In botany, a fruit is the seed-bearing structure in flowering plants that is formed from the ovary after flowering.

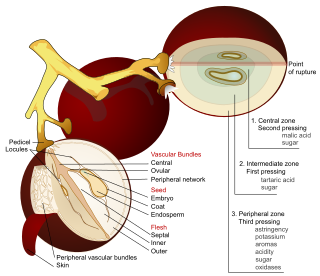

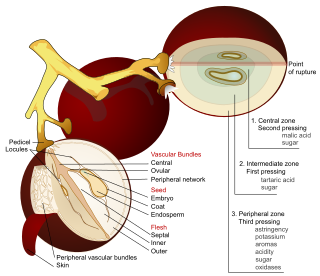

The persimmon is the edible fruit of a number of species of trees in the genus Diospyros. The most widely cultivated of these is the kaki persimmon, Diospyros kaki – Diospyros is in the family Ebenaceae, and a number of non-persimmon species of the genus are grown for ebony timber. In 2022, China produced 77% of the world total of persimmons.

Sauvignon blanc is a green-skinned grape variety that originates from the city of Bordeaux in France. The grape most likely gets its name from the French words sauvage ("wild") and blanc ("white") due to its early origins as an indigenous grape in South West France. It is possibly a descendant of Savagnin. Sauvignon blanc is planted in many of the world's wine regions, producing a crisp, dry, and refreshing white varietal wine. The grape is also a component of the famous dessert wines from Sauternes and Barsac. Sauvignon blanc is widely cultivated in France, Chile, Romania, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Bulgaria, the states of Oregon, Washington, and California in the US. Some New World Sauvignon blancs, particularly from California, may also be called "Fumé Blanc", a marketing term coined by Robert Mondavi in reference to Pouilly-Fumé.

Mangosteen, also known as the purple mangosteen, is a tropical evergreen tree with edible fruit native to Island Southeast Asia, from the Malay Peninsula to Borneo. It has been cultivated extensively in tropical Asia since ancient times. It is grown mainly in Southeast Asia, southwest India and other tropical areas such as Colombia, Puerto Rico and Florida, where the tree has been introduced. The tree grows from 6 to 25 m tall.

Ripening is a process in fruits that causes them to become more palatable. In general, fruit becomes sweeter, less green, and softer as it ripens. Even though the acidity of fruit increases as it ripens, the higher acidity level does not make the fruit seem tarter. This effect is attributed to the Brix-Acid Ratio. Climacteric fruits ripen after harvesting and so some fruits for market are picked green.

The loquat is a large evergreen shrub or tree grown commercially for its orange fruit. It is also cultivated as an ornamental plant.

The cherimoya, also spelled chirimoya and called chirimuya by the Inca people, is a species of edible fruit-bearing plant in the genus Annona, from the family Annonaceae, which includes the closely related sweetsop and soursop. The plant has long been believed to be native to Ecuador and Peru, with cultivation practised in the Andes and Central America, although a recent hypothesis postulates Central America as the origin instead, because many of the plant's wild relatives occur in this area.

Artocarpus integer, commonly known as chempedak or cempedak, is a species of tree in the family Moraceae, in the same genus as breadfruit and jackfruit. It is native to Southeast Asia. Cempedak is an important crop in Malaysia and is also popularly cultivated in southern Thailand and parts of Indonesia, and has the potential to be utilized in other areas. It is currently limited in range to Southeast Asia, with some trees in Australia and Hawaii.

Mespilus germanica, known as the medlar or common medlar, is a large shrub or small tree in the rose family Rosaceae. The fruit of this tree, also called medlar, has been cultivated since Roman times, is usually available in winter and eaten when bletted. It may be eaten raw and in a range of cooked dishes.

Diospyros virginiana is a persimmon species commonly called the American persimmon, common persimmon, eastern persimmon, simmon, possumwood, possum apples, or sugar plum. It ranges from southern Connecticut to Florida, and west to Texas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, Kansas, and Iowa. The tree grows in the wild but has been cultivated for its fruit and wood since prehistoric times by Native Americans.

Mespilus, commonly called medlar, is a monotypic genus of flowering plants in the family Rosaceae containing the single species Mespilus germanica of southwest Asia. It is also found in some countries in the Balkans, especially in Albanian and Bulgarian regions, and in western parts of Caucasian Georgia. A second proposed species, Mespilus canescens, discovered in North America in 1990, proved to be a hybrid between M. germanica and one or more species of hawthorn, and is properly known as × Crataemespilus canescens.

