Charles University, known also as Charles University in Prague or historically as the University of Prague, is the oldest and largest university in the Czech Republic. Founded in 1348, it was the first university in Central Europe. It is one of the oldest universities in Europe in continuous operation. Today, the university consists of 17 faculties located in Prague, Hradec Králové and Pilsen. Its academic publishing house is Karolinum Press. The university also operates several museums and two botanical gardens.

John the Blind was the count of Luxembourg from 1313 and king of Bohemia from 1310 and titular king of Poland. He is well known for having died while fighting in the Battle of Crécy at age 50, after having been blind for a decade.

Charles IV, born Wenceslaus, was the first King of Bohemia to become Holy Roman Emperor. He was a member of the House of Luxembourg from his father's side and the Czech House of Přemyslid from his mother's side; he emphasized the latter due to his lifelong affinity for the Czech side of his inheritance, and also because his direct ancestors in the Přemyslid line included two saints.

Ottokar I was Duke of Bohemia periodically beginning in 1192, then acquired the title King of Bohemia, first in 1198 from Philip of Swabia, later in 1203 from Otto IV of Brunswick and in 1212 from Frederick II. He was a member of the Přemyslid dynasty.

The scientific community is a diverse network of interacting scientists. It includes many "sub-communities" working on particular scientific fields, and within particular institutions; interdisciplinary and cross-institutional activities are also significant. Objectivity is expected to be achieved by the scientific method. Peer review, through discussion and debate within journals and conferences, assists in this objectivity by maintaining the quality of research methodology and interpretation of results.

The division between Czechs and Slovaks in Czechoslovakia persisted as a key element in the reform movement of the 1960s and the retrenchment of the 1970s, a decade that dealt harshly with the aspirations of both Czechs and Slovaks. Ethnicity still remained integral to the social, political, and economic affairs of the country. In 1968, a Slovak writer called for a more positive reappraisal of the Slovak Republic. Although as a Marxist he found Monsignor Jozef Tiso's "clerico-fascist state" politically abhorrent, he acknowledged that "the Slovak Republic existed as the national state of the Slovaks, the only one in our history..." Comparable sentiments surfaced periodically throughout the 1970s in letters to Bratislava's Pravda, even though the newspaper's editors tried to inculcate in their readership a "class and concretely historical approach" to the nationality question.

Roy Sydney Porter, FBA was a British historian known for his important work on the history of medicine. He retired in 2001 from the director of the Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine at University College London (UCL).

Josef Dobrovský was a Czech philologist and historian, one of the most important figures of the Czech National Revival along with Josef Jungmann.

František Palacký was a Czech historian and politician, the most influential person of the Czech National Revival, called "Father of the Nation".

The Lands of the Bohemian Crown, sometimes called Czech lands in modern times, were a number of incorporated states in Central Europe during the medieval and early modern periods connected by feudal relations under the Bohemian kings. The crown lands primarily consisted of the Kingdom of Bohemia, an electorate of the Holy Roman Empire according to the Golden Bull of 1356, the Margraviate of Moravia, the Duchies of Silesia, and the two Lusatias, known as the Margraviate of Upper Lusatia and the Margraviate of Lower Lusatia, as well as other territories throughout its history.

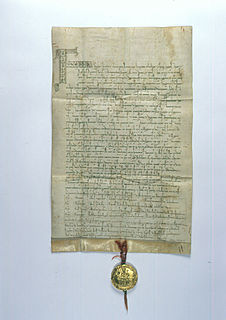

The Golden Bull of Sicily was a decree issued by Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor in Basel on 26 September 1212 that confirmed the royal title obtained by Ottokar I of Bohemia in 1198, declaring him and his heirs Kings of Bohemia. The kingship signified the exceptional status of Bohemia within the Holy Roman Empire.

Baron Carl von Rokitansky, was a Bohemian physician, pathologist, humanist philosopher and liberal politician.

The Merton thesis is an argument about the nature of early experimental science proposed by Robert K. Merton. Similar to Max Weber's famous claim on the link between Protestant work ethic and the capitalist economy, Merton argued for a similar positive correlation between the rise of Protestant Pietism and early experimental science. The Merton thesis has resulted in continuous debates.

The Czech National Revival was a cultural movement which took place in the Czech lands during the 18th and 19th centuries. The purpose of this movement was to revive the Czech language, culture and national identity. The most prominent figures of the revival movement were Josef Dobrovský and Josef Jungmann.

Royal Bohemian Society of Sciences was established in 1784 – originally without adjective "royal" which was granted as late as in 1790 by King and Emperor Leopold II – to be the scientific center for Lands of the Bohemian Crown. It was succeeded by the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences in 1952, and finally became what is known today as the Czech Academy of Sciences in 1992.

Dorothy Mary Moyle Needham FRS was an English biochemist known for her work on the biochemistry of muscle. She was married to biochemist Joseph Needham.

Josef Vratislav Monse was a Moravian lawyer and historian.

Societas eruditorum incognitorum in terris Austriacis was the first learned society in the lands under control of Austrian Habsburgs. It was established, formally, in 1746 at the university and episcopal town of Olomouc in order to spread Enlightenment ideas. Its monthly journal, "Monatliche Auszüge" was the first scientific journal in the Habsburg Monarchy.

Mikuláš Teich was a Slovak-British historian of science, best known for the series of histories in national context which he co-edited with Roy Porter. He was married to the economic historian Alice Teichova.

Slovakia in History is an edited collection of essays on the history of Slovakia in English published by Cambridge University Press in 2011, covering the period between the Duchy of Nitra in the first millennium and the 1993 dissolution of Czechoslovakia. The volume was edited by Cambridge University professor Mikuláš Teich and Dušan Kováč of the Slovak Academy of Sciences. Most of the contributors are historians with the Slovak Academy of Sciences. It received mixed reviews. James Mace Ward noted that book's coverage of twentieth-century history was much more in depth than its coverage of prior eras, and that non-Slovak peoples who lived in the territory of present-day Slovakia were ignored. The book was praised in Denník SME, which stated that it was the first time that an overview of Slovak history had been published by such a prestigious press in English and also felt that it was an evenhanded and objective book. However, Slovenské národné noviny criticized the book, arguing that the contributors were biased.