Related Research Articles

In chemistry, a cyanide is a chemical compound that contains a C≡N functional group. This group, known as the cyano group, consists of a carbon atom triple-bonded to a nitrogen atom.

Hydrogen cyanide, sometimes called prussic acid, is a chemical compound with the formula HCN and structure H−C≡N. It is a colorless, extremely poisonous, and flammable liquid that boils slightly above room temperature, at 25.6 °C (78.1 °F). HCN is produced on an industrial scale and is a highly valued precursor to many chemical compounds ranging from polymers to pharmaceuticals. Large-scale applications are for the production of potassium cyanide and adiponitrile, used in mining and plastics, respectively. It is more toxic than solid cyanide compounds due to its volatile nature.

Potassium ferrocyanide is the inorganic compound with formula K4[Fe(CN)6]·3H2O. It is the potassium salt of the coordination complex [Fe(CN)6]4−. This salt forms lemon-yellow monoclinic crystals.

Prussian blue is a dark blue pigment produced by oxidation of ferrous ferrocyanide salts. It has the chemical formula FeIII

4[FeII

(CN)

6]

3. Turnbull's blue is chemically identical, but is made from different reagents, and its slightly different color stems from different impurities and particle sizes.

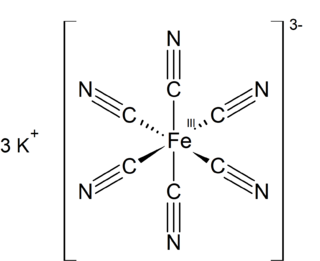

Potassium ferricyanide is the chemical compound with the formula K3[Fe(CN)6]. This bright red salt contains the octahedrally coordinated [Fe(CN)6]3− ion. It is soluble in water and its solution shows some green-yellow fluorescence. It was discovered in 1822 by Leopold Gmelin.

Syngas, or synthesis gas, is a mixture of hydrogen and carbon monoxide, in various ratios. The gas often contains some carbon dioxide and methane. It is principally used for producing ammonia or methanol. Syngas is combustible and can be used as a fuel. Historically, it has been used as a replacement for gasoline, when gasoline supply has been limited; for example, wood gas was used to power cars in Europe during WWII.

Potassium hydroxide is an inorganic compound with the formula KOH, and is commonly called caustic potash.

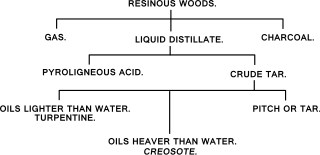

The pyrolysis process is the thermal decomposition of materials at elevated temperatures, often in an inert atmosphere. It involves a change of chemical composition. The word is coined from the Greek-derived elements pyro "fire", "heat", "fever" and lysis "separating".

Coal gas is a flammable gaseous fuel made from coal and supplied to the user via a piped distribution system. It is produced when coal is heated strongly in the absence of air. Town gas is a more general term referring to manufactured gaseous fuels produced for sale to consumers and municipalities.

Gold cyanidation is a hydrometallurgical technique for extracting gold from low-grade ore by converting the gold to a water-soluble coordination complex. It is the most commonly used leaching process for gold extraction. Cyanidation is also widely used in the extraction of silver, usually after froth flotation.

Environmental remediation deals with the removal of pollution or contaminants from environmental media such as soil, groundwater, sediment, or surface water. Remedial action is generally subject to an array of regulatory requirements, and may also be based on assessments of human health and ecological risks where no legislative standards exist, or where standards are advisory.

Dry distillation is the heating of solid materials to produce gaseous products. The method may involve pyrolysis or thermolysis, or it may not.

In industrial chemistry, coal gasification is the process of producing syngas—a mixture consisting primarily of carbon monoxide (CO), hydrogen, carbon dioxide, methane, and water vapour —from coal and water, air and/or oxygen.

Industrial wastewater treatment describes the processes used for treating wastewater that is produced by industries as an undesirable by-product. After treatment, the treated industrial wastewater may be reused or released to a sanitary sewer or to a surface water in the environment. Some industrial facilities generate wastewater that can be treated in sewage treatment plants. Most industrial processes, such as petroleum refineries, chemical and petrochemical plants have their own specialized facilities to treat their wastewaters so that the pollutant concentrations in the treated wastewater comply with the regulations regarding disposal of wastewaters into sewers or into rivers, lakes or oceans. This applies to industries that generate wastewater with high concentrations of organic matter, toxic pollutants or nutrients such as ammonia. Some industries install a pre-treatment system to remove some pollutants, and then discharge the partially treated wastewater to the municipal sewer system.

