The Via Francigena is an ancient road and pilgrimage route running from the cathedral city of Canterbury in England, through France and Switzerland, to Rome and then to Apulia, Italy, where there were ports of embarkation for the Holy Land. It was known in Italy as the "Via Francigena" or the "Via Romea Francigena". In medieval times it was an important road and pilgrimage route for those wishing to visit the Holy See and the tombs of the apostles Peter and Paul.

The Congridae are the family of conger and garden eels. Congers are valuable and often large food fishes, while garden eels live in colonies, all protruding from the sea floor after the manner of plants in a garden. The family includes over 180 species in 32 genera.

Kogiinae is a subfamily of sperm whales of the family Kogiidae comprising the genera Kogia and the extinct Praekogia.

The Magra is a 62-kilometre (39 mi) long river of Northern Italy, which runs through Pontremoli, Filattiera, Villafranca in Lunigiana and Aulla in the province of Massa-Carrara (Tuscany); Santo Stefano di Magra, Vezzano Ligure, Arcola, Sarzana and Ameglia in the province of La Spezia (Liguria).

Cene is a comune (municipality) in the Province of Bergamo in the Italian region of Lombardy, located about 60 kilometres (37 mi) northeast of Milan and about 15 kilometres (9 mi) northeast of Bergamo.

Nannolytoceras is an extinct genus of lytoceratid ammonite, family Lytoceratidae, with a stratigraphic range extending from the Bajocian age to Bathonian age.

Apateodus is a genus of prehistoric marine ray-finned fish which was described by Woodward in 1901. It was a relative of modern lizardfish and lancetfish in the order Aulopiformes, and one of a number of prominent nektonic aulopiforms of Cretaceous marine ecosystems.

Tectonatica is a genus of sea snails, marine gastropod molluscs in the subfamily Naticinae of the family Naticidae, the moon snails.

The European Land Mammal Mega Zones are zones in rock layers that have a specific assemblage of fossils (biozones) based on occurrences of fossil assemblages of European land mammals. These biozones cover most of the Cenozoic, with particular focus having been paid to the Neogene and Paleogene systems, the Quaternary has several competing systems. In cases when fossils of mammals are abundant, stratigraphers and paleontologists can use these biozones as a more practical regional alternative to the stages of the official ICS geologic timescale. European Land Mammal Mega Zones are often also confusingly referred to as ages, stages, or intervals.

Felis lunensis, or the Martelli's cat is an extinct felid of the subfamily Felinae.

The Calcare di Cellina (Italian for Cellina Limestone, is a Hauterivian to Aptian geologic formation in Friulia-Venezia Giulia, Italy. Fossil sauropod tracks have been reported from the formation.

Saurichthyiformes is an extinct order of ray-finned fish which existed in Asia, Africa, Australia, Europe and North America, during the late Permian to early Middle Jurassic. Saurichthyiiformes comprise two families, Saurichthyidae and Yelangichthyidae. Yelangichthyidae is monotypic, containing only the genus Yelangichthys. The gar or needlefish-like Saurichthyidae is primarily known from the genus Saurichthys. Additionally, the subgenera SaurorhynchusCostasaurichthys, Eosaurichthys, Lepidosaurichthys, and Sinosaurichthys are frequently used to group species, and are sometimes considered separate genera. Species are known from both marine end freshwater deposits. They had their highest diversity during the Early and Middle Triassic. Their phylogenetic position is uncertain, while they have often been considered members of Chondrostei, and thus related to living sturgeons and paddlefish, phylogenetic analysis of well-preserved remains has considered this relationship equivocal. They may actually belong to the stem-group of Actinopterygii, and thus not closely related to any living group of ray-finned fish.

The Laborcita Formation is a geologic formation in the Sacramento Mountains of New Mexico. It preserves fossils dating back to the late Pennsylvanian to early Permian.

The Corona Formation is a geologic formation of the Carnian Alps at the border of Austria and Italy. It preserves fossils dated to the Gzhelian stage of the Late Carboniferous period.

The Schlern Formation, also known as Schlern Dolomite, and Sciliar Formation or Sciliar Dolomite in Italy, is a limestone, marl and dolomite formation in the Southern Limestone Alps in Kärnten, Austria and South Tyrol, Italy.

Kogia pusilla is an extinct species of sperm whale from the Middle Pliocene of Italy related to the modern-day dwarf sperm whale and pygmy sperm whale. It is known from a single skull discovered in 1877, and was considered a species of beaked whale until 1997. The skull shares many characteristics with other sperm whales, and is comparable in size to that of the dwarf sperm whale. Like the modern Kogia, it probably hunted squid in the twilight zone, and frequented continental slopes. The environment it inhabited was likely a calm, nearshore area with a combination sandy and hard-rock seafloor. K. pusilla likely died out due to the ice ages at the end of the Pliocene.

The Marne di Monte Serrone is a geological formation in Italy, dating to roughly between 181 and 178 million years ago, and covering the early and middle Toarcian stage of the Jurassic Period of central Italy. It is the regional equivalent to the Toarcian units of Spain such as the Turmiel Formation, units in Montenegro, such as the Budoš Limestone and units like the Tafraout Formation of Morocco.

The bridge of Caprigliola was also known as the Albiano bridge, the Albiano Magra bridge or the Ponte di Albiano Magra.

Raibliania is an extinct genus of tanystropheid archosauromorph discovered in the Calcare del Predil Formation in Italy. It lived during the Carnian stage of the Late Triassic and it was related to Tanystropheus. Raibliania is distinct from Tanystropheus due to some distinct features of the cervical vertebrae and teeth. The type species is Raibliania calligarisi, named in 2020. The holotype consists of a partial post-cranial skeleton, with the known elements including vertebrae, a single tooth, several ribs, gastralia and parts of the pelvis.

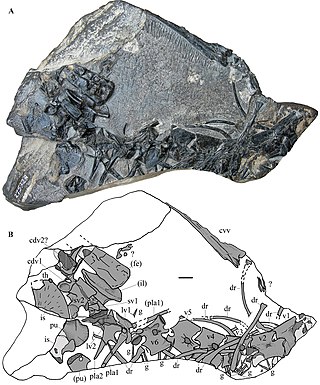

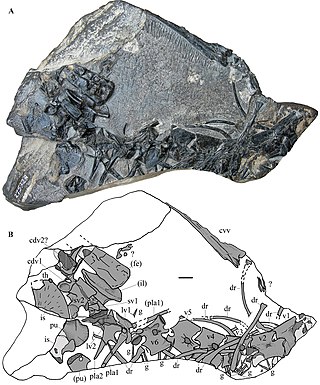

Neoproscinetes is a genus of extinct pycnodontid fish from the Cretaceous Santana Formation of Brazil. Fossils of this species have also been discovered in the Riachuelo Formation.