Leiocephalidae, also known as the curlytail lizards or curly-tailed lizards, is a family of iguanian lizards restricted to the West Indies. One of the defining features of these lizards is that their tail often curls over. They were previously regarded as members of the subfamily Leiocephalinae within the family Tropiduridae. There are presently 30 known species, all in the genus Leiocephalus.

The Tropidophiidae, common name dwarf boas or thunder snakes, are a family of nonvenomous snakes found from Mexico and the West Indies south to southeastern Brazil. These are small to medium-sized fossorial snakes, some with beautiful and striking color patterns. Currently, two living genera, containing 34 species, are recognized. Two other genera were once considered to be tropidophiids but are now known to be more closely related to the boids, and are classified in the subfamily Ungaliophiinae. There are a relatively large number of fossil snakes that have been described as tropidophiids, but which of these are more closely related to Tropidophis and Trachyboa and which are more closely related to Ungaliophis and Exiliboa is unknown.

Marie-Galante is one of the dependencies of Guadeloupe, an overseas department of France. Marie-Galante has a land area of 158.1 km2. It had 11,528 inhabitants at the start of 2013, but by the start of 2018 the total was officially estimated to be 10,655, with a population density of 62.5/km2 (162/sq mi).

Guadeloupe is an archipelago of more than 12 islands, as well as islets and rocks situated where the northeastern Caribbean Sea meets the western Atlantic Ocean. It is located in the Leeward Islands in the northern part of the Lesser Antilles, a partly volcanic island arc. To the north lie Antigua and Barbuda and the British Overseas Territory of Montserrat, with Dominica lying to the south.

Palaeoloxodon falconeri is an extinct species of dwarf elephant from the Middle Pleistocene of Sicily and Malta. It is amongst the smallest of all dwarf elephants, under 1 metre (3.3 ft) in height as fully grown adults. A member of the genus Palaeoloxodon, it derived from a population of the mainland European straight-tusked elephant.

The Lesser Antillean macaw or Guadeloupe macaw is a hypothetical extinct species of macaw that is thought to have been endemic to the Lesser Antillean island region of Guadeloupe. In spite of the absence of conserved specimens, many details about the Lesser Antillean macaw are known from several contemporary accounts, and the bird is the subject of some illustrations. Austin Hobart Clark described the species on the basis of these accounts in 1905. Due to the lack of physical remains, and the possibility that sightings were of macaws from the South American mainland, doubts have been raised about the existence of this species. A phalanx bone from the island of Marie-Galante confirmed the existence of a similar-sized macaw inhabiting the region prior to the arrival of humans and was correlated with the Lesser Antillean macaw in 2015. Later that year, historical sources distinguishing between the red macaws of Guadeloupe and the scarlet macaw of the mainland were identified, further supporting its validity.

Boa imperator is a large and heavy-bodied arboreal species of nonvenomous, constrictor-type snake in the family Boidae. One of the most popular pet snakes in the world, B. imperator's native range is from Mexico through Central and South America, with local populations on several small Caribbean islands. It is commonly called the Central American boa, northern boa, Colombian boa, common boa and common northern boa.

Desmodus draculae is an extinct species of vampire bat that inhabited Central and South America during the Pleistocene, and possibly the early Holocene. It was 30% larger than its living relative the common vampire bat. Fossils and unmineralized subfossils have been found in Argentina, Mexico, Ecuador, Brazil, Venezuela, Belize, and Bolivia.

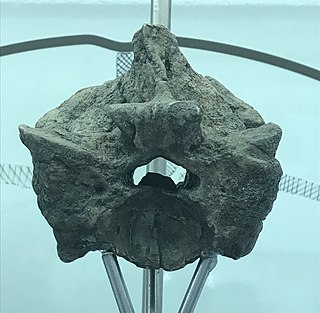

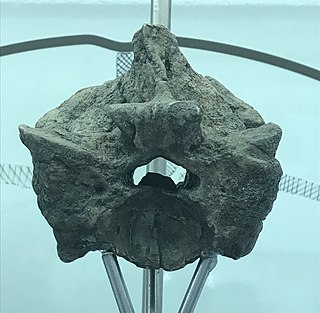

Titanoboa is an extinct genus of giant boid snake that lived during the middle and late Paleocene. Titanoboa was first discovered in the early 2000s by the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute who, along with students from the University of Florida, recovered 186 fossils of Titanoboa from La Guajira department in northeastern Colombia. It was named and described in 2009 as Titanoboa cerrejonensis, the largest snake ever found at that time. It was originally known only from thoracic vertebrae and ribs, but later expeditions collected parts of the skull and teeth. Titanoboa is in the subfamily Boinae, being most closely related to other extant boines from Madagascar and the Pacific.

