Anarcho-syndicalism is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that views revolutionary industrial unionism or syndicalism as a method for workers in capitalist society to gain control of an economy and thus control influence in broader society. The goal of syndicalism is to abolish the wage system, regarding it as wage slavery. Anarcho-syndicalist theory generally focuses on the labour movement. Reflecting the anarchist philosophy from which it draws its primary inspiration, anarcho-syndicalism is centred on the idea that power corrupts and that any hierarchy that cannot be ethically justified must be dismantled.

The Spanish Socialist Workers' Party is a social-democratic political party in Spain. The PSOE has been in government longer than any other political party in modern democratic Spain: from 1982 to 1996 under Felipe González, 2004 to 2011 under José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, and since 2018 under Pedro Sánchez.

The International Workers' Association – Asociación Internacional de los Trabajadores (IWA–AIT) is an international federation of anarcho-syndicalist labor unions and initiatives.

Anarchism in Spain has historically gained some support and influence, especially before Francisco Franco's victory in the Spanish Civil War of 1936–1939, when it played an active political role and is considered the end of the golden age of classical anarchism.

Andalusian nationalism is the nationalism that asserts that Andalusians are a nation and promotes the cultural unity of Andalusians. In the past it was considered to be represented primarily by the Andalusian Party. However, the party disbanded in 2015; there are also lesser political organisations that identify with Andalusian nationalism. Some political forces without parliamentary presence like Nación Andaluza and Asamblea Nacional de Andalucía may be found advocating independence. There is also a movement defending the idea that Andalusian is not a dialect of Spanish, but a language of its own.

The Confederación Nacional del Trabajo is a Spanish confederation of anarcho-syndicalist labor unions, which was long affiliated with the International Workers' Association (AIT). When working with the latter group it was also known as CNT-AIT. Historically, the CNT has also been affiliated with the Federación Anarquista Ibérica ; thus, it has also been referred to as the CNT-FAI. Throughout its history, it has played a major role in the Spanish labor movement.

Pistolerismo refers both to a specific period of Spanish history, between the general strike of August 1917 and Primo de Rivera's coup in September 1923, and to the social phenomenon spread in many areas of Spain during which Spanish employers hired thugs to face and often kill trade unionists and notable workers – and vice versa. It was characterized by the birth and proliferation of several armed groups composed of pistoleros, specialized men in the use of violence.

The Statute of Autonomy of Andalusia is a law hierarchically located under the 1978 Constitution of Spain, and over any legislation passed by the Andalusian Autonomous Government. During the Spanish transition to democracy, Andalusia was the one region of Spain to take its path to autonomy under what was called the "vía rápida" allowed for by Article 151 of the 1978 Constitution. That article was set out for regions like Andalusia that had been prevented by the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War from adopting a statute of autonomy during the period of the Second Spanish Republic. Following this procedure, Andalusia was constituted as an autonomous community February 28, 1980. The regional holiday of the Andalusia Day commemorates that date. The statute was approved the following year by the Spanish national government.

The Canadenca strike was a historic strike action in Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain, that was initiated in February 1919 by Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT) and lasted over 44 days evolving into a general strike paralyzing much of the industry of Catalonia. Among its consequences was to force the Spanish government to issue the Decreto de la jornada de ocho horas de trabajo, the first law limiting the working day to eight hours. The strike originated at the principal electricity company in Barcelona, Riegos y Fuerzas del Ebro, a subsidiary of Barcelona Traction, popularly known as la Canadenca because its major shareholder was the Canadian Bank of Commerce of Toronto.

The crisis of 1917 is the name that Spanish historians have given to the series of events that took place in the summer of 1917 in Spain. In particular, three simultaneous challenges threatened the government and the system of the Restoration: a military movement, a political movement and a social movement. These events coincided with a number of critical international events that same year. However, in world history this period is not typically referred to as a crisis, and the term is instead reserved for specific issues relating to World War I, such as the conscription crisis in Canada and the crisis of naval construction in the United States. Spain remained neutral throughout the conflict.

Isabel Mesa Delgado was a Spanish trade unionist, anarchist and Spanish anarcha-feminist worker. While in hiding, she used the pseudonym Carmen Delgado Palomares.

