Related Research Articles

The Ambrosian Rite is a Latin liturgical rite of the Catholic Church. The rite is named after Saint Ambrose, a bishop of Milan in the fourth century. It is used by around five million Catholics in the greater part of the Archdiocese of Milan, in some parishes of the Diocese of Como, Bergamo, Novara, Lodi, and in the Diocese of Lugano, Canton of Ticino, Switzerland.

The Mozarabic Rite, officially called the Hispanic Rite, and in the past also called the Visigothic Rite, is a liturgical rite of the Latin Church once used generally in the Iberian Peninsula (Hispania), in what is now Spain and Portugal. While the liturgy is often called 'Mozarabic' after the Christian communities that lived under Muslim rulers in Al-Andalus that preserved its use, the rite itself developed before and during the Visigothic period. After experiencing a period of decline during the Reconquista, when it was superseded by the Roman Rite in the Christian states of Iberia as part of a wider programme of liturgical standardization within the Catholic Church, efforts were taken in the 16th century to revive the rite and ensure its continued presence in the city of Toledo, where it is still celebrated today. It is also celebrated on a more widespread basis throughout Spain and, by special dispensation, in other countries, though only on special occasions.

In the Western Church of the Early and High Middle Ages, a sacramentary was a book used for liturgical services and the mass by a bishop or priest. Sacramentaries include only the words spoken or sung by him, unlike the missals of later centuries that include all the texts of the mass whether read by the bishop, priest, or others. Also, sacramentaries, unlike missals, include texts for services other than the mass such as ordinations, the consecration of a church or altar, exorcisms, and blessings, all of which were later included in Pontificals and Rituals instead.

A missal is a liturgical book containing instructions and texts necessary for the celebration of Mass throughout the liturgical year. Versions differ across liturgical tradition, period, and purpose, with some missals intended to enable a priest to celebrate Mass publicly and others for private and lay use. The texts of the most common Eucharistic liturgy in the world, the Catholic Church's Mass of Paul VI of the Roman Rite, are contained in the 1970 edition of the Roman Missal.

The so-called Gelasian Sacramentary is a book of Christian liturgy, containing the priest's part in celebrating the Eucharist. It is the second oldest western liturgical book that has survived: only the Verona Sacramentary is older.

The Gallican Rite is a historical form of Christian liturgy and other ritual practices in Western Christianity. It is not a single liturgical rite but rather several Latin liturgical rites that developed within the Latin Church, which comprised the majority use of most of Western Christianity for the greater part of the 1st millennium AD. The rites first developed in the early centuries as the Syriac-Greek rites of Jerusalem and Antioch and were first translated into Latin in various parts of the Western Roman Empire Praetorian prefecture of Gaul. By the 5th century, it was well established in the Roman civil diocese of Gaul, which had a few early centers of Christianity in the south. Ireland is also known to have had a form of this Gallican Liturgy mixed with Celtic customs.

The Roman Rite is the most common ritual family for performing the ecclesiastical services of the Latin Church, the largest of the sui iuris particular churches that comprise the Catholic Church. The Roman Rite governs rites such as the Roman Mass and the Liturgy of the Hours as well as the manner in which sacraments and blessings are performed.

The term "Celtic Rite" is applied to the various liturgical rites used in Celtic Christianity in Britain, Ireland and Brittany and the monasteries founded by St. Columbanus and Saint Catald in France, Germany, Switzerland, and Italy during the Early Middle Ages. The term is not meant to imply homogeneity; instead it is used to describe a diverse range of liturgical practices united by lineage and geography.

The Antiphonary of Bangor is an ancient Latin manuscript, supposed to have been originally written at Bangor Abbey in modern-day Northern Ireland.

Pre-Tridentine Mass refers to the evolving and regional forms of the Catholic Mass in the West from antiquity to 1570.

Latin liturgical rites, or Western liturgical rites, is a large family of liturgical rites and uses of public worship employed by the Latin Church, the largest particular church sui iuris of the Catholic Church, that originated in Europe where the Latin language once dominated. Its language is now known as Ecclesiastical Latin. The most used rite is the Roman Rite.

The Roman Canon is the oldest eucharistic prayer used in the Mass of the Roman Rite, and dates its arrangement to at least the 7th century; its core, however, is much older. Through the centuries, the Roman Canon has undergone minor alterations and modifications, but retains the same essential form it took in the seventh century under Pope Gregory I. Before 1970, it was the only eucharistic prayer used in the Roman Missal, but since then three other eucharistic prayers were newly composed for the Mass of Paul VI.

