Related Research Articles

Chandragupta Maurya was the founder of the Maurya Empire, a geographically-extensive empire based in Magadha. He reigned from 320 BCE to 298 BCE. The Magadha kingdom expanded to become an empire that reached its peak under the reign of his grandson, Ashoka the Great, from 268 BCE to 231 BCE. The nature of the political formation that existed in Chandragupta's time is not certain. The Mauryan empire was a loose-knit one with large autonomous regions within its limits.

The Śvetāmbara is one of the two main branches of Jainism, the other being the Digambara. Śvetāmbara in Sanskrit means "white-clad", and refers to its ascetics' practice of wearing white clothes, which sets it apart from the Digambara or "sky-clad" Jains whose ascetic practitioners go nude. Śvetāmbaras do not believe that ascetics must practice nudity.

Varāhamihira, also called Varāha or Mihira, was an astrologer-astronomer who lived in or around Ujjain in present-day Madhya Pradesh, India.

Parshvanatha, or Pārśva and Pārasanātha, was the 23rd of 24 Tirthankaras of Jainism. He gained the title of Kalīkālkalpataru.

Utpala, also known as Bhaṭṭotpala was an astronomer from Kashmir region of present-day India, who lived in the 10th century. He wrote several Sanskrit-language texts on astrology and astronomy, the best-known being his commentaries on the works of the 6th-century astrologer-astronomer Varāhamihira.

Ācārya Bhadrabāhu was, according to both the Śvetāmbara and Digambara sects of Jainism, the last Shruta Kevalin in Jainism.

Bṛhat-saṃhitā is a 6th-century Sanskrit-language encyclopedia compiled by Varāhamihira in present-day Ujjain, India. Besides the author's area of expertise—astrology and astronomy—the work contains a wide variety of other topics.

The Bhaktāmara Stotra is a Jain religious hymn (stotra) written in Sanskrit. It was authored by Manatunga. The Digambaras believe it has 48 verses while Śvetāmbaras believe it consists of 44 verses.

Jainism is a religion founded in ancient India. Jains trace their history through twenty-four tirthankara and revere Rishabhanatha as the first tirthankara. The last two tirthankara, the 23rd tirthankara Parshvanatha and the 24th tirthankara Mahavira are considered historical figures. According to Jain texts, the 22nd tirthankara Neminatha lived about 5,000 years ago and was the cousin of Krishna.

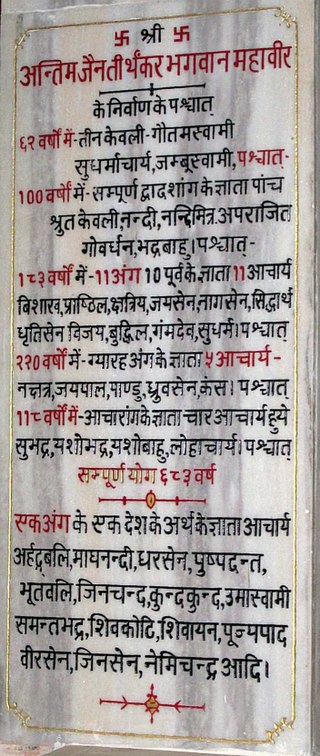

A Pattavali, Sthaviravali or Theravali, is a record of a spiritual lineage of heads of monastic orders. They are thus spiritual genealogies. It is generally presumed that two successive names are teacher and pupil. The term is applicable for all Indian religions, but is generally used for Jain monastic orders.

Sthulabhadra was a Jain monk who lived during the 3rd or 4th century BC. He was a disciple of Bhadrabahu and Sambhutavijaya. His father was Sakatala, a minister in Nanda kingdom before the arrival of Chandragupta Maurya. When his brother became the chief minister of the kingdom, Sthulabhadra became a Jain monk and suceeded Bhadrabahu in the Pattavali as per the writings of the Kalpa Sūtra. He is mentioned in the 12th-century Jain text Parisistaparvan by Hemachandra.

Jain literature refers to the literature of the Jain religion. It is a vast and ancient literary tradition, which was initially transmitted orally. The oldest surviving material is contained in the canonical Jain Agamas, which are written in Ardhamagadhi, a Prakrit language. Various commentaries were written on these canonical texts by later Jain monks. Later works were also written in other languages, like Sanskrit and Maharashtri Prakrit.

Digambara is one of the two major schools of Jainism, the other being Śvetāmbara (white-clad). The Sanskrit word Digambara means "sky-clad", referring to their traditional monastic practice of neither possessing nor wearing any clothes.

Acharya Manatunga was the author of the Jain prayer Bhaktamara Stotra. His name only appears in the last stanza of the said prayer. He is also credited with composing another Śvetāmbara hymn titled Namiun Stotra or Bhayahara Stotra, an adoration of Parshvanatha.

Jainism is an Indian religion which is traditionally believed to be propagated by twenty-four spiritual teachers known as tirthankara. Broadly, Jainism is divided into two major schools of thought, Digambara and Śvetāmbara. These are further divided into different sub-sects and traditions. While there are differences in practices, the core philosophy and main principles of each sect is the same.

Shrutakevalin a term used in Jainism for those ascetics who have complete knowledge of Jain Agamas. Shrutakevalin and Kevalin are equal from the perspective of knowledge, but Shrutajnana is Paroksha (indirect) whereas kevala jnana (omniscience) is pratyaksha (direct). Kevali can describe infinite part of the infinite knowledge that they possess. Shrutakevalins are learned of 14 Purvas.

Prabandha is a literary genre of medieval Indian Sanskrit literature. The prabandhas contain semi-historical anecdotes about the lives of famous persons. They were written primarily by Jain scholars of western India from 13th century onwards. The prabandhas feature colloquial Sanskrit with vernacular expressions, and contain elements of folklore.

Bhadrabahu was a Digambara monk from ancient India. He is called Bhadrabahu II or Bhadrabahu the Junior to distinguish him from the earlier Bhadrabahu.

Prabandha-Chintamani is an Indian Sanskrit-language collection of prabandhas. It was compiled in c. 1304 CE, in the Vaghela kingdom of present-day Gujarat, by Jain scholar Merutunga.

Samāsa Saṃhitā is a lost work on astrology by the 6th-century astrologer-astronomer Varāhamihira of present-day central India. An abridged version of Bṛhat Saṃhitā, it is known from excerpts in Utpala's commentary on the Bṛhat Saṃhitā.

References

- 1 2 Kailash Chand Jain (1991). Lord Mahāvīra and His Times. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 87. ISBN 978-81-208-0805-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 A.M. Shastri (1991). Varāhamihira and His Times. Kusumanjali. pp. 174–189. OCLC 28644897.