Related Research Articles

Psychosis is a condition of the mind that results in difficulties determining what is real and what is not real. Symptoms may include delusions and hallucinations, among other features. Additional symptoms are incoherent speech and behavior that is inappropriate for a given situation. There may also be sleep problems, social withdrawal, lack of motivation, and difficulties carrying out daily activities. Psychosis can have serious adverse outcomes.

A mental disorder is an impairment of the mind disrupting normal thinking, feeling, mood, behavior, or social interactions, and accompanied by significant distress or dysfunction. The causes of mental disorders are very complex and vary depending on the particular disorder and the individual. Although the causes of most mental disorders are not fully understood, researchers have identified a variety of biological, psychological, and environmental factors that can contribute to the development or progression of mental disorders. Most mental disorders result in a combination of several different factors rather than just a single factor.

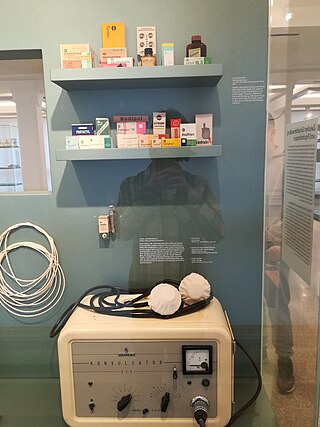

A psychiatric or psychotropic medication is a psychoactive drug taken to exert an effect on the chemical makeup of the brain and nervous system. Thus, these medications are used to treat mental illnesses. These medications are typically made of synthetic chemical compounds and are usually prescribed in psychiatric settings, potentially involuntarily during commitment. Since the mid-20th century, such medications have been leading treatments for a broad range of mental disorders and have decreased the need for long-term hospitalization, thereby lowering the cost of mental health care. The recidivism or rehospitalization of the mentally ill is at a high rate in many countries, and the reasons for the relapses are under research.

Abnormal psychology is the branch of psychology that studies unusual patterns of behavior, emotion, and thought, which could possibly be understood as a mental disorder. Although many behaviors could be considered as abnormal, this branch of psychology typically deals with behavior in a clinical context. There is a long history of attempts to understand and control behavior deemed to be aberrant or deviant, and there is often cultural variation in the approach taken. The field of abnormal psychology identifies multiple causes for different conditions, employing diverse theories from the general field of psychology and elsewhere, and much still hinges on what exactly is meant by "abnormal". There has traditionally been a divide between psychological and biological explanations, reflecting a philosophical dualism in regard to the mind-body problem. There have also been different approaches in trying to classify mental disorders. Abnormal includes three different categories; they are subnormal, supernormal and paranormal.

Schizoaffective disorder is a mental disorder characterized by abnormal thought processes and an unstable mood. This diagnosis requires symptoms of both schizophrenia and a mood disorder: either bipolar disorder or depression. The main criterion is the presence of psychotic symptoms for at least two weeks without any mood symptoms. Schizoaffective disorder can often be misdiagnosed when the correct diagnosis may be psychotic depression, bipolar I disorder, schizophreniform disorder, or schizophrenia. This is a problem as treatment and prognosis differ greatly for most of these diagnoses.

Anhedonia is a diverse array of deficits in hedonic function, including reduced motivation or ability to experience pleasure. While earlier definitions emphasized the inability to experience pleasure, anhedonia is currently used by researchers to refer to reduced motivation, reduced anticipatory pleasure (wanting), reduced consummatory pleasure (liking), and deficits in reinforcement learning. In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), anhedonia is a component of depressive disorders, substance-related disorders, psychotic disorders, and personality disorders, where it is defined by either a reduced ability to experience pleasure, or a diminished interest in engaging in previously pleasurable activities. While the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) does not explicitly mention anhedonia, the depressive symptom analogous to anhedonia as described in the DSM-5 is a loss of interest or pleasure.

Edwin Fuller Torrey, is an American psychiatrist and schizophrenia researcher. He is associate director of research at the Stanley Medical Research Institute (SMRI) and founder of the Treatment Advocacy Center (TAC), a nonprofit organization whose principal activity is promoting the passage and implementation of outpatient commitment laws and civil commitment laws and standards in individual states that allow people diagnosed with severe mental illness to be involuntarily hospitalized and treated throughout the United States.

Biological psychiatry or biopsychiatry is an approach to psychiatry that aims to understand mental disorder in terms of the biological function of the nervous system. It is interdisciplinary in its approach and draws on sciences such as neuroscience, psychopharmacology, biochemistry, genetics, epigenetics and physiology to investigate the biological bases of behavior and psychopathology. Biopsychiatry is the branch of medicine which deals with the study of the biological function of the nervous system in mental disorders.

Medical model is the term coined by psychiatrist R. D. Laing in his The Politics of the Family and Other Essays (1971), for the "set of procedures in which all doctors are trained". It includes complaint, history, physical examination, ancillary tests if needed, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis with and without treatment.

