The American Civil War was a civil war in the United States between the Union and the Confederacy, which had been formed by states that had seceded from the Union.

Jefferson F. Davis was an American politician who served as the first and only president of the Confederate States from 1861 to 1865. He represented Mississippi in the United States Senate and the House of Representatives as a member of the Democratic Party before the American Civil War. He was the United States Secretary of War from 1853 to 1857.

The Compromise of 1850 was a package of five separate bills passed by the United States Congress in September 1850 that temporarily defused tensions between slave and free states in the years leading up to the American Civil War. Designed by Whig senator Henry Clay and Democratic senator Stephen A. Douglas, with the support of President Millard Fillmore, the compromise centered on how to handle slavery in recently acquired territories from the Mexican–American War (1846–48).

The Confederate States Army, also called the Confederate Army or the Southern Army, was the military land force of the Confederate States of America during the American Civil War (1861–1865), fighting against the United States forces to win the independence of the Southern states and uphold and expand the institution of slavery. On February 28, 1861, the Provisional Confederate Congress established a provisional volunteer army and gave control over military operations and authority for mustering state forces and volunteers to the newly chosen Confederate president, Jefferson Davis. Davis was a graduate of the U.S. Military Academy, and colonel of a volunteer regiment during the Mexican–American War. He had also been a United States senator from Mississippi and U.S. Secretary of War under President Franklin Pierce. On March 1, 1861, on behalf of the Confederate government, Davis assumed control of the military situation at Charleston, South Carolina, where South Carolina state militia besieged Fort Sumter in Charleston harbor, held by a small U.S. Army garrison. By March 1861, the Provisional Confederate Congress expanded the provisional forces and established a more permanent Confederate States Army.

Comer Vann Woodward was an American historian who focused primarily on the American South and race relations. He was long a supporter of the approach of Charles A. Beard, stressing the influence of unseen economic motivations in politics.

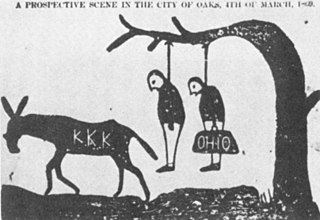

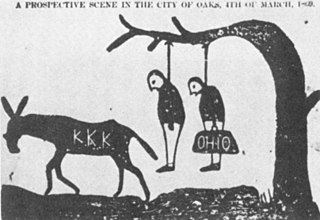

In United States history, the pejorative scalawag referred to white Southerners who supported Reconstruction policies and efforts after the conclusion of the American Civil War.

James Munro McPherson is an American historian specializing in the American Civil War. He is the George Henry Davis '86 Professor Emeritus of United States History at Princeton University. He received the 1989 Pulitzer Prize for Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era. McPherson was the president of the American Historical Association in 2003.

Neo-Confederates are groups and individuals who portray the Confederate States of America and its actions during the American Civil War in a positive light. The League of the South, the Sons of Confederate Veterans and other neo-Confederate organizations continue to defend the secession of the former Confederate States.

The most common name for the American Civil War in modern American usage is simply "The Civil War". Although rarely used during the war, the term "War Between the States" became widespread afterward in the Southern United States. During and immediately after the war, Northern historians often used the terms "War of the Rebellion" and "Great Rebellion", and the Confederate term was "War for Southern Independence", which regained some currency in the 20th century but has again fallen out of use. The name "Slaveholders' Rebellion" was used by Frederick Douglass and appears in newspaper articles. "Freedom War" is used to celebrate the war's effect of ending slavery.

James Shepherd Pike was an American journalist and a historian of South Carolina during the Reconstruction Era.

David Morris Potter was an American historian specializing in the study of the coming of the American Civil War, especially the political factors. His best known book is The Impending Crisis, 1848–1861, which was completed and edited by Don E. Fehrenbacher and published posthumously in 1976.

The Oxford History of the United States is an ongoing multivolume narrative history of the United States published by Oxford University Press. Conceived in the 1950s and launched in 1961 under the co-editorship of historians Richard Hofstadter and C. Vann Woodward, the series has been edited by David M. Kennedy since 1999.

The American state of Virginia became a prominent part of the Confederacy when it joined during the American Civil War. As a Southern slave-holding state, Virginia held the state convention to deal with the secession crisis and voted against secession on April 4, 1861. Opinion shifted after the Battle of Fort Sumter on April 12, and April 15, when U.S. President Abraham Lincoln called for troops from all states still in the Union to put down the rebellion. For all practical purposes, Virginia joined the Confederacy on April 17, though secession was not officially ratified until May 23. A Unionist government was established in Wheeling and the new state of West Virginia was created by an act of Congress from 50 counties of western Virginia, making it the only state to lose territory as a consequence of the war. Unionism was indeed strong also in other parts of the State, and during the war the Restored Government of Virginia was created as rival to the Confederate Government of Virginia, making it one of the states to have 2 governments during the Civil War.

This is a selected bibliography of the main scholarly books and articles of Reconstruction, the period after the American Civil War, 1863–1877.

In the United States, Southern Unionists were white Southerners living in the Confederate States of America opposed to secession. Many fought for the Union during the Civil War. These people are also referred to as Southern Loyalists, Union Loyalists, or Lincoln's Loyalists. Pro-Confederates in the South derided them as "Tories". During Reconstruction, these terms were replaced by "scalawag", which covered all Southern whites who supported the Republican Party.

Historiography examines how the past has been viewed or interpreted. Historiographic issues about the American Civil War include the name of the war, the origins or causes of the war, and President Abraham Lincoln's views and goals regarding slavery.

Virginia v. West Virginia, 78 U.S. 39 (1871), is a 6-3 ruling by the Supreme Court of the United States that held that if a governor has discretion in the conduct of the election, the legislature is bound by his action and cannot undo the results based on fraud. The Court implicitly affirmed that the breakaway Virginia counties had received the necessary consent of both the Commonwealth of Virginia and the United States Congress to become a separate U.S. state. The Court also explicitly held that Berkeley County and Jefferson County were part of the new State of West Virginia.

This timeline of events leading to the American Civil War is a chronologically ordered list of events and issues that historians recognize as origins and causes of the American Civil War. These events are roughly divided into two periods: the first encompasses the gradual build-up over many decades of the numerous social, economic, and political issues that ultimately contributed to the war's outbreak, and the second encompasses the five-month span following the election of Abraham Lincoln as President of the United States in 1860 and culminating in the capture of Fort Sumter in April 1861.

Daniel Harris Reynolds was a Confederate States Army brigadier general during the American Civil War. He was born at Centerburg, Ohio, but moved to Iowa, Tennessee, and finally to Arkansas before the Civil War. He was a lawyer in Arkansas before the war. After the war, Reynolds resumed his practice of law and was a member of the Arkansas Senate for one term.

White Southerners, are White Americans from the Southern United States, originating from the various waves of Northwestern European immigration to the region beginning in the 17th century. A semi-uniform white Southern identity coalesced during the Reconstruction era partially to enforce white supremacism in the region.