Mespilus canescens, commonly known as Stern's medlar, is a large shrub or small tree, recently discovered in Prairie County, Arkansas, United States, and formally named in 1990. It is a critically endangered endemic species, with only 25 plants known, all in one small wood, now protected as the Konecny Grove Natural Area.

In food processing, fermentation is the conversion of carbohydrates to alcohol or organic acids using microorganisms—yeasts or bacteria—without an oxidizing agent being used in the reaction. Fermentation usually implies that the action of microorganisms is desired. The science of fermentation is known as zymology or zymurgy.

Diospyros kaki, the Oriental persimmon, Chinese persimmon, Japanese persimmon or kaki persimmon, is the most widely cultivated species of the genus Diospyros. Although its first botanical description was not published until 1780, D. kaki cultivation in China dates back more than 2000 years.

Amelanchier × lamarckii, also called juneberry, serviceberry or shadbush, is a large deciduous flowering shrub or small tree in the family Rosaceae.

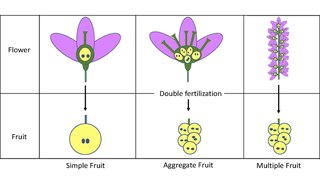

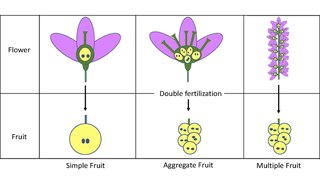

Fruits are the mature ovary or ovaries of one or more flowers. They are found in three main anatomical categories: aggregate fruits, multiple fruits, and simple fruits.

The acids in wine are an important component in both winemaking and the finished product of wine. They are present in both grapes and wine, having direct influences on the color, balance and taste of the wine as well as the growth and vitality of yeast during fermentation and protecting the wine from bacteria. The measure of the amount of acidity in wine is known as the “titratable acidity” or “total acidity”, which refers to the test that yields the total of all acids present, while strength of acidity is measured according to pH, with most wines having a pH between 2.9 and 3.9. Generally, the lower the pH, the higher the acidity in the wine. There is no direct connection between total acidity and pH. In wine tasting, the term “acidity” refers to the fresh, tart and sour attributes of the wine which are evaluated in relation to how well the acidity balances out the sweetness and bitter components of the wine such as tannins. Three primary acids are found in wine grapes: tartaric, malic, and citric acids. During the course of winemaking and in the finished wines, acetic, butyric, lactic, and succinic acids can play significant roles. Most of the acids involved with wine are fixed acids with the notable exception of acetic acid, mostly found in vinegar, which is volatile and can contribute to the wine fault known as volatile acidity. Sometimes, additional acids, such as ascorbic, sorbic and sulfurous acids, are used in winemaking.

Generally, fleshy fruits can be divided into two groups based on the presence or absence of a respiratory increase at the onset of ripening. This respiratory increase—which is preceded, or accompanied, by a rise in ethylene—is called a climacteric, and there are marked differences in the development of climacteric and non-climacteric fruits. Climacteric fruit can be either monocots or dicots and the ripening of these fruits can still be achieved even if the fruit has been harvested at the end of their growth period. Non-climacteric fruits ripen without ethylene and respiration bursts, the ripening process is slower, and for the most part they will not be able to ripen if the fruit is not attached to the parent plant. Examples of climacteric fruits include apples, bananas, melons, apricots, tomatoes, as well as most stone fruits. Non-climacteric fruits on the other hand include citrus fruits, grapes, and strawberries Essentially, a key difference between climacteric and non-climacteric fruits is that climacteric fruits continue to ripen following their harvest, whereas non-climacteric fruits do not. The accumulation of starch over the early stages of climacteric fruit development may be a key issue, as starch can be converted to sugars after harvest.

Simple fruits are the result of the ripening-to-fruit of a simple or compound ovary in a single flower with a single pistil. In contrast, a single flower with numerous pistils typically produces an aggregate fruit; and the merging of several flowers, or a 'multiple' of flowers, results in a 'multiple' fruit. A simple fruit is further classified as either dry or fleshy.

In viticulture, ripeness is the completion of the ripening process of wine grapes on the vine which signals the beginning of harvest. What exactly constitutes ripeness will vary depending on what style of wine is being produced and what the winemaker and viticulturist personally believe constitutes ripeness. Once the grapes are harvested, the physical and chemical components of the grape which will influence a wine's quality are essentially set so determining the optimal moment of ripeness for harvest may be considered the most crucial decision in winemaking.