Palawan, officially the Province of Palawan, is an archipelagic province of the Philippines that is located in the region of Mimaropa. It is the largest province in the country in terms of total area of 14,649.73 km2 (5,656.29 sq mi). The capital and largest city is Puerto Princesa wherein it is geographically grouped but administered independently from the province. Palawan is known as the Philippines' Last Frontier and as the Philippines' Best Island.

Aeta, Agta and Dumagat, are collective terms for several indigenous Filipinos who live in various parts of the island of Luzon in the Philippines. They are also known as "Philippines Negrito", and included in the wider Negrito grouping of Southeast Asia, with whom they share superficial common physical characteristics such as dark skin tones, short statures, frizzy to curly-hair, and a higher frequency of naturally lighter hair colour (blondism) relative to the general population. They are thought to be among the earliest inhabitants of the Philippines, preceding the Austronesian migrations. Regardless, modern Aeta populations have significant Austronesian admixture and speak Austronesian languages.

Philippine mythology is rooted in the many indigenous Philippine folk religions. Philippine mythology exhibits influence from Indonesian, Hindu, Muslim, Shinto, Buddhist, and Christian traditions.

Cordyline fruticosa is an evergreen flowering plant in the family Asparagaceae. The plant is of great cultural importance to the traditional animistic religions of Austronesian and Papuan peoples of the Pacific Islands, New Zealand, Island Southeast Asia, and Papua New Guinea. It is also cultivated for food, traditional medicine, and as an ornamental for its variously colored leaves. It is identified by a wide variety of common names, including ti plant, palm lily, cabbage palm.

Filipino shamans, commonly known as babaylan, were shamans of the various ethnic groups of the pre-colonial Philippine islands. These shamans specialized in communicating, appeasing, or harnessing the spirits of the dead and the spirits of nature. They were almost always women or feminized men. They were believed to have spirit guides, by which they could contact and interact with the spirits and deities and the spirit world. Their primary role were as mediums during pag-anito séance rituals. There were also various subtypes of babaylan specializing in the arts of healing and herbalism, divination, and sorcery.

Indigenous Philippine folk religions are the distinct native religions of various ethnic groups in the Philippines, where most follow belief systems in line with animism. Generally, these indigenous folk religions are referred to as Anito or Anitism or the more modern and less ethnocentric Dayawism, where a set of local worship traditions are devoted to the anito or diwata, terms which translate to gods, spirits, and ancestors. 0.23% of the population of the Philippines are affiliated with the indigenous Philippine folk religions according to the 2020 national census, an increase from the previous 0.19% from the 2010 census.

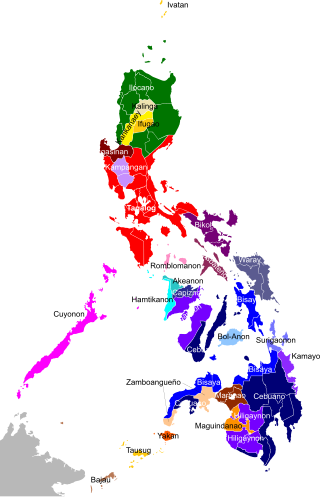

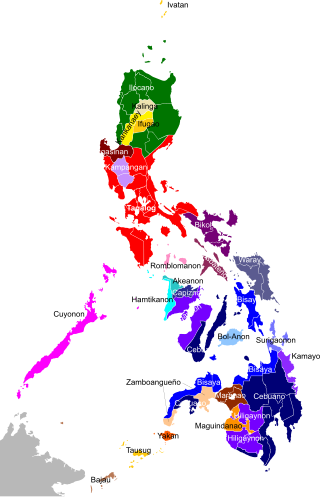

The Philippines is inhabited by more than 182 ethnolinguistic groups, many of which are classified as "Indigenous Peoples" under the country's Indigenous Peoples' Rights Act of 1997. Traditionally-Muslim peoples from the southernmost island group of Mindanao are usually categorized together as Moro peoples, whether they are classified as Indigenous peoples or not. About 142 are classified as non-Muslim Indigenous People groups, and about 19 ethnolinguistic groups are classified as neither indigenous nor moro. Various migrant groups have also had a significant presence throughout the country's history.

The Sambal people are a Filipino ethnolinguistic group living primarily in the province of Zambales and the Pangasinense municipalities of Bolinao and Anda. The term may also refer to the general inhabitants of Zambales. They were also referred to as the Zambales during the Spanish colonial era.

Palawan, the largest province in the Philippines, is home to several indigenous ethnolinguistic groups namely, the Kagayanen, Tagbanwa, Palawano, Taaw't Bato, Molbog, and Batak tribes. They live in remote villages in the mountains and coastal areas.

The Puerto Princesa Subterranean River National Park is a protected area in the Philippines.

The Tagbanwa people are one of the oldest ethnic groups in the Philippines, and can be mainly found in the central and northern Palawan. Research has shown that the Tagbanwa are possible descendants of the Tabon Man, thus making them one of the original inhabitants of the Philippines. They are a brown-skinned, slim, and straight-haired ethnic group.

Cuyunon refers to an ethnic group populating the Cuyo Islands, along with northern and central Palawan. The Cuyunons hail originally from Cuyo and the surrounding Cuyo Islands, a group of islands and islets in the northern Sulu Sea, to the north east of Palawan. They are considered an elite class among the hierarchy of native Palaweños. They are part of the wider Visayan ethnolinguistic group, who constitute the largest Filipino ethnolinguistic group.

The indigenous religious beliefs of the Tagbanwa people includes the religious beliefs, mythology and superstitions that has shaped the Tagbanwa way of life. It shares certain similarities with that of other ethnic groups in the Philippines, such as in the belief in heaven, hell and the human soul.

The Subanon is an indigenous group to the Zamboanga peninsula area, particularly living in the mountainous areas of Zamboanga del Sur and Misamis Occidental, Mindanao Island, Philippines. The Subanon people speak Subanon languages. The name is derived from the word soba or suba, a word common in Sulu, Visayas, and Mindanao, which means "river", and the suffix -nun or -non, which indicates a locality or place of origin. Accordingly, the name Subanon means "a person or people of the river". These people originally lived in the low-lying areas. However, due to disturbances and competitions from other settlers like the Moros, and migrations of Cebuano speakers and individuals from Luzon and other parts of Visayas to the coastal areas attracted by the inviting land tenure laws, further pushed the Subanon into the interior.

The Palawan people, also known as the Palaw'an or Palawano, are an ethnic group native to the Palawan group of islands in the Philippines.

The Teduray, also called Tiruray or Tirurai, are a Filipino ethnic group. They speak the Tiruray language. Their name may have come from words tew, meaning people, and duray, referring to a small bamboo hook and a line used for fishing.

Ancient diet is mainly determined by food's accessibility which involves location, geography and climate while ancient health is affected by food consumption apart from external factors such as diseases and plagues. There are still a lot of doubt about this ancient diet due to lack of evidence. Similar to what anthropologist Amanda Henry has said, there are a lot of time periods in the human history but there are only theories to answer questions on what people actually ate then. Only recently have traces been discovered in what was left of these people.

Anito, also spelled anitu, refers to ancestor spirits, nature spirits, and deities in the indigenous Philippine folk religions from the precolonial age to the present, although the term itself may have other meanings and associations depending on the Filipino ethnic group. It can also refer to carved humanoid figures, the taotao, made of wood, stone, or ivory, that represent these spirits. Anito is also sometimes known as diwata in certain ethnic groups.