Tagalog is an Austronesian language spoken as a first language by the ethnic Tagalog people, who make up a quarter of the population of the Philippines, and as a second language by the majority. Its standardized form, officially named Filipino, is the national language of the Philippines, and is one of two official languages, alongside English.

Filipino is a language under the Austronesian language family. It is the national language of the Philippines, and one of the two official languages of the country, with English. It is a standardized variety of Tagalog based on the native dialect, spoken and written, in Metro Manila, the National Capital Region, and in other urban centers of the archipelago. The 1987 Constitution mandates that Filipino be further enriched and developed by the other languages of the Philippines.

Taglish or Englog is code-switching and/or code-mixing in the use of Tagalog and English, the most common languages of the Philippines. The words Taglish and Englog are portmanteaus of the words Tagalog and English. The earliest use of the word Taglish dates back to 1973, while the less common form Tanglish is recorded from 1999.

In the indigenous religion of the ancient Tagalogs, Bathalà/Maykapál was the transcendent Supreme God, the originator and ruler of the universe. He is commonly known and referred to in the modern era as Bathalà, a term or title which, in earlier times, also applied to lesser beings such as personal tutelary spirits, omen birds, comets, and other heavenly bodies which the early Tagalog people believed predicted events. It was after the arrival of the Spanish missionaries in the Philippines in the 16th century that Bathalà /Maykapál came to be identified with the Christian God, hence its synonymy with Diyós. Over the course of the 19th century, the term Bathala was totally replaced by Panginoón (Lord) and Diyós (God). It was no longer used until it was popularized again by Filipinos who learned from chronicles that the Tagalogs' indigenous God was called Bathalà.

Chavacano or Chabacano is a group of Spanish-based creole language varieties spoken in the Philippines. The variety spoken in Zamboanga City, located in the southern Philippine island group of Mindanao, has the highest concentration of speakers. Other currently existing varieties are found in Cavite City and Ternate, located in the Cavite province on the island of Luzon. Chavacano is the only Spanish-based creole in Asia. The 2020 Census of Population and Housing counted 106,000 households generally speaking Chavacano.

Kapampangan, Capampáñgan, or Pampangan is an Austronesian language, and one of the eight major languages of the Philippines. It is the primary and predominant language of the entire province of Pampanga and southern Tarlac, on the southern part of Luzon's central plains geographic region, where the Kapampangan ethnic group resides. Kapampangan is also spoken in northeastern Bataan, as well as in the provinces of Bulacan, Nueva Ecija, and Zambales that border Pampanga. It is further spoken as a second language by a few Aeta groups in the southern part of Central Luzon. The language is known honorifically as Amánung Sísuan.

Maranao is an Austronesian language spoken by the Maranao people in the provinces of Lanao del Sur and Lanao del Norte and the cities of Marawi and Iligan City in the Philippines, as well as in Sabah, Malaysia. It is a subgroup of the Danao languages of the Moros in the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao.

Filipino psychology, or Sikolohiyang Pilipino, in Filipino, is defined as the philosophical school and psychology rooted on the experience, ideas, and cultural orientation of the Filipinos. It was formalized in 1975 by the Pambansang Samahan sa Sikolohiyang Pilipino under the leadership of Virgilio Enriquez, who is regarded by many as the father of Filipino Psychology. Sikolohiyang Pilipino movement is a movement that created to address the colonial background in psychology in the country. It focuses on various themes such as identity and national consciousness, social awareness, and involvement, and it uses indigenous psychology to apply to various fields such as religion, mass media, and health.

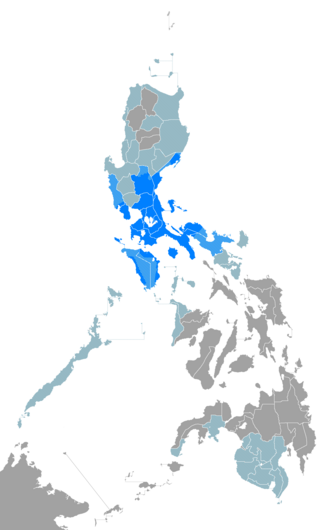

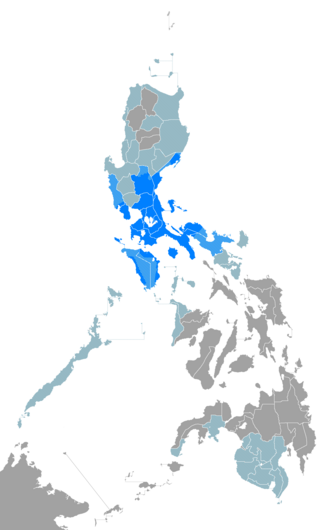

The Tagalog people are native to the Philippines, particularly the Metro Manila and Calabarzon regions and Marinduque province of southern Luzon, and comprise the majority in the provinces of Bulacan, Bataan, Nueva Ecija, Aurora, and Zambales in Central Luzon and the island of Mindoro.

