Harappa is an archaeological site in Pakistan, about 25 km (16 mi) north of Sahiwal. The Bronze Age Harappan civilisation, now more often called the Indus Valley Civilisation, is named after the site, which takes its name from a modern village near the former course of the Ravi River, which now runs 8 km (5.0 mi) to the north. The core of the Harappan civilisation extended over a large area, from Gujarat in the south, across Sindh and Rajasthan and extending into Punjab and Haryana. Numerous sites have been found outside the core area, including some as far east as Uttar Pradesh and as far west as Sutkagen-dor on the Makran coast of Balochistan, not far from Iran.

Great Zimbabwe is a medieval city in the south-eastern hills of the modern country of Zimbabwe, near Lake Mutirikwe and the town of Masvingo. It is thought to have been the capital of a kingdom during the Late Iron Age. Construction on the city began in the 11th century and continued until it was abandoned in the 15th century. The edifices were erected by ancestors of the Shona people, currently located in Zimbabwe and nearby countries. The stone city spans an area of 7.22 square kilometres (2.79 sq mi) and could have housed up to 18,000 people at its peak, giving it a population density of approximately 2,500 inhabitants per square kilometre (6,500/sq mi). It is recognised as a World Heritage Site by UNESCO.

The Drakensberg is the eastern portion of the Great Escarpment, which encloses the central Southern African plateau. The Great Escarpment reaches its greatest elevation – 2,000 to 3,482 metres within the border region of South Africa and Lesotho.

Mpumalanga is a province of South Africa. The name means "East", or literally "The Place Where the Sun Rises" in the Nguni languages. Mpumalanga lies in eastern South Africa, bordering Eswatini and Mozambique. It shares borders with the South African provinces of Limpopo to the north, Gauteng to the west, the Free State to the southwest, and KwaZulu-Natal to the south. The capital is Mbombela.

In agriculture, a terrace is a piece of sloped plane that has been cut into a series of successively receding flat surfaces or platforms, which resemble steps, for the purposes of more effective farming. This type of landscaping is therefore called terracing. Graduated terrace steps are commonly used to farm on hilly or mountainous terrain. Terraced fields decrease both erosion and surface runoff, and may be used to support growing crops that require irrigation, such as rice. The Rice Terraces of the Philippine Cordilleras have been designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site because of the significance of this technique.

Khami is a ruined city located 22 kilometres (14 mi) west of Bulawayo, in Zimbabwe. It was once the capital of the Kingdom of Butua of the Torwa dynasty. It is now a national monument and became a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1986.

Ollantaytambo is a town and an Inca archaeological site in southern Peru some 72 km (45 mi) by road northwest of the city of Cusco. It is located at an altitude of 2,792 m (9,160 ft) above sea level in the district of Ollantaytambo, province of Urubamba, Cusco region. During the Inca Empire, Ollantaytambo was the royal estate of Emperor Pachacuti, who conquered the region, and built the town and a ceremonial center. At the time of the Spanish conquest of Peru, it served as a stronghold for Manco Inca Yupanqui, leader of the Inca resistance. Located in the Sacred Valley of the Incas, it is now an important tourist attraction on account of its Inca ruins and its location en route to one of the most common starting points for the four-day, three-night hike known as the Inca Trail.

Machadodorp, also known by its official name eNtokozweni, is a small town situated on the N4 road, near the edge of the escarpment in the Mpumalanga province, South Africa. The Elands River runs through the town. There is a natural radioactive spring here that is reputed to have powerful healing qualities.

White River is a small holiday and farming town situated just north of Mbombela in Mpumalanga, South Africa. The farms in the region produce tropical fruits, macadamia nuts, vegetables, flowers and timber. As of 2011, White River had a population of 16,639.

The Rhine Gorge is a popular name for the Upper Middle Rhine Valley, a 65 km section of the Rhine between Koblenz and Rüdesheim in the states of Rhineland-Palatinate and Hesse in Germany. It was added to the UNESCO list of World Heritage Sites in June 2002 because of its beauty as a cultural landscape, its importance as a route of transport across Europe, and the unique adaptations of the buildings and terraces to the steep slopes of the gorge.

The Kingdom of Mapungubwe was a medieval state in South Africa located at the confluence of the Shashe and Limpopo rivers, south of Great Zimbabwe. The name is derived from either TjiKalanga and Tshivenda. The name might mean "Hill of Jackals" or "stone monuments". The kingdom was the first stage in a development that would culminate in the creation of the Kingdom of Zimbabwe in the 13th century, and with gold trading links to Rhapta and Kilwa Kisiwani on the African east coast. The Kingdom of Mapungubwe lasted about 140 years, and at its height the capital's population was about 5000 people.

