Related Research Articles

Emilio Aguinaldo y Famy was a Filipino revolutionary, statesman, and military leader who was the youngest president of the Philippines (1899–1901) and became the first president of the Philippines and of an Asian constitutional republic. He led the Philippine forces first against Spain in the Philippine Revolution (1896–1898), then in the Spanish–American War (1898), and finally against the United States during the Philippine–American War (1899–1901). Though he was not recognized as president outside of the revolutionary Philippines, he is regarded in the Philippines as having been the country's first president during the period of the First Philippine Republic.

The Philippine–American War, known alternatively as the Philippine Insurrection, Filipino–American War, or Tagalog Insurgency, emerged following the conclusion of the Spanish–American War in December 1898 when the United States annexed the Philippine Islands under the Treaty of Paris. Philippine nationalists constituted the First Philippine Republic in January 1899, seven months after signing the Philippine Declaration of Independence. The United States did not recognize either event as legitimate, and tensions escalated until fighting commenced on February 4, 1899 in the Battle of Manila.

Elwell Stephen Otis was a United States Army general who served in the American Civil War, Indian Wars, the Philippines late in the Spanish–American War and during the Philippine–American War.

The Philippine Revolution was a war of independence waged by the revolutionary organization Katipunan against the Spanish Empire from 1896 to 1898. It was the culmination of the 333-year colonial rule of Spain in the archipelago. The Philippines was one of the last major colonies of the Spanish Empire, which had already suffered a massive decline in the 1820s. Cuba rebelled in 1895, and in 1898, the United States intervened and the Spanish soon capitulated. In June, Philippine revolutionaries declared independence. However, it was not recognized by Spain, which sold the islands to the United States in the Treaty of Paris.

The Battle of Manila, sometimes called the Mock Battle of Manila, was a land engagement which took place in Manila on August 13, 1898, at the end of the Spanish–American War, three months after the decisive victory by Commodore Dewey's Asiatic Squadron at the Battle of Manila Bay. The belligerents were Spanish forces led by Governor-General of the Philippines Fermín Jáudenes, and American forces led by United States Army Major General Wesley Merritt and United States Navy Commodore George Dewey. American forces were supported by units of the Philippine Revolutionary Army, led by Emilio Aguinaldo.

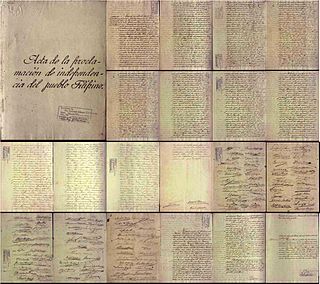

The Philippine Declaration of Independence was proclaimed by Filipino revolutionary forces general Emilio Aguinaldo on June 12, 1898, in Cavite el Viejo, Philippines. It asserted the sovereignty and independence of the Philippine islands from the 300 years of colonial rule from Spain.

The Battle of Manila, the first and largest battle of the Philippine–American War, was fought on February 4–5, 1899, between 19,000 American soldiers and 15,000 Filipino armed militiamen. Armed conflict broke out when American troops, under orders to turn away insurgents from their encampment, fired upon an encroaching group of Filipinos. Philippine President Emilio Aguinaldo attempted to broker a ceasefire, but American General Elwell Stephen Otis rejected it, and fighting escalated the next day. It ended in an American victory, although minor skirmishes continued for several days afterward.

The Philippine–American War, also known as the Philippine War of Independence or the Philippine Insurrection (1899–1902), was an armed conflict between Filipino revolutionaries and the government of the United States which arose from the struggle of the First Philippine Republic to gain independence following the Philippines being acquired by the United States from Spain. This article lists significant events from before, during, and after that war, with links to other articles containing more detail.

Don Sixto Castelo López was secretary of the Philippine mission sent to the United States in 1898 to negotiate US recognition of Philippine independence.

The Philippine Republic, now officially remembered as the First Philippine Republic and also referred to by historians as the Malolos Republic, was established in Malolos, Bulacan during the Philippine Revolution against the Spanish Empire (1896–1898) and the Spanish–American War between Spain and the United States (1898) through the promulgation of the Malolos Constitution on January 23, 1899, succeeding the Revolutionary Government of the Philippines. It was formally established with Emilio Aguinaldo as president. It was unrecognized outside of the Philippines but remained active until April 19, 1901. Following the American victory at the Battle of Manila Bay, Aguinaldo returned to the Philippines, issued the Philippine Declaration of Independence on June 12, 1898, and proclaimed successive revolutionary Philippine governments on June 18 and 23 of that year.

The history of the Philippines from 1898 to 1946 is known as the American colonial period, and began with the outbreak of the Spanish–American War in April 1898, when the Philippines was still a colony of the Spanish East Indies, and concluded when the United States formally recognized the independence of the Republic of the Philippines on July 4, 1946.

