Monza is a city and comune on the River Lambro, a tributary of the Po in the Lombardy region of Italy, about 15 kilometres north-northeast of Milan. It is the capital of the Province of Monza and Brianza. Monza is best known for its Grand Prix motor racing circuit, the Autodromo Nazionale di Monza, which hosts the Formula One Italian Grand Prix with a massive Italian support tifosi for the Ferrari team.

Theodelinda also spelled Theudelinde, was a queen of the Lombards by marriage to two consecutive Lombard rulers, Autari and then Agilulf, and regent of Lombardia during the minority of her son Adaloald, and co-regent when he reached majority, from 616 to 626. For well over thirty years, she exercised influence across the Lombard realm, which comprised most of Italy between the Apennines and the Alps. Born a Frankish Catholic, she convinced her first spouse Autari to convert from pagan beliefs to Christianity.

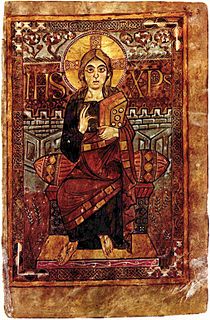

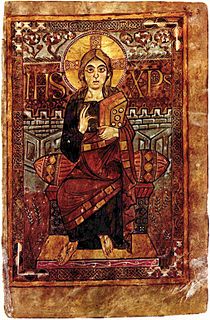

The Book of Kells is an illuminated manuscript Gospel book in Latin, containing the four Gospels of the New Testament together with various prefatory texts and tables. It was created in a Columban monastery in either Scotland, England or Ireland and may have had contributions from various Columban institutions from each of these areas. It is believed to have been created c. 800 AD. The text of the Gospels is largely drawn from the Vulgate, although it also includes several passages drawn from the earlier versions of the Bible known as the Vetus Latina. It is a masterwork of Western calligraphy and represents the pinnacle of Insular illumination. It is also widely regarded as one of Ireland's finest national treasures. The manuscript takes its name from the Abbey of Kells, which was its home for centuries.

The St Cuthbert Gospel, also known as the Stonyhurst Gospel or the St Cuthbert Gospel of St John, is an early 8th-century pocket gospel book, written in Latin. Its finely decorated leather binding is the earliest known Western bookbinding to survive, and both the 94 vellum folios and the binding are in outstanding condition for a book of this age. With a page size of only 138 by 92 millimetres, the St Cuthbert Gospel is one of the smallest surviving Anglo-Saxon manuscripts. The essentially undecorated text is the Gospel of John in Latin, written in a script that has been regarded as a model of elegant simplicity.

The Book of Durrow is a medieval illuminated manuscript gospel book in the Insular script style. It was probably created between 650 and 700. The place of creation may perhaps have been Durrow Abbey in Ireland or a monastery in Northumbria in northeastern England or perhaps Iona Abbey in western Scotland—the place of origin has been debated by historians for decades without a consensus emerging. The Book of Durrow was probably at Durrow Abbey by 916. Today it is in the Library of Trinity College Dublin.

The Lichfield Gospels is an 8th century Insular Gospel Book housed in Lichfield Cathedral. There are 236 surviving pages, eight of which are illuminated. Another four contain framed text. The pages measure 30.8 cm by 23.5 cm. The manuscript is also important because it includes, as marginalia, some of the earliest known examples of written Old Welsh, dating to the early part of the 8th century. Peter Lord dates the book at 730, placing it chronologically before the Book of Kells but after the Lindisfarne Gospels.

The Godescalc Evangelistary, Godescalc Sacramentary, Godescalc Gospels, or Godescalc Gospel Lectionary is an illuminated manuscript in Latin made by the Frankish scribe Godescalc and today kept in the Bibliothèque nationale de France. It was commissioned by the Carolingian king Charlemagne and his wife Hildegard on October 7, 781 and completed on April 30, 783. The Evangelistary is the earliest known manuscript produced at the scriptorium in Charlemagne's Court School in Aachen. The manuscript was intended to commemorate Charlemagne's march to Italy, his meeting with Pope Adrian I, and the baptism of his son Pepin. The crediting of the work to Godescalc and the details of Charlemagne's march are contained in the manuscript's dedication poem.