Disrupted in schizophrenia 1 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the DISC1 gene. In coordination with a wide array of interacting partners, DISC1 has been shown to participate in the regulation of cell proliferation, differentiation, migration, neuronal axon and dendrite outgrowth, mitochondrial transport, fission and/or fusion, and cell-to-cell adhesion. Several studies have shown that unregulated expression or altered protein structure of DISC1 may predispose individuals to the development of schizophrenia, clinical depression, bipolar disorder, and other psychiatric conditions. The cellular functions that are disrupted by permutations in DISC1, which lead to the development of these disorders, have yet to be clearly defined and are the subject of current ongoing research. Although, recent genetic studies of large schizophrenia cohorts have failed to implicate DISC1 as a risk gene at the gene level, the DISC1 interactome gene set was associated with schizophrenia, showing evidence from genome-wide association studies of the role of DISC1 and interacting partners in schizophrenia susceptibility.

Psychiatry is the medical specialty devoted to the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of deleterious mental conditions. These include various matters related to mood, behaviour, cognition, perceptions, and emotions.

Biological psychopathology is the study of the biological etiology of mental illnesses with a particular emphasis on the genetic and neurophysiological basis of clinical psychology. Biological psychopathology attempts to explain psychiatric disorders using multiple levels of analysis from the genome to brain functioning to behavior. Although closely related to clinical psychology, it is fundamentally an interdisciplinary approach that attempts to synthesize methods across fields such as neuroscience, psychopharmacology, biochemistry, genetics, and physiology. It is known by several alternative names, including "clinical neuroscience" and "experimental psychopathology." Due to the focus on biological processes of the central and peripheral nervous systems, biological psychopathology has been important in developing new biologically-based treatments for mental disorders.

The causes of schizophrenia that underlie the development of schizophrenia, a psychiatric disorder, are complex and not clearly understood. A number of hypotheses including the dopamine hypothesis, and the glutamate hypothesis have been put forward in an attempt to explain the link between altered brain function and the symptoms and development of schizophrenia.

The diagnosis of schizophrenia, a psychotic disorder, is based on criteria in either the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, or the World Health Organization's International Classification of Diseases (ICD). Clinical assessment of schizophrenia is carried out by a mental health professional based on observed behavior, reported experiences, and reports of others familiar with the person. Diagnosis is usually made by a psychiatrist. Associated symptoms occur along a continuum in the population and must reach a certain severity and level of impairment before a diagnosis is made. Schizophrenia has a prevalence rate of 0.3-0.7% in the United States

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to psychiatry:

Schizophrenia is a primary psychotic disorder, whereas, bipolar disorder is a primary mood disorder which can also involve psychosis. Both schizophrenia and bipolar disorder are characterized as critical psychiatric disorders in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders fifth edition (DSM-5). However, because of some similar symptoms, differentiating between the two can sometimes be difficult; indeed, there is an intermediate diagnosis termed schizoaffective disorder.

Joanna Moncrieff is a British psychiatrist and academic. She is Professor of Critical and Social Psychiatry at University College London and a leading figure in the Critical Psychiatry Network. She is a prominent critic of the modern 'psychopharmacological' model of mental disorder and drug treatment, and the role of the pharmaceutical industry. She has written papers, books and blogs on the use and over-use of drug treatment for mental health problems, the mechanism of action of psychiatric drugs, their subjective and psychoactive effects, the history of drug treatment, and the evidence for its benefits and harms. She also writes on the history and politics of psychiatry more generally. Her best known books are The Myth of the Chemical Cure and The Bitterest Pills.

Psychiatry is, and has historically been, viewed as controversial by those under its care, as well as sociologists and psychiatrists themselves. There are a variety of reasons cited for this controversy, including the subjectivity of diagnosis, the use of diagnosis and treatment for social and political control including detaining citizens and treating them without consent, the side effects of treatments such as electroconvulsive therapy, antipsychotics and historical procedures like the lobotomy and other forms of psychosurgery or insulin shock therapy, and the history of racism within the profession in the United States.

Lori Altshuler was a professor at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences and held the Julia S. Gouw Endowed Chair for Mood Disorders. Altshuler was the Director of the UCLA Mood Disorders Research Program and the UCLA Women's Life Center, each being part of the Neuropsychiatric Hospital at UCLA.

Epigenetics of bipolar disorder is the effect that epigenetics has on triggering and maintaining bipolar disorder.

References

- ↑ Pam, Alvin (1995). "Biological psychiatry: science or pseudoscience?". In Colin Ross and Alvin Pam (ed.). Pseudoscience in Biological Psychiatry: Blaming the Body. NY: Wiley & Sons. pp. 7–84. ISBN 978-0-471-00776-0.