The Black Hand was a presumed secret, anarchist organization based in the Andalusian region of Spain and best known as the perpetrators of murders, arson, and crop fires in the early 1880s. The events associated with the Black Hand took place in 1882 and 1883 amidst class struggle in the Andalusian countryside, the spread of anarcho-communism distinct from collectivist anarchism, and differences between legalists and illegalists in the Federación de Trabajadores de la Región Española.

The anarchist insurrection of January 1933, also known as the January 1933 revolution, was the second of the insurrections carried out by the National Confederation of Labor (CNT) in the Second Spanish Republic, during the First Biennium.

The 1917 Spanish general strike, or revolutionary general strike of 1917, refers to the general strike that took place in Spain in August 1917. It was called by the General Union of Workers (UGT) and the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE), and in some places it was supported by the National Confederation of Labor (CNT). The general strike took place in the historical context of the Crisis of 1917, during the reign of Alfonso XIII and the government of Eduardo Dato.

The Federation of Workers of the Spanish Region was a Spanish anarchist organization founded in the Barcelona Workers' Congress of 1881 by the initiative of a group of Catalan anarcho-syndicalists headed Josep Llunas i Pujals, Rafael Farga Pellicer and Antoni Pellicer, after the dissolution of the Spanish Regional Federation of the International Workingmen's Association founded in the Barcelona Workers' Congress of 1870. It only had seven years of life since it was dissolved in 1888. Its failure, in which the episode of La Mano Negra was key, opened a new stage in the history of anarchism in Spain dominated by propaganda of the deed.

The Seville Congress was the Second Congress of the newly created Federation of Workers of the Spanish Region held in Seville in September 1882.

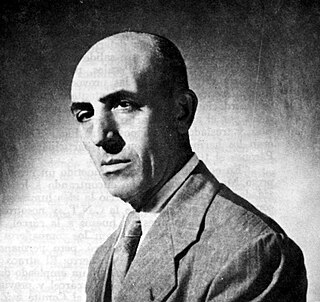

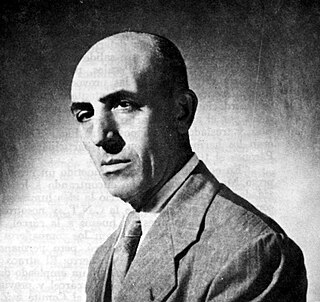

Evelio Boal López was a Spanish graphic designer, trade unionist and anarchist. He was one of the organizers of the Congress of Sants of the National Confederation of Labor, forming part of the commission that wrote the report.

Paulino Díez Martín was a Spanish anarcho-syndicalist leader. He wrote Una anarcosindicalista en acción. Memorias.

The Riotinto-Nerva mining basin is a Spanish mining area located in the northeast of the province of Huelva (Andalusia), which has its main population centers in the municipalities of El Campillo, Minas de Riotinto and Nerva, in the region of the Cuenca Minera. It is also part of the Iberian Pyrite Belt.

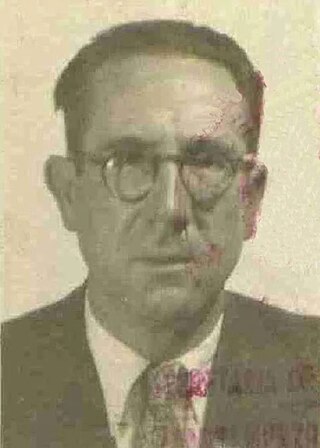

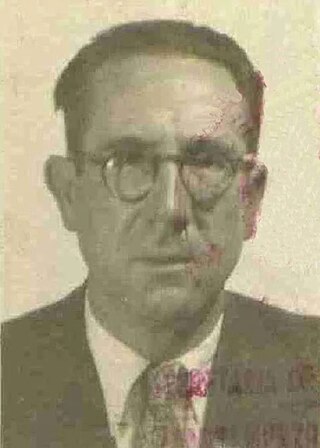

Manuel Adame Misa (1901–1945) was an Andalusian trade unionist and politician. Initially an anarcho-syndicalist of the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT), in 1927, he became a leading member of the Communist Party of Spain (PCE) in Andalusia. In 1932, he was ejected from the PCE, due to his conflicts with the leadership of the Communist International, and subsequently joined the Unión General de Trabajadores (UGT) and Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE). He was active in the Republican side of the Spanish Civil War and, after its defeat, fled to Mexico, where he died.