A cumdach or book shrine is an elaborate ornamented box or case used as a reliquary to enshrine books regarded as relics of the saints who had used them in Early Medieval Ireland. They are normally later than the book they contain, often by several centuries, typically the book comes from the heroic age of Irish monasticism before 800, and the surviving cumdachs date from after 1000, although it is clear the form dates from considerably earlier. Several were then considerably reworked in the Gothic period. The usual form is a design based on a cross on the main face, with use of large gems of rock crystal or other semi-precious stones, leaving the spaces between the arms of the cross for more varied decoration. Several were carried on a chain or cord, often suspended round the neck, which by placing them next to the heart was believed to bring spiritual and perhaps medical benefits. They were also used to witness contracts. Many had hereditary lay keepers from among the chiefly families who had formed links with monasteries. Most surviving examples are now in the National Museum of Ireland ("NMI").

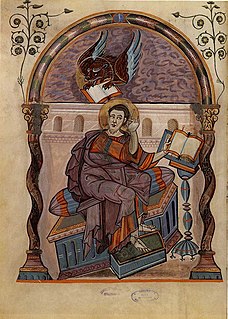

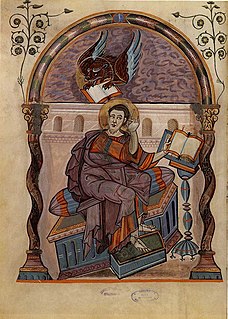

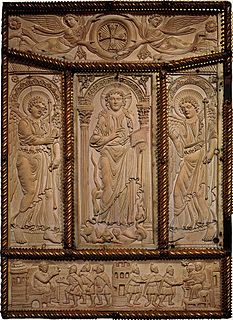

Evangelist portraits are a specific type of miniature included in ancient and mediaeval illuminated manuscript Gospel Books, and later in Bibles and other books, as well as other media. Each Gospel of the Four Evangelists, the books of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, may be prefaced by a portrait of the Evangelist, usually occupying a full page. Their symbols may be shown with them, or separately. Often they are the only figurative illumination in the manuscript. They are a common feature in larger Gospel Books from the earliest examples in the 6th century until the decline of that format for illustrated books in the High Middle Ages, by which time their conventions were being used for portraits of other authors.

Anglo-Saxon art covers art produced within the Anglo-Saxon period of English history, beginning with the Migration period style that the Anglo-Saxons brought with them from the continent in the 5th century, and ending in 1066 with the Norman Conquest of a large Anglo-Saxon nation-state whose sophisticated art was influential in much of northern Europe. The two periods of outstanding achievement were the 7th and 8th centuries, with the metalwork and jewellery from Sutton Hoo and a series of magnificent illuminated manuscripts, and the final period after about 950, when there was a revival of English culture after the end of the Viking invasions. By the time of the Conquest the move to the Romanesque style is nearly complete. The important artistic centres, in so far as these can be established, were concentrated in the extremities of England, in Northumbria, especially in the early period, and Wessex and Kent near the south coast.

Carolingian art comes from the Frankish Empire in the period of roughly 120 years from about 780 to 900—during the reign of Charlemagne and his immediate heirs—popularly known as the Carolingian Renaissance. The art was produced by and for the court circle and a group of important monasteries under Imperial patronage; survivals from outside this charmed circle show a considerable drop in quality of workmanship and sophistication of design. The art was produced in several centres in what are now France, Germany, Austria, northern Italy and the Low Countries, and received considerable influence, via continental mission centres, from the Insular art of the British Isles, as well as a number of Byzantine artists who appear to have been resident in Carolingian centres.

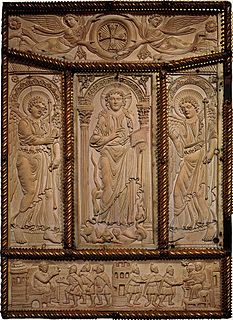

Ottonian art is a style in pre-romanesque German art, covering also some works from the Low Countries, northern Italy and eastern France. It was named by the art historian Hubert Janitschek after the Ottonian dynasty which ruled Germany and northern Italy between 919 and 1024 under the kings Henry I, Otto I, Otto II, Otto III and Henry II. With Ottonian architecture, it is a key component of the Ottonian Renaissance. However, the style neither began nor ended to neatly coincide with the rule of the dynasty. It emerged some decades into their rule and persisted past the Ottonian emperors into the reigns of the early Salian dynasty, which lacks an artistic "style label" of its own. In the traditional scheme of art history, Ottonian art follows Carolingian art and precedes Romanesque art, though the transitions at both ends of the period are gradual rather than sudden. Like the former and unlike the latter, it was very largely a style restricted to a few of the small cities of the period, and important monasteries, as well as the court circles of the emperor and his leading vassals.