Dholavira is an archaeological site at Khadirbet in Bhachau Taluka of Kutch District, in the state of Gujarat in western India, which has taken its name from a modern-day village 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) south of it. This village is 165 km (103 mi) from Radhanpur. Also known locally as Kotada timba, the site contains ruins of a city of the ancient Indus Valley civilization. Earthquakes have repeatedly affected Dholavira, including a particularly severe one around 2600 BCE.

Sukur or Sukur Cultural Landscape is a UNESCO World Heritage Site located on a hill above the village of Sukur in the Adamawa State of Nigeria. It is situated in the Mandara Mountains, close to the border with Cameroon. Its UNESCO inscription is based on the cultural heritage, material culture, and the naturally-terraced fields. Sukur is Africa's first cultural landscape to receive World Heritage List inscription.

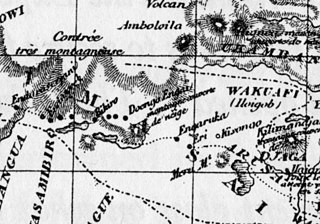

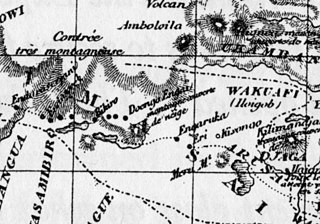

Engaruka is an abandoned system of ruins located in northwest Monduli District in central Arusha Region. The site is in geographical range of the Great Rift Valley of northern Tanzania. Situated in the Monduli District, it is famed for its irrigation and cultivation structures. It is considered one of the most important Iron Age archaeological sites in Tanzania. The site is located in the ward of Engaruka. The site is registered as one of the National Historic Sites of Tanzania.

Ziwa is an archaeological site in Nyanga District, Zimbabwe, containing the remains of a vast late Iron Age agricultural settlement dated to the 15th century. It is one of many sites that compose the Nyanga Iron Age ruins. Ziwa was declared a National Monument in 1946 and is currently under consideration for World Heritage listing. The site contains a large variety of stonework structures including stone terraces running along contours of hills and steep landscapes. Archaeological investigations have also uncovered important aspects of pottery and rock art.

The Dzata Ruins, an archaeological site in Dzanani in the Makhado municipality, Vhembe district, in the north of South Africa, is one of the national monuments in South Africa.

Thimlich Ohinga is a complex of stone-built ruins in Migori county, Nyanza Kenya, in East Africa. It is the largest one of 138 sites containing 521 stone structures that were built around the Lake Victoria region in Kenya. These sites are highly clustered. The main enclosure of Thimlich Ohinga has walls that are 1–3 m (3.3–9.8 ft) in thickness, and 1–4.2 m (3.3–13.8 ft) in height. The structures were built from undressed blocks, rocks, and stones set in place without mortar. The densely packed stones interlock. The site is believed to date to the 15th century or earlier.

The architecture of Zimbabwe is composed of three architectural types: the Hill Complex, the Valley Complex, and the Great Enclosure. Both traditional and colonial architectures have influenced the history and culture of the country. However, post-1954 buildings are mainly inspired by pre-colonial, traditional architecture, especially Great Zimbabwe–inspired structures such as the Kingdom Hotel, Harare international airport, and the National Heroes' Acre.

Bokoni was a pre-colonial, agro-pastoral society found in northwestern and southern parts of present-day Mpumalanga province, South Africa. Iconic to this area are stone-walled sites, found in a variety of shapes and forms. Bokoni sites also exhibit specialized farming and long-distance trading with other groups in surrounding regions. Bokoni saw occupation in varying forms between approximately 1500 and 1820 A.D.

Kweneng’ ruins are the remains of a pre-colonial Tswana capital occupied from the 15th to the 19th century AD in South Africa. The site is located 30km south of the modern-day city of Johannesburg. Settlement at the site likely began around the 1400s and saw its peak in the 15th century. The Kweneng' ruins are similar to those built by other early civilizations found in the southern Africa region during this period, including the Luba–Lunda kingdom, Kingdom of Mutapa, Bokoni, and many others, as these groups share ancestry. Kweneng' was the largest of several sizable settlements inhabited by Tswana speakers prior to European arrival. Several circular stone walled family compounds are spread out over an area 10km long and 2km wide. It is likely that Kweneng' was abandoned in the 1820s during the period of colonial expansion-related civil wars known as the Mfecane or Difaqane, leading to the dispersal of its inhabitants.