The blunt-toothed giant hutia is an extinct species of giant hutia from Anguilla and Saint Martin that is estimated to have weighed between 50 and 200 kg. It was discovered by Edward Drinker Cope in 1868 in a sample of phosphate sediments mined in an unknown cave in Anguilla and sent to Philadelphia to estimate the value of the sediments. It is the sole species of the genus Amblyrhiza in the fossil family Heptaxodontidae.

"Ekbletomys hypenemus" is an extinct oryzomyine rodent from the islands of Antigua and Barbuda, Lesser Antilles. It was described as the only species of the subgenus "Ekbletomys" of genus Oryzomys in a 1962 Ph.D. thesis, but that name is not available under the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature and the species remains formally unnamed. It is currently referred to as "Ekbletomys hypenemus" in the absence of a formally available name. The species is now thought to be extinct, but association with introduced Rattus indicates that it survived until before 1500 BCE on Antigua.

Wezmeh Cave is an archaeological site near Islamabad Gharb, western Iran, around 470 km (290 mi) southwest of the capital Tehran. The site was discovered in 1999 and excavated in 2001 by a team of Iranian archaeologists under the leadership of Dr. Kamyar Abdi. Wezmeh cave was re-excavated by a team under direction of Fereidoun Biglari in 2019.

Homo luzonensis, also known as Callao Man and locally called "Ubag" after a mythical caveman, is an extinct, possibly pygmy, species of archaic human from the Late Pleistocene of Luzon, the Philippines. Their remains, teeth and phalanges, are known only from Callao Cave in the northern part of the island dating to before 50,000 years ago. They were initially identified as belonging to modern humans in 2010, but in 2019, after the discovery of more specimens, they were placed into a new species based on the presence of a wide range of traits similar to modern humans as well as to Australopithecus and early Homo. In 2023, a study found that the fossilized remains were 134,000 ± 14,000 years old, much older than previously thought.

The boa constrictor, also known as the common boa, is a species of large, non-venomous, heavy-bodied snake that is frequently kept and bred in captivity. The boa constrictor is a member of the family Boidae. The species is native to tropical South America. A staple of private collections and public displays, its color pattern is highly variable yet distinctive. Four subspecies are recognized.

The Conard Fissure is a geologic feature in Northern Arkansas where a deposit of Pleistocene fossils was discovered in 1903. Several specimens from saber-toothed cats were found there among other species.

The Red Deer Cave people were a prehistoric population of modern humans known from bones dated to between about 17,830 to c. 11,500 years ago, found in Red Deer Cave and Longlin Cave in Yunnan and Guangxi Provinces, in Southwest China.

Protopithecus is an extinct genus of large New World monkey that lived during the Pleistocene. Fossils have been found in the Toca da Boa Vista cave of Brazil, as well as other locales in the country. Fossils of another large, but less robust ateline monkey, Caipora, were also discovered in Toca da Boa Vista.

Kilu Cave is a paleoanthropological site located on Buka Island in the Autonomous Region of Bougainville, Papua New Guinea. Kilu Cave is located at the base of a limestone cliff, 65 m (213 ft) from the modern coastline. With evidence for human occupation dating back to 30,000 years, Kilu Cave is the earliest known site for human occupation in the Solomon Islands archipelago. The site is the oldest proof of paleolithic people navigating the open ocean i.e. navigating without land in sight. To travel from Nissan island to Buka requires crossing of at least 60 kilometers of open sea. The presence of paleolithic people at Buka therefore is at the same time evidence for the oldest and the longest paleolithic sea travel known so far.