To Kill a Mockingbird is a novel by the American author Harper Lee. It was published in June 1960 and became instantly successful. In the United States, it is widely read in high schools and middle schools. To Kill a Mockingbird has become a classic of modern American literature; a year after its release, it won the Pulitzer Prize. The plot and characters are loosely based on Lee's observations of her family, her neighbors and an event that occurred near her hometown of Monroeville, Alabama, in 1936, when she was ten.

Monroeville is the county seat of Monroe County, Alabama, United States. At the 2020 census its population was 5,951.

Nelle Harper Lee was an American novelist whose 1960 novel To Kill a Mockingbird won the 1961 Pulitzer Prize and became a classic of modern American literature. She assisted her close friend Truman Capote in his research for the book In Cold Blood (1966). Her second and final novel, Go Set a Watchman, was an earlier draft of Mockingbird that was published in July 2015 as a sequel.

Matthew Avery Modine is an American actor. He rose to prominence through his role as U.S. Marine Private/Sergeant J.T. "Joker" Davis in Stanley Kubrick's Full Metal Jacket (1987). Other films include Birdy (1984), Vision Quest (1985), Married to the Mob (1988), Gross Anatomy (1989), Pacific Heights (1990), Short Cuts (1993), Cutthroat Island (1995), The Dark Knight Rises (2012), and Oppenheimer (2023). On television, he portrayed Dr. Don Francis in the HBO film And the Band Played On (1993), the oversexed Sullivan Groff on Weeds (2007), Ivan Turing in Proof (2015), and Dr. Martin Brenner in Netflix's Stranger Things (2016–2022).

The legal thriller genre is a type of crime fiction genre that focuses on the proceedings of the investigation, with particular reference to the impacts on courtroom proceedings and the lives of characters.

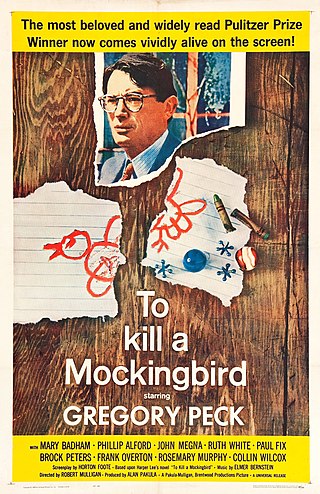

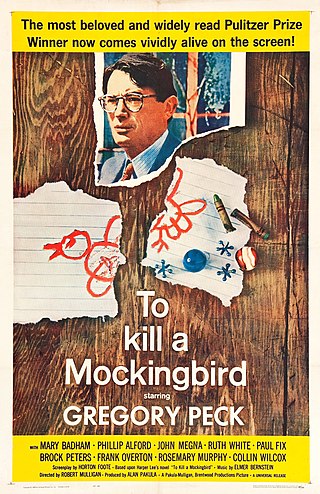

Mary Badham is an American actress who portrayed Jean Louise "Scout" Finch in To Kill a Mockingbird (1962), for which she was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress. At the time, Badham was the youngest actress ever nominated in this category.

To Kill a Mockingbird is a 1962 American coming-of-age legal drama crime film directed by Robert Mulligan. The screenplay by Horton Foote is based on Harper Lee's 1960 Pulitzer Prize–winning novel of the same name. The film stars Gregory Peck as Atticus Finch and Mary Badham as Scout. It marked the film debut of Robert Duvall, William Windom, and Alice Ghostley.

Since the publication ofTo Kill a Mockingbird in 1960, there have been many references and allusions to it in popular culture. The book has been internationally popular for more than a half century, selling more than 30 million copies in 40 languages. It currently (2013) sells 750,000 copies a year and is widely read in schools in America and abroad. Harper Lee and her publisher did not expect To Kill a Mockingbird to be such a huge success. Since it was first published in 1960, it has sold close to one million copies a year and has been the second-best-selling backlist title in the United States. Whether they like the book or not, readers can remember when and where they were the first time they opened the book. Because of this, Mockingbird has become a pillar for students around the country and symbol of justice and the reminiscence of childhood. To Kill a Mockingbird is not solely about the cultural legal practices of Atticus Finch, but about the fatherly virtues he held towards his children and the way Scout viewed him as a father.

