Argo Navis, or simply Argo, is one of Ptolemy's 48 constellations, now a grouping of three IAU constellations. It is formerly a single large constellation in the southern sky. The genitive is "Argus Navis", abbreviated "Arg". John Flamsteed and other early modern astronomers called it Navis, genitive "Navis", abbreviated "Nav".

Caelum is a faint constellation in the southern sky, introduced in the 1750s by Nicolas Louis de Lacaille and counted among the 88 modern constellations. Its name means "chisel" in Latin, and it was formerly known as Caelum Sculptorium ; it is a rare word, unrelated to the far more common Latin caelum, meaning "sky", "heaven", or "atmosphere". It is the eighth-smallest constellation, and subtends a solid angle of around 0.038 steradians, just less than that of Corona Australis.

A Flamsteed designation is a combination of a number and constellation name that uniquely identifies most naked eye stars in the modern constellations visible from southern England. They are named for John Flamsteed who first used them while compiling his Historia Coelestis Britannica.

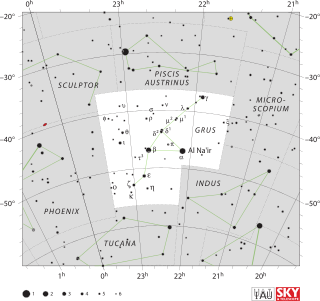

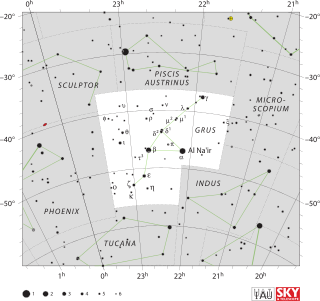

Grus is a constellation in the southern sky. Its name is Latin for the crane, a type of bird. It is one of twelve constellations conceived by Petrus Plancius from the observations of Pieter Dirkszoon Keyser and Frederick de Houtman. Grus first appeared on a 35-centimetre-diameter (14-inch) celestial globe published in 1598 in Amsterdam by Plancius and Jodocus Hondius and was depicted in Johann Bayer's star atlas Uranometria of 1603. French explorer and astronomer Nicolas-Louis de Lacaille gave Bayer designations to its stars in 1756, some of which had been previously considered part of the neighbouring constellation Piscis Austrinus. The constellations Grus, Pavo, Phoenix and Tucana are collectively known as the "Southern Birds".

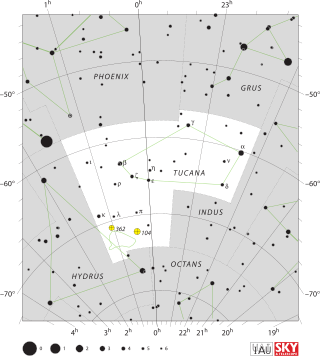

Hydrus is a small constellation in the deep southern sky. It was one of twelve constellations created by Petrus Plancius from the observations of Pieter Dirkszoon Keyser and Frederick de Houtman and it first appeared on a 35-cm (14 in) diameter celestial globe published in late 1597 in Amsterdam by Plancius and Jodocus Hondius. The first depiction of this constellation in a celestial atlas was in Johann Bayer's Uranometria of 1603. The French explorer and astronomer Nicolas Louis de Lacaille charted the brighter stars and gave their Bayer designations in 1756. Its name means "male water snake", as opposed to Hydra, a much larger constellation that represents a female water snake. It remains below the horizon for most Northern Hemisphere observers.

Piscis Austrinus is a constellation in the southern celestial hemisphere. The name is Latin for "the southern fish", in contrast with the larger constellation Pisces, which represents a pair of fish. Before the 20th century, it was also known as Piscis Notius. Piscis Austrinus was one of the 48 constellations listed by the 2nd-century astronomer Ptolemy, and it remains one of the 88 modern constellations. The stars of the modern constellation Grus once formed the "tail" of Piscis Austrinus. In 1597, Petrus Plancius carved out a separate constellation and named it after the crane.

Sextans is a faint, minor constellation on the celestial equator which was introduced in 1687 by Polish astronomer Johannes Hevelius. Its name is Latin for the astronomical sextant, an instrument that Hevelius made frequent use of in his observations.

In astronomy, stars have a variety of different stellar designations and names, including catalogue designations, current and historical proper names, and foreign language names.

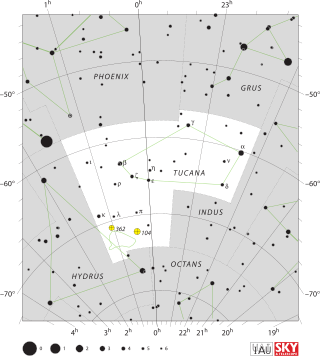

Tucana is a constellation in the southern sky, named after the toucan, a South American bird. It is one of twelve constellations conceived in the late sixteenth century by Petrus Plancius from the observations of Pieter Dirkszoon Keyser and Frederick de Houtman. Tucana first appeared on a 35-centimetre-diameter (14 in) celestial globe published in 1598 in Amsterdam by Plancius and Jodocus Hondius and was depicted in Johann Bayer's star atlas Uranometria of 1603. French explorer and astronomer Nicolas Louis de Lacaille gave its stars Bayer designations in 1756. The constellations Tucana, Grus, Phoenix and Pavo are collectively known as the "Southern Birds".

