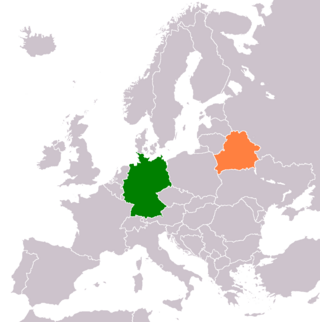

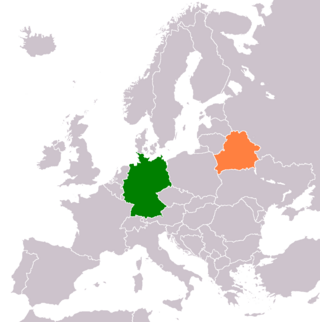

Belarus, officially the Republic of Belarus, is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by Russia to the east and northeast, Ukraine to the south, Poland to the west, and Lithuania and Latvia to the northwest. Covering an area of 207,600 square kilometres (80,200 sq mi) and with a population of 9.2 million, Belarus is the 13th-largest and the 20th-most populous country in Europe. The country has a hemiboreal climate and is administratively divided into six regions. Minsk is the capital and largest city; it is administered separately as a city with special status.

The lands of Belarus during the Middle Ages became part of Kievan Rus' and were split between different principalities, including Polotsk, Turov, Vitebsk, and others. Following the Mongol invasions of the 13th century, these lands were absorbed by the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, which later was merged into the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in the 16th century.

Minsk is the capital and the largest city of Belarus, located on the Svislach and the now subterranean Niamiha rivers. As the capital, Minsk has a special administrative status in Belarus and is the administrative centre of Minsk Region and Minsk District. As of 2024, it has a population of about two million, making Minsk the 11th-most populous city in Europe. Minsk is one of the administrative capitals of the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) and the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU).

The politics of Belarus takes place in a framework of a presidential republic with a bicameral parliament. The President of Belarus is the head of state. Executive power is nominally exercised by the government, at its top sits a ceremonial prime minister, appointed directly by the President. Legislative power is de jure vested in the bicameral parliament, the National Assembly, however the president may enact decrees that are executed the same way as laws, for undisputed time.

Alexander Grigoryevich Lukashenko is a Belarusian politician who has been the president of Belarus since the office's establishment in 1994. This makes him the longest-serving European president.

Pyotr Mironovich Masherov was a Soviet partisan, statesman, and one of the leaders of the Belarusian resistance during World War II who governed the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic as First Secretary of the Communist Party of Byelorussia from 1965 until his death in 1980. Under Masherov's rule, Belarus was transformed from an agrarian, undeveloped nation which had not yet recovered from the Second World War into an industrial powerhouse; Minsk, the capital and largest city of Belarus, became one of the fastest-growing cities on the planet. Masherov ruled until his sudden death in 1980, after his vehicle was hit by a potato truck.

The Belarusian resistance during World War II opposed Nazi Germany from 1941 until 1944. Belarus was one of the Soviet republics occupied during Operation Barbarossa. The term Belarusian partisans may refer to Soviet-formed irregular military groups fighting Germany, but has also been used to refer to the disparate independent groups who also fought as guerrillas at the time, including Jewish groups, Polish groups, and nationalist Belarusian forces opposed to Germany.

Mutual relations between the Republic of Belarus and the European Union (EU) were initially established after the European Economic Community recognised Belarusian independence in 1991.

Belarus and Russia share a land border and constitute the supranational Union State. Several treaties have been concluded between the two nations bilaterally. Russia is Belarus' largest and most important economic and political partner. Both are members of various international organizations, including the Commonwealth of Independent States, the Eurasian Economic Union, the Collective Security Treaty Organization, and the United Nations.

