Theodore Herman Albert Dreiser was an American novelist and journalist of the naturalist school. His novels often featured main characters who succeeded at their objectives despite a lack of a firm moral code, and literary situations that more closely resemble studies of nature than tales of choice and agency. Dreiser's best known novels include Sister Carrie (1900) and An American Tragedy (1925).

Harry Sinclair Lewis was an American novelist, short-story writer, and playwright. In 1930, he became the first author from the United States to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature, which was awarded "for his vigorous and graphic art of description and his ability to create, with wit and humor, new types of characters." Lewis wrote six popular novels: Main Street (1920), Babbitt (1922), Arrowsmith (1925), Elmer Gantry (1927), Dodsworth (1929), and It Can't Happen Here (1935).

Henry Louis Mencken was an American journalist, essayist, satirist, cultural critic, and scholar of American English. He commented widely on the social scene, literature, music, prominent politicians, and contemporary movements. His satirical reporting on the Scopes Trial, which he dubbed the "Monkey Trial", also gained him attention. The term Menckenian has entered multiple dictionaries to describe anything of or pertaining to Mencken, including his combative rhetorical and prose style.

The bourgeoisie is a class of business owners and merchants which emerged in the Late Middle Ages, originally as a "middle class" between peasantry and aristocracy. They are traditionally contrasted with the proletariat by their wealth, political power, and education, as well as their access to and control of cultural, social and financial capital.

Dodsworth is a satirical novel by American writer Sinclair Lewis, first published by Harcourt Brace & Company on March 14, 1929. Its subject, the differences between US and European intellect, manners, and morals, is one that frequently appears in the works of Henry James.

Elmer Gantry is a satirical novel written by Sinclair Lewis in 1926 that presents aspects of the religious activity of the United States in fundamentalist and evangelistic circles and the attitudes of the 1920s public toward it. Reverend Dr. Elmer Gantry, the protagonist, is attracted by drinking, making easy money and chasing women. After various forays into smaller, fringe churches, he becomes a major moral and political force in the Methodist Church despite his hypocrisy and serial sexual indiscretions.

Boosterism is the act of promoting ("boosting") a town, city, or organization, with the goal of improving public perception of it. Boosting can be as simple as talking up the entity at a party or as elaborate as establishing a visitors' bureau.

Main Street is a satirical novel written by Sinclair Lewis, and published in 1920.

Winnemac is a fictional U.S. state invented by the writer Sinclair Lewis. His novel Babbitt takes place in Zenith, its largest city. Winnemac is also a setting for Gideon Planish, Arrowsmith, Elmer Gantry, and Dodsworth.

George Babbitt may refer to:

Edwin DuBose Heyward was an American author best known for his 1925 novel Porgy. He and his wife Dorothy, a playwright, adapted it as a 1927 play of the same name. The couple worked with composer George Gershwin to adapt the work as the 1935 opera Porgy and Bess. It was later adapted as a 1959 film of the same name.

Ilium is a fictional town in eastern New York state, used as a setting for many of Kurt Vonnegut's novels and stories, including Player Piano, Cat's Cradle, Slaughterhouse-Five, and the stories "Deer in the Works", "Poor Little Rich Town", and "Ed Luby's Key Club". The town is dominated by its major industry leader, the Ilium Works, which produces scientific marvels to assist, or possibly harm, human life. The Ilium Works is Vonnegut's symbol for the "impersonal corporate giant" with the power to alter humankind's destiny. The town has been compared to Zenith, the fictional setting in Sinclair Lewis's 1922 novel Babbitt.

Irving Babbitt was an American academic and literary critic, noted for his founding role in a movement that became known as the New Humanism, a significant influence on literary discussion and conservative thought in the period between 1910 and 1930. He was a cultural critic in the tradition of Matthew Arnold and a consistent opponent of romanticism, as represented by the writings of Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Politically he can, without serious distortion, be called a follower of Aristotle and Edmund Burke. He was an advocate of classical humanism but also offered an ecumenical defense of religion. His humanism implied a broad knowledge of various moral and religious traditions. His book Democracy and Leadership (1924) is regarded as a classic text of political conservatism. Babbitt is regarded as a major influence over American cultural and political conservatism.

The word hobbit was used by J. R. R. Tolkien as the name of a race of small humanoids in his fantasy fiction, the first published being The Hobbit in 1937. The Oxford English Dictionary, which added an entry for the word in the 1970s, credits Tolkien with coining it. Since then, however, it has been noted that there is prior evidence of the word, in a 19th-century list of legendary creatures. In 1971, Tolkien stated that he remembered making up the word himself, admitting that there was nothing but his "nude parole" to support the claim that he was uninfluenced by such similar words as hobgoblin. His choice may have been affected on his own admission by the title of Sinclair Lewis's 1922 novel Babbitt. The Tolkien scholar Tom Shippey has pointed out several parallels, including comparisons in The Hobbit, with the word "rabbit".

Joseph Hergesheimer was an American writer of the early 20th century known for his naturalistic novels of decadent life amongst the very wealthy.

The Smart Set was an American monthly literary magazine, founded by Colonel William d'Alton Mann and published from March 1900 to June 1930. Its headquarters was in New York City. During its Jazz Age heyday under the editorship of H. L. Mencken and George Jean Nathan, The Smart Set offered many up-and-coming authors their start and gave them access to a relatively large audience.

Mark Schorer was an American writer, critic, and scholar born in Sauk City, Wisconsin.

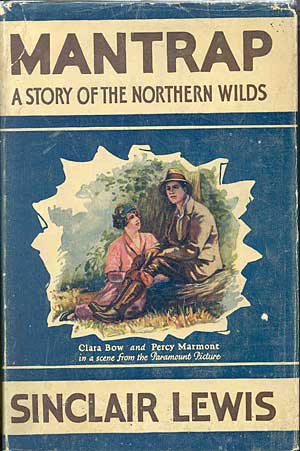

Mantrap is a 1926 novel by Sinclair Lewis. One of Lewis's two unsuccessful novels of the 1920s, the other being The Man Who Knew Coolidge. Mantrap is the story of New York lawyer Ralph Prescott's journey into the wilds of Saskatchewan, and of his adventures there. The novel spawned two separate film adaptations, Mantrap (1926), and Untamed (1940).

The Man Who Knew Coolidge is a 1928 satirical novel by Sinclair Lewis. It features the return of several characters from Lewis' previous works, including George Babbitt and Elmer Gantry. Additionally, it sees a return to the familiar territory of Lewis' fictional American city of Zenith, in the state of Winnemac. Presented as six long, uninterrupted monologues by Lowell Schmaltz, a travelling salesman in office supplies, the eponymous first section was originally published in The American Mercury in 1927.

The 1930 Nobel Prize in Literature was awarded to the American novelist Sinclair Lewis (1885–1951) "for his vigorous and graphic art of description and his ability to create, with wit and humour, new types of characters." He is the first American Nobel laureate in literature.