Triangulum Australe is a small constellation in the far Southern Celestial Hemisphere. Its name is Latin for "the southern triangle", which distinguishes it from Triangulum in the northern sky and is derived from the acute, almost equilateral pattern of its three brightest stars. It was first depicted on a celestial globe as Triangulus Antarcticus by Petrus Plancius in 1589, and later with more accuracy and its current name by Johann Bayer in his 1603 Uranometria. The French explorer and astronomer Nicolas Louis de Lacaille charted and gave the brighter stars their Bayer designations in 1756.

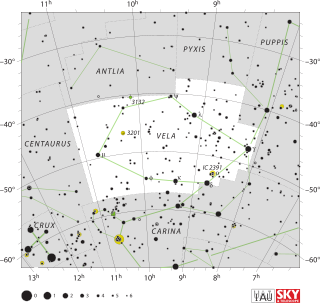

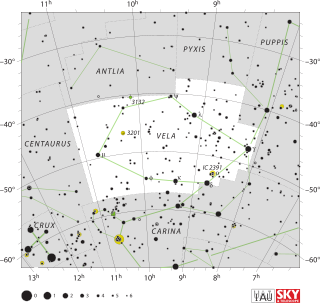

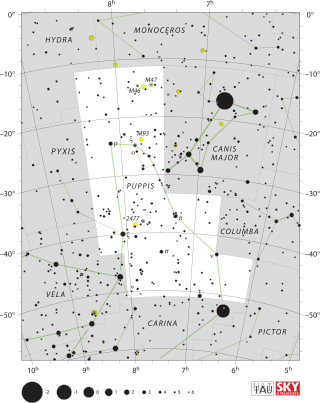

Vela is a constellation in the southern sky, which contains the Vela Supercluster. Its name is Latin for the sails of a ship, and it was originally part of a larger constellation, the ship Argo Navis, which was later divided into three parts, the others being Carina and Puppis. With an apparent magnitude of 1.8, its brightest star is the hot blue multiple star Gamma Velorum, one component of which is the closest and brightest Wolf-Rayet star in the sky. Delta and Kappa Velorum, together with Epsilon and Iota Carinae, form the asterism known as the False Cross. 1.95-magnitude Delta is actually a triple or quintuple star system.

In astronomy, a variable-star designation is a unique identifier given to variable stars. It extends on the Bayer designation format, with an identifying label preceding the Latin genitive of the name of the constellation in which the star lies. The identifying label can be one or two Latin letters or a V plus a number. Examples are R Coronae Borealis, YZ Ceti, V603 Aquilae.

Pavo is a constellation in the southern sky whose name is Latin for 'peacock'. Pavo first appeared on a 35-cm (14 in) diameter celestial globe published in 1598 in Amsterdam by Petrus Plancius and Jodocus Hondius and was depicted in Johann Bayer's star atlas Uranometria of 1603, and was likely conceived by Plancius from the observations of Pieter Dirkszoon Keyser and Frederick de Houtman. French explorer and astronomer Nicolas-Louis de Lacaille gave its stars Bayer designations in 1756. The constellations Pavo, Grus, Phoenix and Tucana are collectively known as the "Southern Birds".

In ancient times, only the Sun and Moon, a few stars, and the most easily visible planets had names. Over the last few hundred years, the number of identified astronomical objects has risen from hundreds to over a billion, and more are discovered every year. Astronomers need to be able to assign systematic designations to unambiguously identify all of these objects, and at the same time give names to the most interesting objects, and where relevant, features of those objects.

An asterism is an observed pattern or group of stars in the sky. Asterisms can be any identified pattern or group of stars, and therefore are a more general concept than the 88 formally defined constellations. Constellations are based on asterisms, but unlike asterisms, constellations outline and today completely divide the sky and all its celestial objects into regions around their central asterisms. For example, the asterism known as the Big Dipper or the Plough comprises the seven brightest stars in the constellation Ursa Major. Another asterism is the triangle, within the constellation of Capricornus.

Omicron Scorpii is a star in the zodiac constellation of Scorpius. With an apparent visual magnitude of +4.57, it is visible to the naked eye. Parallax measurements indicate a distance of roughly 900 light years. It is located in the proximity of the Rho Ophiuchi dark cloud.

Omicron Velorum is a star in the constellation Vela. It is the brightest member of the loose naked eye open cluster IC 2391, also known as the ο Velorum Cluster.

This table lists those stars or other objects which have Bayer designations, grouped by the constellation part of the designation.

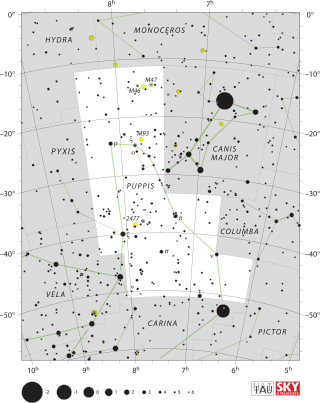

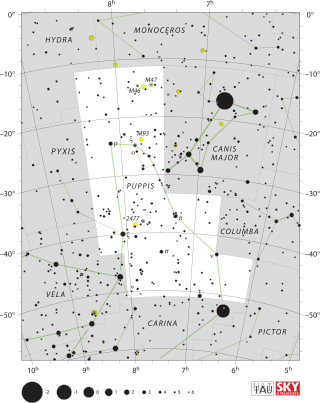

k Puppis is a Bayer designation given to an optical double star in the constellation Puppis, the two components being k1 Puppis and k2 Puppis.

Omicron Puppis (ο Puppis) is candidate binary star system in the southern constellation of Puppis. It is visible to the naked eye, having a combined apparent visual magnitude of +4.48. Based upon an annual parallax shift of 2.30 mas as seen from Earth, it is located roughly 1,400 light years from the Sun.