Petroleum coke, abbreviated coke or petcoke, is a final carbon-rich solid material that derives from oil refining, and is one type of the group of fuels referred to as cokes. Petcoke is the coke that, in particular, derives from a final cracking process—a thermo-based chemical engineering process that splits long chain hydrocarbons of petroleum into shorter chains—that takes place in units termed coker units. Stated succinctly, coke is the "carbonization product of high-boiling hydrocarbon fractions obtained in petroleum processing ". Petcoke is also produced in the production of synthetic crude oil (syncrude) from bitumen extracted from Canada’s oil sands and from Venezuela's Orinoco oil sands.

A gasworks or gas house is an industrial plant for the production of flammable gas. Many of these have been made redundant in the developed world by the use of natural gas, though they are still used for storage space.

Ferrocyanide is the name of the anion [Fe(CN)6]4−. Salts of this coordination complex give yellow solutions. It is usually available as the salt potassium ferrocyanide, which has the formula K4Fe(CN)6. [Fe(CN)6]4− is a diamagnetic species, featuring low-spin iron(II) center in an octahedral ligand environment. Although many salts of cyanide are highly toxic, ferro- and ferricyanides are less toxic because they tend not to release free cyanide. It is of commercial interest as a precursor to the pigment Prussian blue and, as its potassium salt, an anticaking agent.

The history of gaseous fuel, important for lighting, heating, and cooking purposes throughout most of the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century, began with the development of analytical and pneumatic chemistry in the 18th century. The manufacturing process for "synthetic fuel gases" typically consisted of the gasification of combustible materials, usually coal, but also wood and oil. The coal was gasified by heating the coal in enclosed ovens with an oxygen-poor atmosphere. The fuel gases generated were mixtures of many chemical substances, including hydrogen, methane, carbon monoxide and ethylene, and could be burnt for heating and lighting purposes. Coal gas, for example, also contains significant quantities of unwanted sulfur and ammonia compounds, as well as heavy hydrocarbons, and so the manufactured fuel gases needed to be purified before they could be used.

In situ chemical reduction (ISCR) is a new type of environmental remediation technique used for soil and/or groundwater remediation to reduce the concentrations of targeted environmental contaminants to acceptable levels. It is the mirror process of In Situ Chemical Oxidation (ISCO). ISCR is usually applied in the environment by injecting chemically reductive additives in liquid form into the contaminated area or placing a solid medium of chemical reductants in the path of a contaminant plume. It can be used to remediate a variety of organic compounds, including some that are resistant to natural degradation.

The Windsor Street Gasworks was a coal gas and coke manufacturing site in Nechells, Birmingham. The works were constructed in 1846 for the Birmingham Gas Light and Coke Company adjacent to the Birmingham and Fazeley Canal to allow for the bulk import of coal. The company was taken over by the Birmingham Corporation in 1875 and under mayor Joseph Chamberlain and engineer Charles Hunt the Windsor Street site was expanded and connected to the London and North Western Railway. Hunt's works included the construction, in 1885, of gasholders No. 13 and No.14, the largest in the world at that time, as well as modernisation of production.

References

- ↑ "Warning as chemicals found in garden soil". Wolverhampton Express and Star. 12 December 2009.

- ↑ "Blue Billy". Early London Gas Industry. 7 August 2009.

- ↑ Clare Deanesly (30 September 2008). "Brownfield land and beating the Blue Billy blues". Lexology. Nabarro LLP.

- 1 2 3 "Soil and Groundwater Remediation Technologies for Former Gasworks and Gasholder Sites" (PDF). Celtic-EnGlobe. 2015. p. 34.

- ↑ "Gas Plant Wastes and Residuals". Former Manufactured Gas Plants.

- ↑ Dr. Russell Thomas. "Gas Purification". Parsons Brinckerhoff.

- 1 2 Jones, Richard; Reeve, Cyril G. (1978). A History of Gas Production in Wales. Wales Gas Printing Centre, British Gas Corporation. p. 174.

- 1 2 3 Lambton Coke Works: Remediation and Stabilisation. Vertase FLI. 2001.

- ↑ Hatheway, Fouled Wood-Shavings as "Box" Wastes

- ↑ Hatheway, Cyanogens and Lampblack

- ↑ "The remediation process". Grassmoor Lagoons. Avenue Coking Works, Grassmoor Colliery, Derbyshire. 2012.