21st Division and 24th Division

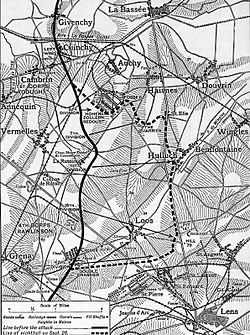

The general reserve was prepared for the battle north and south of Lillers. It consisted of the Cavalry Corps (1st, 2nd and 3rd Cavalry Divisions) and the XI Corps (Guards Division, 21st Division and 24th Division), which marched to the area from the divisional concentration areas west of St Omer. XI Corps began its advance on 20th September, with the 21st Division marching from its billets north-west of St Omer via Aire and the 24th Division from billets south-west of St Omer. The Guards Division followed in several columns a day later. The movement was carried out at night to avoid enemy aircraft observation, with troops resting in billets during the day. On the first two nights, over 20 mi (32 km) were covered and the Guards Division was billeted west of the town. The 3rd Cavalry Division, allotted to the First Army as Army cavalry, moved to the Bois des Dames, while the rest of the Cavalry Corps was concentrated around Therouanne.

Marching orders did not reach XI Corps until 2:00 a.m and both divisions did not reach their final position for the night until even later. The 21 Division battalions detached to the 15th (Scottish) Division, arrived in the battle area after being informed of their presence at Hill 70. Brigadier General Wilkinson sent two battalions to reinforce. The 8th Battalion East Yorkshire Regiment and 10th Battalion Green Howards marched down the Lens road, crossing the old British front line. They were bombarded by German artillery in St Pierre, resulting in casualties and destruction of their transport.

Two battalions intended to attack Hill 70, were disorientated and moved instead south of Loos village. They encountered machine-gun fire from Chalk Pit Copse and British troops in Loos Cemetery. The 12th and 13th battalions of the 62nd Brigade, along with Brigade HQ, arrived in Loos village. Brigadier General Wilkinson sent one company of the 12 Northumberland to Hill 70, which was assumed to be a general relief. The two battalions on the hill, the 9th Black Watch and 10th Gordon Highlanders, withdrew, leaving the Northumberland company the only British troops on the approaches. The last battalion of the 62nd Brigade, the 13th Northumberland, was sent to assist the 46th Brigade, where some units assumed a general relief and began to withdraw. Control on the 15th (Scottish) Division front was lost during the night and the line reached during the day was much weaker than it should have been.

During the night the Germans launched two counter-attacks on the 7th Royal Scots Fusiliers, one of the battalions of the 45th Brigade that the commander of the 15th (Scottish) Division had deployed to hold Loos after his other two brigades had taken it. Both were beaten off. The situation around Loos and Hill 70 and the right flank of First Army did not change very much throughout the night. This was not so elsewhere on the British front. The 73rd Brigade, 9th (Scottish) Division, assembled in the original British front line and relieved the 26th Brigade at Fosse 8, crossing German trench lines in failing light and rain. The relief was delayed until the Germans counter-attack on 26 September but the fosse was held. A methodical counter-attack by a reinforced German division pushed the British back into the German Gun Trench, capturing The Quarries and Brigadier General Bruce. The British managed to halt further progress but had to establish a line 500 yd (460 m) back.

Before the general advance could begin hill 70 had to be retaken. General Rawlinson, allocated the task to the 15th (Scottish) Division, with zero hour at 9:00 a.m. after an hour-long bombardment. The commander of the 15th (Scottish) Division in turn gave the job to the 45 th Brigade and the 62nd Brigade (on loan from the 21st Division) the orders arriving at both brigade headquarters at around 5:00 a.m. on 26 September. After the artillery bombardment ended the 45th Brigade would make an attack astride the track which ran just south of east from Loos to the La Bassée–Lens road, followed up by the 62nd Brigade. Once Hill 70 and its redoubt had been taken, the troops would be responsible for digging in and facing south and south-east to prevent any interference with the attack to its north.