Atticus is a brand of clothing founded in 2001 by Blink-182 members Mark Hoppus and Tom DeLonge, along with their childhood friend Dylan Anderson.

Amasa Coleman Lee was an American newspaper editor, politician, and lawyer. He was the father of acclaimed novelist Harper Lee.

The Old Monroe County Courthouse is a historic courthouse building in Monroeville, Alabama that served as the Monroe County courthouse from 1903 to 1963.

Finchburg is an unincorporated community in Monroe County, Alabama, United States. Amasa Coleman Lee, lawyer, legislator, and the father of Harper Lee, lived and worked in Finchburg.

Go Set a Watchman is a novel by Harper Lee that was published in 2015 by HarperCollins (US) and Heinemann (UK). Written before her only other published novel, the Pulitzer Prize-winning To Kill a Mockingbird (1960), Go Set a Watchman was initially promoted as a sequel by its publishers. It is now accepted that it was a first draft of To Kill a Mockingbird, with many passages in that book being used again.

Therese von Hohoff Torrey, better known as Tay Hohoff, was an American literary editor with the publishing firm J. B. Lippincott & Co. Strong-willed and forceful, she worked closely with author Harper Lee over the course of two years to give final shape to her classic novel To Kill A Mockingbird. After the commercial and literary success of the novel, she shielded Harper Lee from the intense pressure to write another one. She retired from a senior editorial position at the firm in 1973 and died the following year.

Alabama literature includes the prose fiction, poetry, films and biographies that are set in or created by those from the US state of Alabama. This literature officially began emerging from the state circa 1819 with the recognition of the region as a state. Like other forms of literature from the South, Alabama literature often discusses issues of race, stemming from the history of the slave society, the American Civil War, the Reconstruction era and Jim Crow laws, and the US Civil Rights Movement. Alabama literature was inspired by the latter's significant campaigns and events in the state, such as the Montgomery Bus Boycott and Selma to Montgomery marches.

To Kill a Mockingbird is a 2018 play based on the 1960 novel of the same name by Harper Lee, adapted for the stage by Aaron Sorkin. It opened on Broadway at the Shubert Theatre on December 13, 2018. The play opened in London's West End at the Gielgud Theatre in March 2022. The show follows the story of Atticus Finch, a lawyer in 1930s Alabama, as he defends Tom Robinson, a black man falsely accused of rape. Varying from the book, the play has Atticus as the protagonist, not his daughter Scout, allowing his character to change throughout the show. During development the show was involved in two legal disputes, the first with the Lee estate over the faithfulness of the play to the original book, and the second was due to exclusivity to the rights with productions using an earlier script by Christopher Sergel. During opening week, the production garnered more than $1.5 million in box office sales and reviews by publications such as the New York Times, LA Times and AMNY were positive but not without criticism.

The Monroe Journal is a weekly newspaper from Monroeville, Alabama serving the city and surrounding area.

Calpurnia is a 2018 play by Canadian playwright Audrey Dwyer. It is named after Calpurnia, a character in Harper Lee's To Kill A Mockingbird.

Atticus is a masculine name of Greek origin meaning “from Attica.” The name is often used in reference to Atticus Finch, a heroic lawyer who represents an African American man accused of rape by a white woman in a racist Southern United States town in Harper Lee’s 1960 novel To Kill a Mockingbird. Usage of the name continued to increase even after the publication of the 2015 sequel Go Set a Watchman, a novel which presents a more conflicted version of Atticus Finch who also holds racist beliefs. The name has been steadily increasing in usage in the United States. It has been among the top 1,000 names for boys in the United States since 2004 and among the top 300 since 2020.