The Batavi were an ancient Germanic tribe that lived around the modern Dutch Rhine delta in the area that the Romans called Batavia, from the second half of the first century BC to the third century AD. The name is also applied to several military units employed by the Romans that were originally raised among the Batavi. The tribal name, probably a derivation from batawjō, refers to the region's fertility, today known as the fruitbasket of the Netherlands.

Valens was Roman emperor from 364 to 378. Following a largely unremarkable military career, he was named co-emperor by his elder brother Valentinian I, who gave him the eastern half of the Roman Empire to rule. In 378, Valens was defeated and killed at the Battle of Adrianople against the invading Goths, which astonished contemporaries and marked the beginning of barbarian encroachment into Roman territory.

Batavia is a historical and geographical region in the Netherlands, forming large fertile islands in the river delta formed by the waters of the Rhine and Meuse rivers. During the Roman empire, it was an important frontier region and source of imperial soldiers. Its name is possibly pre-Roman.

The Battle of Adrianople, sometimes known as the Battle of Hadrianopolis, was fought between an Eastern Roman army led by the Eastern Roman Emperor Valens and Gothic rebels led by Fritigern. The battle took place in the vicinity of Adrianople, in the Roman province of Thracia. It ended with an overwhelming victory for the Goths and the death of Emperor Valens.

Valentinian I, sometimes called Valentinian the Great, was Roman emperor from 364 to 375. He ruled the Western half of the empire, while his brother Valens ruled the East. During his reign, he fought successfully against the Alamanni, Quadi, and Sarmatians, strengthening the border fortifications and conducting campaigns across the Rhine and Danube. His general Theodosius defeated a revolt in Africa and the Great Conspiracy, a coordinated assault on Roman Britain by Picts, Scoti, and Saxons. Valentinian founded the Valentinianic dynasty, with his sons Gratian and Valentinian II succeeding him in the western half of the empire.

The Revolt of the Batavi took place in the Roman province of Germania Inferior between AD 69 and 70. It was an uprising against the Roman Empire started by the Batavi, a small but militarily powerful Germanic tribe that inhabited Batavia, on the delta of the river Rhine. They were soon joined by the Celtic tribes from Gallia Belgica and some Germanic tribes.

This is a chronology of warfare between the Romans and various Germanic peoples. The nature of these wars varied through time between Roman conquest, Germanic uprisings, later Germanic invasions of the Western Roman Empire that started in the late second century BC, and more. The series of conflicts was one factor which led to the ultimate downfall of the Western Roman Empire in particular and ancient Rome in general in 476.

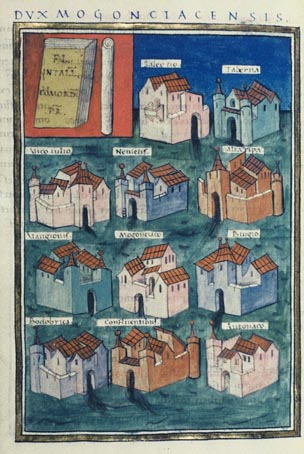

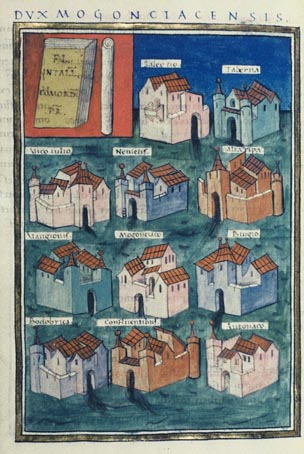

The Vangiones appear first in history as an ancient Germanic tribe of unknown provenance. They threw in their lot with Ariovistus in his bid of 58 BC to invade Gaul through the Doubs river valley and lost to Julius Caesar in a battle probably near Belfort. After some Celts evacuated the region in fear of the Suebi, the Vangiones, who had made a Roman peace, were allowed to settle among the Mediomatrici in northern Alsace.. They gradually assumed control of the Celtic city of Burbetomagus, later Worms.

