, long-range medium bomber. It was designed during the mid-1930s at Brooklands in Weybridge, Surrey. Led by Vickers-Armstrongs' chief designer Rex Pierson; a key feature of the aircraft is its geodetic airframe fuselage structure, which was principally designed by Barnes Wallis. Development had been started in response to Air Ministry Specification B.9/32, issued in the middle of 1932, for a bomber for the Royal Air Force.

Celestial navigation, also known as astronavigation, is the practice of position fixing using stars and other celestial bodies that enables a navigator to accurately determine their actual current physical position in space or on the surface of the Earth without relying solely on estimated positional calculations, commonly known as dead reckoning. Celestial navigation is performed without using satellite navigation or other similar modern electronic or digital positioning means.

The Short Stirling was a British four-engined heavy bomber of the Second World War. It has the distinction of being the first four-engined bomber to be introduced into service with the Royal Air Force (RAF).

The Avro Lancaster is a British Second World War heavy bomber. It was designed and manufactured by Avro as a contemporary of the Handley Page Halifax, both bombers having been developed to the same specification, as well as the Short Stirling, all three aircraft being four-engined heavy bombers adopted by the Royal Air Force (RAF) during the same era.

The Battle of the Beams was a period early in the Second World War when bombers of the German Air Force (Luftwaffe) used a number of increasingly accurate systems of radio navigation for night bombing in the United Kingdom. British scientific intelligence at the Air Ministry fought back with a variety of their own increasingly effective means, involving jamming and deception signals. The period ended when the Wehrmacht moved their forces to the East in May 1941, in preparation for the attack on the Soviet Union.

A periscope is an instrument for observation over, around or through an object, obstacle or condition that prevents direct line-of-sight observation from an observer's current position.

The basic principles of air navigation are identical to general navigation, which includes the process of planning, recording, and controlling the movement of a craft from one place to another.

The Avro 679 Manchester was a British twin-engine heavy bomber developed and manufactured by the Avro aircraft company in the United Kingdom. While not being built in great numbers, it was the forerunner of the famed and vastly more successful four-engined Avro Lancaster, which was one of the most capable strategic bombers of the Second World War.

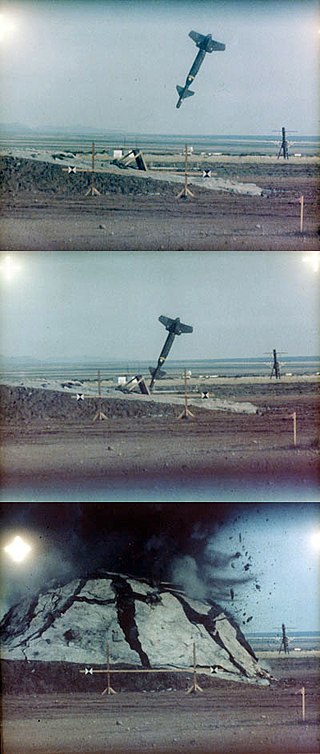

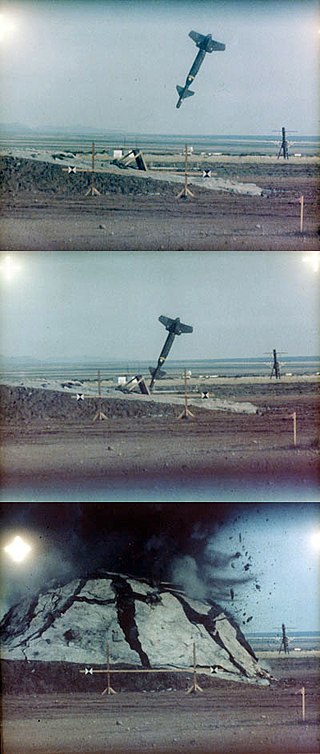

Missile guidance refers to a variety of methods of guiding a missile or a guided bomb to its intended target. The missile's target accuracy is a critical factor for its effectiveness. Guidance systems improve missile accuracy by improving its Probability of Guidance (Pg).

The Boeing T-43 is a retired modified Boeing 737-200 that was used by the United States Air Force for training navigators, now known as USAF combat systems officers, from 1973 to 2010. Informally referred to as the Gator and "Flying Classroom", nineteen of these aircraft were delivered to the Air Training Command (ATC) at Mather Air Force Base, California during 1973 and 1974. Two additional aircraft were delivered to the Colorado Air National Guard at Buckley Air National Guard Base and Peterson Air Force Base, Colorado, in direct support of cadet air navigation training at the nearby U.S. Air Force Academy. Two T-43s were later converted to CT-43As in the early 1990s and transferred to Air Mobility Command (AMC) and United States Air Forces in Europe (USAFE), respectively, as executive transports. A third aircraft was also transferred to Air Force Materiel Command (AFMC) for use as the "Rat 55" radar test bed aircraft and was redesignated as an NT-43A. The T-43A was retired by the Air Education and Training Command (AETC) in 2010 after 37 years of service.

The Avro Anson is a British twin-engine, multi-role aircraft built by the aircraft manufacturer Avro. Large numbers of the type served in a variety of roles for the Royal Air Force (RAF), Fleet Air Arm (FAA), Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF), Royal Australian Air Force and numerous other air forces before, during, and after the Second World War.

The Armstrong Whitworth A.W.38 Whitley was a British medium bomber aircraft of the 1930s. It was one of three twin-engined, front line medium bomber types that were in service with the Royal Air Force (RAF) at the outbreak of the Second World War. Alongside the Vickers Wellington and the Handley Page Hampden, the Whitley was developed during the mid-1930s according to Air Ministry Specification B.3/34, which it was subsequently selected to meet. In 1937, the Whitley formally entered into RAF squadron service; it was the first of the three medium bombers to be introduced.

The Airspeed AS.10 Oxford is a twin-engine monoplane aircraft developed and manufactured by Airspeed. It saw widespread use for training British Commonwealth aircrews in navigation, radio-operating, bombing and gunnery roles throughout the Second World War.

The Handley Page Halifax is a British Royal Air Force (RAF) four-engined heavy bomber of the Second World War. It was developed by Handley Page to the same specification as the contemporary twin-engine Avro Manchester.

Aircrew, also called flight crew, are personnel who operate an aircraft while in flight. The composition of a flight's crew depends on the type of aircraft, plus the flight's duration and purpose.

The Tupolev Tu-14, was a Soviet twinjet light bomber derived from the Tupolev '73', the failed competitor to the Ilyushin Il-28 'Beagle'. It was used as a torpedo bomber by the mine-torpedo regiments of Soviet Naval Aviation between 1952–1959 and exported to the People's Republic of China.

The aircrews of RAF Bomber Command during World War II operated a fleet of bomber aircraft carried strategic bombing operations from September 1939 to May 1945, on behalf of the Allied powers. The crews were men from the United Kingdom, other Commonwealth countries, and occupied Europe, especially Poland, France, Czechoslovakia and Norway, as well as other foreign volunteers. While the majority of Bomber Command personnel were members of the RAF, many belonged to other air forces – especially the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF), Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) and Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF). Under Article XV of the 1939 Air Training Agreement, squadrons belonging officially to the RCAF, RAAF, and RNZAF were formed, equipped and financed by the RAF, for service in Europe. While it was intended that RCAF, RAAF, and RNZAF personnel would serve only with their respective "Article XV squadrons", in practice many were posted to units of the RAF or other air forces. Likewise many RAF personnel served in Article XV squadrons.

The bubble octant and bubble sextant are air navigation instruments. Although an instrument may be called a "bubble sextant", it may actually be a bubble octant.