Don Felipe Agoncillo y Encarnación was the Filipino lawyer representative to the negotiations in Paris that led to the Treaty of Paris (1898), ending the Spanish–American War and achieving him the title of "outstanding first Filipino diplomat."

The Schurman Commission, also known as the First Philippine Commission, was established by United States President William McKinley on January 20, 1899, and tasked to study the situation in the Philippines and make recommendations on how the U.S. should proceed after the sovereignty of the Philippines was ceded to the U.S. by Spain on December 10, 1898, following the Treaty of Paris of 1898.

The Treaty of Manila of 1946, formally the Treaty of General Relations and Protocol, is a treaty of general relations signed on July 4, 1946, in Manila, the capital of the Philippines. It relinquished U.S. sovereignty over the Philippines and recognized the independence of the Republic of the Philippines. The treaty was signed by High Commissioner Paul V. McNutt as representative of the United States and President Manuel Roxas as representative of the Philippines.

The sovereignty of the Philippines refers to the status of the Philippines as an independent nation. This article covers sovereignty transitions relating to the Philippines, with particular emphasis on the passing of sovereignty from Spain to the United States in the Treaty of Paris (1898), signed on December 10, 1898, to end the Spanish–American War. US President William McKinley asserted the United States' sovereignty over the Philippines on December 21, 1898, through his Benevolent Assimilation Proclamation.

The Hong Kong Junta was an organization formed as a revolutionary government in exile by Filipino revolutionaries after the signing of the Pact of Biak-na-Bato on December 15, 1897. It was headed by Emilio Aguinaldo and included high-level figures in the Philippine revolution against Spanish rule who accompanied Aguinaldo into exile in British Hong Kong from the Philippines.

Fighting erupted between forces of the United States and those of the Philippine Republic on February 4, 1899, in what became known as the 1899 Battle of Manila. On June 2, 1899, the First Philippine Republic officially declared war against the United States. The war officially ended on July 2, 1902, with a victory for the United States. However, some Philippine groups—led by veterans of the Katipunan, a Philippine revolutionary society—continued to battle the American forces for several more years. Among those leaders was General Macario Sakay, a veteran Katipunan member who assumed the presidency of the proclaimed Tagalog Republic, formed in 1902 after the capture of President Emilio Aguinaldo. Other groups, including the Moro, Bicol and Pulahan peoples, continued hostilities in remote areas and islands, until their final defeat at the Battle of Bud Bagsak on June 15, 1913.

The following lists events that happened during 1899 in the Philippine Republic.

The Military Government of the Philippine Islands was a military government in the Philippines established by the United States on August 14, 1898, a day after the capture of Manila, with General Wesley Merritt acting as military governor. General Merrit established this military government by proclamation on August 14, 1898.

The Dictatorial Government of the Philippines was an insurgent government in the Spanish East Indies inaugurated during the Spanish–American War by Emilio Aguinaldo in a public address on May 24, 1898, on his return to the Philippines from exile in Hong Kong, and formally established on June 18. The government was officially a dictatorship with Aguinaldo formally holding the title of "Dictator". The government was succeeded by a revolutionary government which was established by Aguinaldo on June 23.

References

- ↑ "Filipinos Are Informed Just What the United States Intends To Do By A Presidential Proclamation". Los Angeles Herald. January 5, 1899 – via UCR Center for Bibliographic al Studies and Research.

- ↑ McFerson, Hazel M. (2002). Mixed Blessing: The Impact of the American Colonial Experience on Politics and Society in the Philippines. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 268. ISBN 978-0-313-30791-1.

- ↑ The text of the amended version published by General Otis is quoted in its entirety in José Roca de Togores y Saravia; Remigio Garcia; National Historical Institute (Philippines) (2003), Blockade and siege of Manila, National Historical Institute, pp. 148–150, ISBN 978-971-538-167-3 ; See also s:Letter from E.S. Otis to the inhabitants of the Philippine Islands, January 4, 1899.

- ↑ "McKinley's Benevolent Assimilation Proclamation". slideshare.net.

- ↑ Arnaldo Dumindin. "Dec. 21, 1898: Mckinley issues "Benevolent Assimilation" Proclamation". Philippine-American War, 1899-1902. MGen. Elwell S. Otis proclaims American protection over the Philippines. Typo error in this original press release submitted to Manila newspapers by the US army: the date "January 4, 1898" should have read "January 4, 1899.". Archived from the original on April 10, 2021.

- ↑ Miller, Stuart Creighton (1982), Benevolent Assimilation: The American Conquest of the Philippines, 1899-1903 (4th edition, reprint ed.), Yale University Press, p. 52, ISBN 978-0-300-03081-5