Central Bikol, commonly called Bikol Naga or simply as Bikol, is an Austronesian language spoken by the Bicolanos, primarily in the Bicol Region of southern Luzon, Philippines. It is spoken in the northern and western part of Camarines Sur, second congressional district of Camarines Norte, eastern part of Albay, northeastern part of Sorsogon, San Pascual town in Masbate, and southwestern part of Catanduanes. Central Bikol speakers can be found in all provinces of Bicol and it is a majority language in Camarines Sur. The standard sprachraum form is based on the Canaman dialect.

Bernardo Carpio is a legendary figure in Philippine mythology who is said to be the cause of earthquakes. There are numerous versions of this tale. Some versions say Bernardo Carpio is a giant, as supported by the enormous footsteps he has reputedly left behind in the mountains of Montalban. Others say he was the size of an ordinary man. Accounts of the stories have pre-colonial origins, but the name of the hero was Hispanized during the Spanish colonization. The original name of the hero has been lost in time. All versions of the story agree that Bernardo Carpio had a strength that was similar to that of many strong men-heroes in Asian epics, such as Lam-ang.

Agimat, also known as anting or folklorized as anting-anting, is a Filipino word for "amulet" or "charm". Anting-anting is also a Filipino system of magic and sorcery with special use of the above-mentioned talismans, amulets, and charms. Other general terms for agimat include virtud (Virtue) and galing (Prowess).

Rinconada Bikol or simply Rinconada, spoken in the province of Camarines Sur, Philippines, is one of several languages that compose the Inland Bikol group of the Bikol macrolanguage. It belongs to the Austronesian language family that also includes most Philippine languages, the Formosan languages of Taiwanese aborigines, Malay, the Polynesian languages and Malagasy.

In Philippine mythology, the Tigmamanukan was believed by the Tagalog people to be an omen or augural bird. Although the behaviors of numerous birds and lizards were said to be omens, particular attention was paid to the tigmamanukan. Before Christianisation, the Tagalogs believed that the tigmamanukan was sent by Bathala to give hints to mankind whether they needed to proceed on a journey or not. In some Philippine creation myths, the tigmamanukan bird was sent by Bathala to crack open the primordial bamboo whence the first man and woman came out.

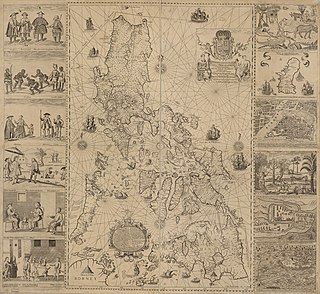

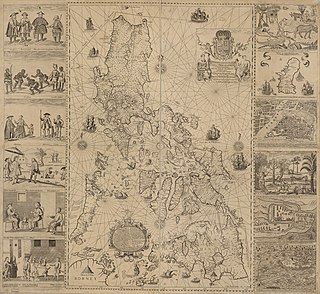

In Philippine history, the Tagalog bayan of Maynila was one of the most cosmopolitan of the early historic settlements on the Philippine archipelago. Fortified with a wooden palisade which was appropriate for the predominant battle tactics of its time, it lay on the southern part of the Pasig River delta, where the district of Intramuros in Manila currently stands, and across the river from the separately-led Tondo polity.

The Bahala Na Gang (BNG) is a street gang founded in the Philippines which subsequently spread to the United States.

Kamayan is a Filipino cultural term for the various occasions or contexts in which pagkakamay is practiced, including as part of communal feasting. Such feasts traditionally served the food on large leaves such as banana or breadfruit spread on a table, with the diners eating from their own plates. The practice is also known as kinamot or kinamut in Visayan languages.

In the Philippine languages, a system of titles and honorifics was used extensively during the pre-colonial era, mostly by the Tagalogs and Visayans. These were borrowed from the Malay system of honorifics obtained from the Moro peoples of Mindanao, which in turn was based on the Indianized Sanskrit honorifics system and the Chinese's used in areas like Ma-i (Mindoro) and Pangasinan. The titles of historical figures such as Rajah Sulayman, Lakandula and Dayang Kalangitan evidence Indian influence. Malay titles are still used by the royal houses of Sulu, Maguindanao, Maranao and Iranun on the southern Philippine island of Mindanao. However, these are retained on a traditional basis as the 1987 Constitution explicitly reaffirms the abolition of royal and noble titles in the republic.

Tagalog profanity can refer to a wide range of offensive, blasphemous, and taboo words or expressions in the Tagalog language of the Philippines. Due to Filipino culture, expressions which may sound benign when translated back to English can cause great offense; while some expressions English speakers might take great offense to can sound benign to a Tagalog speaker. Filipino, the national language of the Philippines, is the standard register of Tagalog, so as such the terms Filipino profanity and Filipino swear words are sometimes also employed.

The indigenous religious beliefs of the Tagalog people were well documented by Spanish missionaries, mostly in the form of epistolary accounts (relaciones) and entries in various dictionaries compiled by missionary friars.