The Great Conspiracy was a year-long state of war and disorder that occurred near the end of Roman Britain. The historian Ammianus Marcellinus described it as a barbarica conspiratio, which took advantage of a depleted military force in the province; many soldiers had marched with Magnentius in his unsuccessful bid to become emperor. Few returned, and supply, pay, and discipline in the following years may have been deficient.

The Mattiaci were by Tacitus recorded as an ancient Germanic tribe and related to the Chatti, their Germanic neighbors to the east. There is no clear definition of what the tribe's name meant. The Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography suggests that the name is derived from a combination of 'matte', meaning 'a meadow', and 'ach', signifying water or a bath.

Petulantes was an auxilia palatina of the Late Roman army.

The Frisiavones were a Germanic people living near the northern border of Gallia Belgica during the early first millennium AD. Little is known about them, but they appear to have resided in the area of what is today the southern Netherlands, possibly in two distinct regions, one in the islands of the river deltas of Holland, and one to the southeast of it.

The Heruli was an auxilia palatina unit of the Late Roman army, active between the 4th and the 5th century. It was composed of 500 soldiers and was the heir of those ethnic groups that were initially used as auxiliary units of the Roman army and later integrated in the Roman Empire after the Constitutio Antoniniana. Their name was derived from the people of the Heruli. In the sources they are usually recorded together with the Batavi, and it is probable the two units fought together. At the beginning of the 5th century two related units are attested, the Heruli seniores in the West and the Heruli iuniores in the East.

For around 450 years, from around 55 BC to around 410 AD, the southern part of the Netherlands was integrated into the Roman Empire. During this time the Romans in the Netherlands had an enormous influence on the lives and culture of the people who lived in the Netherlands at the time and (indirectly) on the generations that followed.

The Cugerni were a Germanic tribal grouping with a particular territory within the Roman province of Germania Inferior, which later became Germania Secunda. More precisely they lived near modern Xanten, and the old Castra Vetera, on the Rhine. This part of Germania Secunda was called the Civitas or Colonia Traiana, and it was also inhabited by the Betasii.

The Germani cisrhenani, or "Left bank Germani", were a group of Germanic peoples who lived west of the Lower Rhine at the time of the Gallic Wars in the mid-1st century BC.

Flavius Arintheus was a Roman army officer who started his career in the middle ranks and rose to senior political and military positions. He served the emperors Constantius II, Julian, Jovian and Valens. In 372 he was appointed consul, alongside Domitius Modestus.

The Numerus Batavorum, also called the cohors Germanorum, Germani corporis custodes, Germani corpore custodes, Imperial German Bodyguard or Germanic bodyguard was a personal, imperial guards unit for the Roman emperors of the Julio-Claudian dynasty composed of Germanic soldiers. Although the Praetorians may be considered the Roman emperor's main bodyguard, the Germanic bodyguards were a unit of more personal guards recruited from distant parts of the Empire, so they had no political or personal connections with Rome or the provinces.

Dagalaifus was a Roman army officer of Germanic descent. A pagan, he served as consul in 366. In the year 361, he was appointed by Emperor Julian as comes domesticorum. He accompanied Julian on his march through Illyricum to quell what remained of the government of Constantius II that year. He led a party into Sirmium that arrested the commander of the resisting army, Lucillianus. In the spring of 363, Dagalaifus was part of Julian's ultimately-disastrous invasion of Persia. On June 26, while still campaigning, Julian was killed in a skirmish. Dagalaifus, who had been with the rear guard, played an important role in the election of the next emperor. The council of military officers finally agreed on the new comes domesticorum, Jovian, to succeed Julian. Jovian was a Christian whose father Varronianus had himself once served as comes domesticorum.

Hercules Magusanus is a Romano-Germanic deity or hero worshipped during the early first millennium AD in the Lower Rhine region among the Batavi, Marsaci, Ubii, Cugerni, Baetasii, and probably among the Tungri.