The artillery plan to support the attack included two field batteries and two howitzer batteries which had come forward during the night and were now at the cemetery just west of Loos. Due to severe delays, the battalion commanders received their instructions at around 8:00 a.m. After the artillery bombardment, the three battalions of the 45th Brigade moved forward, despite casualties on the approach. They managed to kill some German defenders and drive more out and back towards their second line. The attackers were unable to force the defenders out of the central part of the redoubt, leading to increased German artillery and mortar fire from St Auguste, St Emile and Hill 70. As the toll of dead and injured attackers increased, the survivors of the 45th Brigade were forced to abandon the redoubt and fall back to the western slopes.

The 12th Northumberland Fusiliers and 10th Green Howards of the 62nd Brigade, following up 200 yd (180 m) behind the 45th Brigade, had problems caused by bad light and inadequate maps and diverged to the right and began to attack Loos Crassier. Once the error was realised the commanding officers regained direction and the two battalions reached the ridge and swept over it, either side of the Hill 70 Redoubt. They still could not take the redoubt, and they were soon driven back to the western slopes.

The attempt to neutralise Hill 70 before the main attack had failed but Haking decided to press on. He thought that the main attack on the German second line would perforce outflank Hill 70, which would be rendered useless. Phase Two of the operation required the attacking infantry of the 21st division and the 24th Divisions on a frontage of just under 1 mi (1.6 km) to ascend a gently rising slope for about 1,000 yd (910 m) when they would come upon the German second line of defence consisting of only one trench, without the usual support or reserve lines but it was strongly held and well protected. Reinforcements had arrived during the night and they had thrown up a barbed wire entanglement 4 ft (1.2 m) high × 20 ft (6.1 m) deep. There would be a preliminary artillery bombardment lasting an hour.

During the night, the artillery struggled to advance beyond the western side of Le Rutoir, causing the guns to be visible to the Germans. Despite attempts to camouflage them, the Germans could bring down counter-battery fire from their artillery and receive infantry rifle fire. The bombardment was less effective than planned and little damage was done to the German trench before infantry advanced. During the final preparations for the attack, the Germans counter-attacked Bois Hugo, causing chaos for the British. The 12th Battalion, West Yorkshire Regiment, broke and ran back, leading to the death of Brigadier General Nickalls. A battalion from the 64th Brigade opened fire on the retreating British soldiers but the fourth battalion held their ground and shot down the advancing German troops.

At 11:00 a.m., two battalions of the 24th Division moved across the La Bassée–Lens road, reaching their objectives quickly. The German survivors were driven off, helping to steady the troops of the 21st Division. The attack on Hulluch, was uncoordinated and half-hearted, failing to capture or mask it. The divisional frontage was filled with gaps and the six battalions of the division were left with survivors only 50 yd (46 m) from the Germans second line. The German second line was protected by wire and the infantry suffered from artillery bombardment. The advance was stopped due to fire from both sides. On the right, the 21st Division faced worse conditions, with orders not reaching some battalions until Zero Hour. The division had already suffered many losses capturing Hill 70 and repelling the German counter-attack. The few soldiers who managed to get near the German line were unable to pass through the wire.

On the 24th Division front, no advance was possible due to the troops being isolated in front of the German trench. Both divisions retreated to the Grenay–Hulluch road and the old German front line, where a few officers and senior NCOs rallied the remnants of the two divisions. Despite the Germans re-occupying Hill 70 and the redoubt, the 15th (Scottish) Division was dug in on the western slopes. As casualties increased, ammunition ran short and supplies could not be got forward. At 1:00 p.m. troops on Hill 70 began to retreat towards Loos. Communication had broken down and battalions debated whether to retire to the old German trenches or give up Loos. The 7th Royal Scots Fusiliers remained east of Loos until they were the only battalion on the approaches to Hill 70. They met the 6th Cavalry Brigade, who had instructions to take any 15th (Scottish) Division troops in Loos. The 3rd Dragoon Guards and 1st Royal Dragoons were equivalent to one infantry battalion but managed to rally many of the 15th (Scottish) Division troops, reoccupying the trenches on Hill 70 by 8:00 p.m.