- ↑ APA statement on Diagnosis and Treatment of Mental Disorders, American Psychiatric Association, September 26, 2003

- ↑ Most psychiatric disorders share a small number of genetic risk factors, VCU study shows, Virginia Commonwealth University

- ↑ Pickard BS, Malloy MP, Clark L, Lehellard S, Ewald HL, Mors O, Porteous DJ, Blackwood DH, Muir WJ (March 2005). "Candidate psychiatric illness genes identified in patients with pericentric inversions of chromosome 18". Psychiatric Genetics. 15 (1): 37–44. doi:10.1097/00041444-200503000-00007. PMID 15722956. S2CID 46458951.

- ↑ Macgregor S, Visscher PM, Knott SA, Thomson P, Porteous DJ, Millar JK, Devon RS, Blackwood D, Muir WJ (December 2004). "A genome scan and follow-up study identify a bipolar disorder susceptibility locus on chromosome 1q42". Molecular Psychiatry. 9 (12): 1083–90. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001544 . PMID 15249933.

- ↑ van Belzen MJ, Heutink P (2006). "Genetic analysis of psychiatric disorders in humans". Genes, Brain and Behavior. 5 (Suppl 2): 25–33. doi:10.1111/j.1601-183X.2006.00223.x. PMID 16681798. S2CID 22726139.

- ↑ Meyer-Lindenberg A, Weinberger DR (October 2006). "Intermediate phenotypes and genetic mechanisms of psychiatric disorders". Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. 7 (10): 818–27. doi:10.1038/nrn1993. PMID 16988657. S2CID 10966780.

- ↑ Millar JK, Pickard BS, Mackie S, James R, Christie S, Buchanan SR, Malloy MP, Chubb JE, Huston E, Baillie GS, Thomson PA, Hill EV, Brandon NJ, Rain JC, Camargo LM, Whiting PJ, Houslay MD, Blackwood DH, Muir WJ, Porteous DJ (November 2005). "DISC1 and PDE4B are interacting genetic factors in schizophrenia that regulate cAMP signaling". Science. 310 (5751): 1187–91. Bibcode:2005Sci...310.1187M. doi:10.1126/science.1112915. PMID 16293762. S2CID 3060031.

- ↑ Kates WR (April 2007). "Inroads to mechanisms of disease in child psychiatric disorders". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 164 (4): 547–51. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.164.4.547. PMID 17403964.

- ↑ Van Gestel S, Van Broeckhoven C (October 2003). "Genetics of personality: are we making progress?". Molecular Psychiatry. 8 (10): 840–52. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001367 . PMID 14515135.

- ↑ Lidz T, Blatt S (April 1983). "Critique of the Danish-American studies of the biological and adoptive relatives of adoptees who became schizophrenic". The American Journal of Psychiatry. 140 (4): 426–34. doi:10.1176/ajp.140.4.426. PMID 6837778.

- ↑ Joseph, Jay (2003). The Gene Illusion: Genetic Research in Psychiatry and Psychology Under the Microscope. New York, NY: Algora. ISBN 978-0-87586-344-3.[ page needed ]

- ↑ Joseph, Jay (2006). The Missing Gene: Psychiatry, Heredity, and the Fruitless Search for Genes. NY: Algora Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87586-410-5.[ page needed ]

- ↑ "Jay Joseph The Missing Gene". Archived from the original on 2009-04-17. Retrieved 2006-06-16.

- ↑ McEwen BS, Chattarji S, Diamond DM, Jay TM, Reagan LP, Svenningsson P, Fuchs E (March 2010). "The neurobiological properties of tianeptine (Stablon): from monoamine hypothesis to glutamatergic modulation". Molecular Psychiatry. 15 (3): 237–49. doi:10.1038/mp.2009.80. PMC 2902200 . PMID 19704408.

- ↑ McLaren, Niall (2007). Humanizing Madness. Ann Arbor, MI: Loving Healing Press. pp. 3–21. ISBN 978-1-932690-39-2.

- ↑ McLaren, Niall (2009). Humanizing Psychiatry. Ann Arbor, MI: Loving Healing Press. pp. 17–18. ISBN 978-1-61599-011-5.

- 1 2 Sharfstein SS (August 2005). "Big Pharma and American Psychiatry: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly". Psychiatric News. 40 (16). American Psychiatric Association: 3. Archived from the original on 19 November 2007.

- ↑ Dana J, Loewenstein G (July 2003). "A social science perspective on gifts to physicians from industry". JAMA. 290 (2): 252–5. doi:10.1001/jama.290.2.252. PMID 12851281.

- ↑ "Code on Interactions With Health Care Professionals". PhRMA. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- ↑ Zipkin DA, Steinman MA (August 2005). "Interactions between pharmaceutical representatives and doctors in training. A thematic review". Journal of General Internal Medicine. 20 (8): 777–86. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0134.x. PMC 1490177 . PMID 16050893.

- ↑ Huskamp HA, Donohue JM, Koss C, Berndt ER, Frank RG (2008). "Generic entry, reformulations and promotion of SSRIs in the US". PharmacoEconomics. 26 (7): 603–16. doi:10.2165/00019053-200826070-00007. PMC 2719790 . PMID 18563951.