The Dominican Rite is the unique liturgical rite of the Dominican Order in the Catholic Church. It has been classified differently by different sources – some consider it a usage of the Roman Rite, others a variant of the Gallican Rite, and still others a form of the Roman Rite into which Gallican elements were inserted.

Station days were days of fasting in the early Christian Church, associated with a procession to certain prescribed churches in Rome, where the Mass and Vespers would be celebrated to mark important days of the liturgical year. Although other cities also had similar practices, and the fasting is no longer prescribed, the Roman churches associated with the various station days are still the object of pilgrimage and ritual, especially in the season of Lent.

The liturgical books of the Roman Rite are the official books containing the words to be recited and the actions to be performed in the celebration of Catholic liturgy as done in Rome. The Roman Rite of the Latin or Western Church of the Catholic Church is the most widely celebrated of the scores of Catholic liturgical rites. The titles of some of these books contain the adjective "Roman", e.g. the "Roman Missal", to distinguish them from the liturgical books for the other rites of the Church.

The Celtic mass is the liturgy of the Christian office of the Mass as it was celebrated within Celtic Rite of Celtic Christianity in the Early Middle Ages.

Yitzhak Hen is Anna and Sam Lopin Professor of History, formerly at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev (Israel). Since August 2018 he has been the director of Israel Institute for Advanced Studies at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

The Leofric Missal is an illuminated manuscript, not strictly a conventional missal, from the 10th and 11th century, now in the Bodleian Library at Oxford University where it is catalogued as MS Bodl. 579.

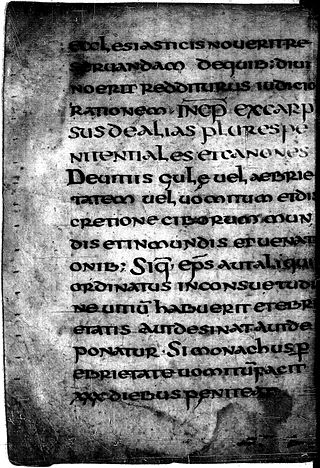

The Excarpsus Cummeani, also called the Pseudo-Cummeani, is an eighth-century penitential, probably written in the north of the Frankish Empire in Corbie Abbey. Twenty-six copies of the manuscript survive; six of those were copied before 800 CE. It is possible that the penitential, which extends its scope beyond monasticism to include clerics and lay people, has a connection to Saint Boniface and his efforts to reform the Frankish church in the first half of the eighth century. Geographic spread by the end of the eighth century and continued copying of the manuscript into the 9th and 10th centuries have been interpreted to mean the work was considered "by the Christian authorities" a canonical text. It was used as late as the eleventh century, "as the main source of the P. Parisiense compositum.

Robert Marie Joseph "Rob" Meens is a Dutch historian and professor at Utrecht University.

References

Notes

- 1 2 Hen & Meens 2004, p. 4.

- ↑ Hen & Meens 2004, p. 1.

- ↑ Frazier, Alison (September 2005). "Rev of Hen, Meens, Bobbio Missal". H-Net . Retrieved 22 August 2014.

- ↑ Hen & Meens 2004, pp. 22–23.

- ↑ Hen & Meens 2004, p. 23.

- 1 2 3 4 Hen & Meens 2004, pp. 9–15.

- ↑ "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: The Celtic Rite".

- 1 2 Hen & Meens 2004, p. 13.

- 1 2 3 Hen & Meens 2004, p. 51.

- ↑ Hen & Meens 2004, p. 59.

- ↑ Hen & Meens 2004, p. 66.

- ↑ Hen & Meens 2004, pp. 136–139.

- ↑ Hen & Meens 2004, pp. 152–53.

- ↑ Legg, J. Wickham, ed. (1917). The Bobbio missal, a Gallican Mass-book (ms. Paris. Lat. 13246). London: Henry Bradshaw Society.

Reference bibliography

- Hen, Yitzhak; Meens, Rob (2004). The Bobbio Missal: Liturgy and Religious Culture in Merovingian Gaul. Cambridge UP. ISBN 9780521823937.

External links

- Digital Images of the Bobbio Missal available from Gallica