Guards Division

When the news of what was happening to the 21st Division and the 24th Division was brought home to the Army Commander, there was only the Guards Division as reserve available to him. Earlier in the morning, when the attempt to capture Hill 70 had failed, Haking had ordered the Guards Division to move to positions between Le Rutoir−Loos and Vermelles−Hulluch roads. Traffic chaos delayed the order, causing trouble for the 21st Division and the 24th Division. Haking sent another order to the Guards to continue to the old German front line and strengthen their position. Congested roads, desultory German shelling and battlefield confusion delayed the arrival of the Guards at the British jumping-off line until 6:00 p.m. The Guards began to reverse the captured German trenches. Major General Earl of Cavan sent orders to the Guards Division to relieve the 21st Division and the 24th Division during the night. The Guards took up their new position, allowing the remnants of the two New Army divisions to be withdrawn. By 6:00 a.m. on 27 September, the 1st Guards Brigade had the 3rd Coldstream on the left, the 1st Division, and the 2nd Coldstream on its right, covering a frontage of 1,400 yd (1,300 m) from Hulluch to Lone Tree. The brigade's sector ran south-west for 1,800 yd (1,600 m) to Fort Glatz, a redoubt on the old German Loos defences.

The Guards were to consolidate the British line to renew the attack. Orders were given to Haking and Cavan, who ordered the Guards Division to attack and capture the Chalk Pits, Puits 14 and Hill 70. The Germans counter-attacked Fosse 8 and The Dump, recapturing them. The Guards would have needed the support of their own artillery and the 21st Division and the 24th Division artilleries. There was insufficient ammunition and the bombardment was sparse. The news of the loss of the Dump and Fosse 8 further undermined the British offensive. The brigade commander decided to abandon the Dump and Fosse trenches and establish a new line east of the Hohenzollern Redoubt. Major-General George Thesiger, commander of the 9th (Scottish) Division, was killed while assessing the situation. The 28th Division moved to the battle area but too late to save Fosse 8. Major General Butler informed Haig, who ordered the attack to be cancelled.

On the left, the 2nd Guards Brigade, led by the 2nd Irish Guards and supported by the 1st Coldstream, attacked the Chalk Pit, while the 1st Scots Guards attacked to capture Puits 14, with the 3rd Grenadier Guards in reserve. The Chalk Pit was quickly seized but the advance on Puits 14 faced massed machine-gun fire. Despite reinforcements, including the 4th Grenadier Guards, the Scots Guards suffered severe casualties and could not hold the position. A temporary firing line was established from the Chalk Pit to Loos. Cavan ordered the 3rd Guards Brigade to delay its assault on Hill 70 until Puits 14 was secured but Brigadier General Frederick Heyworth mistakenly assumed Puits 14 had been captured due to a brief British occupation.

The 4th Grenadier Guards, 1st Welsh Guards, 2nd Scots Guards, and 1st Grenadier Guards of the 4th Brigade advanced through Loos under severe artillery fire. As confusion from gas shells disrupted their movement, two companies of the 4th Grenadiers joined the 2nd Brigade at Puits 14 by mistake. At 5:30 p.m., the 1st Welsh Guards attacked Hill 70 but were stopped at the crest under machine-gun fire from Puits 14 and the hill's redoubt. Despite their efforts, the Welsh and Grenadiers could not capture the position. By nightfall, the British line had strengthened, securing Loos and linking with cavalry on the right and the Loos–Hulluch Road on the left. The 47th (1/2nd London) Division captured Chalk Pit Copse, while a 7th Division counter-attack on The Quarries was a costly failure. Later attacks, including one led by the 2nd Worcester, also fell short, General Capper being killed during the assault. On the night of 27 September, Cavan and his brigade commanders agreed that further attempts on Hill 70 would be futile, though the First Army insisted on attacking Puits 14 again. French, noting the lack of reserves and vulnerability of the British right flank, coordinated with General Joffre and General Foch for French forces to relieve the 47th (1/2nd London) Division and strengthen the line. French told Foch on 28 September, that a gap could be "rushed" just north of Hill 70, although Foch felt that this would be difficult to co-ordinate and Haig told him that the First Army was in no position for further attacks. A lull fell on 28 September, with the British back on their start lines.