Romanesque art is the art of Europe from approximately 1000 AD to the rise of the Gothic style in the 12th century, or later, depending on region. The preceding period is known as the Pre-Romanesque period. The term was invented by 19th-century art historians, especially for Romanesque architecture, which retained many basic features of Roman architectural style – most notably round-headed arches, but also barrel vaults, apses, and acanthus-leaf decoration – but had also developed many very different characteristics. In Southern France, Spain and Italy there was an architectural continuity with the Late Antique, but the Romanesque style was the first style to spread across the whole of Catholic Europe, from Sicily to Scandinavia. Romanesque art was also greatly influenced by Byzantine art, especially in painting, and by the anti-classical energy of the decoration of the Insular art of the British Isles. From these elements was forged a highly innovative and coherent style.

Castelseprio or Castel Seprio was the site of a Roman fort in antiquity, and a significant Lombard town in the early Middle Ages, before being destroyed and abandoned in 1287. It is today preserved as an archaeological park in the modern comune of Castelseprio, near the modern village of the same name. It is in the north of Italy, in the Province of Varese, about 50 km northwest of Milan.

The Evangeliary or Book of the Gospels is a liturgical book containing only those portions of the four gospels which are read during Mass or in other public offices of the Church. The corresponding terms in Latin are Evangeliarium and Liber evangeliorum.

Insular art, also known as Hiberno-Saxon art, was produced in the post-Roman history of Ireland and Britain. The term derives from insula, the Latin term for "island"; in this period Britain and Ireland shared a largely common style different from that of the rest of Europe. Art historians usually group insular art as part of the Migration Period art movement as well as Early Medieval Western art, and it is the combination of these two traditions that gives the style its special character.

The Duomo of Monza often known in English as Monza Cathedral is the main religious building of Monza, in northern Italy. Unlike most duomos it is not in fact a cathedral, as Monza has always been part of the Diocese of Milan, but is in the charge of an archpriest who has the right to certain episcopal vestments including the mitre and the ring. The church is also known as the Basilica of San Giovanni Battista from its dedication to John the Baptist.

In ecclesiastical architecture, a ciborium is a canopy or covering supported by columns, freestanding in the sanctuary, that stands over and covers the altar in a basilica or other church. It may also be known by the more general term of baldachin, though ciborium is often considered more correct for examples in churches. Really a baldachin should have a textile covering, or at least, as at Saint Peter's in Rome, imitate one. There are exceptions; Bernini's structure in Saint Peter's, Rome is always called the "baldachin". Early ciboria had curtains hanging from rods between the columns, so that the altar could be concealed from the congregation at points in the liturgy. Smaller examples may cover other objects in a church. In a very large church, a ciborium is an effective way of visually highlighting the altar, and emphasizing its importance. The altar and ciborium are often set upon a dais to raise it above the floor of the sanctuary.

In the visual arts, interlace is a decorative element found in medieval art. In interlace, bands or portions of other motifs are looped, braided, and knotted in complex geometric patterns, often to fill a space. Interlacing is common in the Migration period art of Northern Europe, especially in the Insular art of Ireland and the British Isles and Norse art of the Early Middle Ages and in Islamic art.

The Monza ampullae form the largest collection of a specific type of Early Medieval pilgrimage ampullae or small flasks designed to hold holy oil from pilgrimage sites in the Holy Land related to the life of Jesus. They were made in Palestine, probably in the fifth to early seventh centuries, and have been in the Treasury of Monza Cathedral north of Milan in Italy since they were donated by Theodelinda, queen of the Lombards,. Since the great majority of surviving examples of such flasks are those in the Monza group, the term may be used to cover this type of object in general.