Belarus and Ukraine are both are full members of the Baku Initiative and Central European Initiative. In 2020, during the Belarusian protests against president Lukashenko, the relationship between Ukraine and Belarus began to deteriorate, after the Ukrainian government criticized Belarusian president Alexander Lukashenko. In the waning days of 2021, the relationship between both countries rapidly deteriorated, culminating in a full-scale invasion on 24 February 2022. Belarus has allowed the stationing of Russian troops and equipment in its territory and its use as a springboard for offensives into northern Ukraine but has denied the presence of Belarusian troops in Ukraine. Even though part of the Russian invasion was launched from Belarus, Ukraine did not break off diplomatic relations with Belarus, but remain frozen.

Eastern Belorussia is a historical region of Belarus traditionally inhabited by members of the Eastern Orthodox Church, in contrast to the largely-Catholic western Belorussia. Historically dominated politically by the peasantry, eastern Belorussia was a stronghold of the Belarusian Socialist Assembly after the February Revolution and later became the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic during the interwar period.

Nikolai Semyonovich Patolichev was a Soviet statesman who served as Minister of Foreign Trade of the USSR from 1958 to 1985. Prior to that, he was the First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Byelorussia from 1950 to 1956.

Mikhail Vasilyevich Zimyanin was a Belarusian Soviet partisan, politician, and diplomat who served as the editor-in-chief of the newspaper Pravda, the official publication of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, from 1965 to 1976. Afterwards, he was appointed to the party's secretariat. He retired on 28 January 1987 for "health reasons".

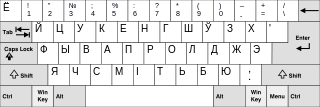

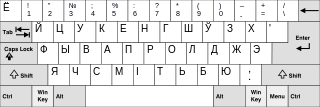

The official languages of Belarus are Belarusian and Russian.

The Belarusian opposition consists of groups and individuals in Belarus seeking to challenge, from 1988 to 1991, the authorities of Soviet Belarus, and since 1995, the leader of the country Alexander Lukashenko, whom supporters of the movement often consider to be a dictator. Supporters of the movement tend to call for a parliamentary democracy based on a Western model, with freedom of speech and political and religious pluralism.

Belarusian nationalism refers to the belief that Belarusians should constitute an independent nation. Belarusian nationalism began emerging in the mid-19th century, during the January Uprising against the Russian Empire. Belarus first declared independence in 1917 as the Belarusian Democratic Republic, but was subsequently invaded and annexed by the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic in 1918, becoming part of the Soviet Union. Belarusian nationalists both collaborated with and fought against Nazi Germany during World War II, and protested for the independence of Belarus during the late 1980s and early 1990s.

Independence Square is a square in Minsk, Belarus. It is one of the landmarks on Independence Avenue. The National Assembly of Belarus and Minsk City Hall are on this square. During the period of the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic it was called Lenin Square. It is currently one of the largest squares in Europe.

The 1991 Belarusian strikes, also referred to in Belarus as the April Strikes, were a series of nationwide strikes and rallies in the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic. Originally in opposition to price increases and a tax on goods from republics sold in another republic, the protests later turned into a broadly anti-Soviet movement, calling for the resignation of Soviet leadership, a reduction of the economic role of the Soviet government, and fresh elections to the Supreme Soviet of the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic.

Germany has an embassy in Minsk. Belarus has an embassy in Berlin, a consulate general in Munich, and two honorary consulates in Cottbus and Hamburg.

The Freedom March was a 1999 protest by the Belarusian opposition in the Belarusian capital of Minsk. The protest was caused as a result of fears of Belarus being annexed into Russia as part of the then-impending ratification of the Union State. Additional concerns of protesters were the enforced disappearances of opposition politicians Viktar Hanchar and Yury Zacharanka and, more broadly, the authoritarian rule of President Alexander Lukashenko. The protest, which ended in a violent confrontation between the city's police and protesters, resulted in the Belarusian government walking back plans for the Union State and the continued independence of Belarus from Russia.

![Prior to the mid-1950s, most of Belarus comprised small villages (modern example Siemierniki [be] pictured) Semerniki village Belarus 2016.jpg](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/50/Semerniki_village_Belarus_2016.jpg/220px-Semerniki_village_Belarus_2016.jpg)