The Massachusetts Bay Colony (1628–1691), more formally the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, was an English settlement on the east coast of North America around the Massachusetts Bay, one of the several colonies later reorganized as the Province of Massachusetts Bay. The lands of the settlement were in southern New England, with initial settlements on two natural harbors and surrounding land about 15.4 miles (24.8 km) apart—the areas around Salem and Boston, north of the previously established Plymouth Colony. The territory nominally administered by the Massachusetts Bay Colony covered much of central New England, including portions of Massachusetts, Maine, New Hampshire, and Connecticut.

Anne Hutchinson was a Puritan spiritual advisor, religious reformer, and an important participant in the Antinomian Controversy which shook the infant Massachusetts Bay Colony from 1636 to 1638. Her strong religious formal declaration were at odds with the established Puritan clergy in the Boston area and her popularity and charisma helped create a theological schism that threatened the Puritan religious community in New England. She was eventually tried and convicted, then banished from the colony with many of her supporters.

Richard Bellingham was a colonial magistrate, lawyer, and several-time governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, and the last surviving signatory of the colonial charter at his death. A wealthy lawyer in Lincolnshire prior to his departure for the New World in 1634, he was a liberal political opponent of the moderate John Winthrop, arguing for expansive views on suffrage and lawmaking, but also religiously somewhat conservative, opposing the efforts of Quakers and Baptists to settle in the colony. He was one of the architects of the Massachusetts Body of Liberties, a document embodying many sentiments also found in the United States Bill of Rights.

John Endecott, regarded as one of the Fathers of New England, was the longest-serving governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, which became the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. He served a total of 16 years, including most of the last 15 years of his life. When not serving as governor, he was involved in other elected and appointed positions from 1628 to 1665 except for the single year of 1634.

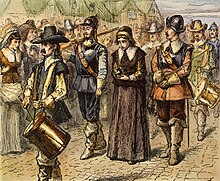

Mary Dyer was an English and colonial American Puritan-turned-Quaker who was hanged in Boston, Massachusetts Bay Colony, for repeatedly defying a Puritan law banning Quakers from the colony due to their theological expansion of the Puritan concept of a church of individuals regenerated by the Holy Spirit to the idea of the indwelling of the Spirit or the "Light of Christ" in every person, which was deemed dangerous heresy. She is one of the four executed Quakers known as the Boston martyrs.

Quakers are members of a Christian religious movement that started in England as a form of Protestantism in the 17th century, and has spread throughout North America, Central America, Africa, and Australia. Some Quakers originally came to North America to spread their beliefs to the British colonists there, while others came to escape the persecution they experienced in Europe. The first known Quakers in North America arrived in the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1656 via Barbados, and were soon joined by other Quaker preachers who converted many colonists to Quakerism. Many Quakers settled in the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, due to its policy of religious freedom, as well as the British colony of Pennsylvania which was formed by William Penn in 1681 as a haven for persecuted Quakers.

Christopher Holder (1631–1688) was an early Quaker evangelist who was imprisoned and whipped, had an ear cut off, and was threatened with death for his religious activism in the Massachusetts Bay Colony and in England. A native of Gloucestershire, near Bristol in western England, Holder became an early convert to the Society of Friends, and in 1656, at the age of 25, made his first voyage to New England aboard the Speedwell to spread his Quaker message. All of the Quakers in his group were imprisoned, and then sent back to England on the same ship. Undeterred, Holder returned to New England aboard the small barque Woodhouse, landing in New Amsterdam in August 1657 despite few predictions of success. Though young, he was a leader among the eleven Quaker missionaries that fanned out among the American colonies. Holder, with his frequent companion John Copeland, went north to begin their evangelistic efforts in the face of increasingly threatening anti-Quaker laws. With little success on Martha's Vineyard, they moved to Cape Cod in the Plymouth Colony where they were warmly received in Sandwich, establishing the earliest Quaker meeting in America.

The Puritan migration to New England took place from 1620 to 1640, declining sharply afterwards. The term "Great Migration" can refer to the migration in the period of English Puritans to the New England Colonies, starting with Plymouth Colony and Massachusetts Bay Colony. They came in family groups rather than as isolated individuals and were mainly motivated by freedom to practice their beliefs.

Nicholas Upsall was an early Puritan immigrant to the American Colonies, among the first 108 Freemen in colonial America. He was a trusted public servant who after 26 years as a Puritan, befriended persecuted Quakers and shortly afterwards joined the movement. He was banished from Massachusetts at 60 years of age and helped to found the first Monthly meeting of Friends in the United States at Sandwich, Massachusetts.

William Brenton was a colonial British statesman who served as colonial President, Deputy Governor, and Governor of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, and an early settler of Portsmouth and Newport in the Rhode Island colony. Believed to be from Hammersmith, Middlesex, England, he emigrated to the British Colonies in North America by 1633, and rose to minor prominence in the Massachusetts Bay Colony before relocating to a new settlement to the south that became today's Rhode Island.

Major-General Humphrey Atherton, an early settler of Dorchester, Massachusetts, held the highest military rank in colonial New England. He first appeared in the records of Dorchester on March 18, 1637 and made freeman May 2, 1638. He became a representative in the General Court in 1638 and 1639–41. In 1653, he was Speaker of the House, representing Springfield, Massachusetts. He was chosen assistant governor, a member of the lower house of the General Court who also served as magistrate in the judiciary of colonial government, in 1654, and remained as such until his death." He was a member of the Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company of Massachusetts and held the ranks of lieutenant and captain for several years before rising to the rank of major-general. He also organized the first militia in Massachusetts.

William Dyer was an early settler of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, a founding settler of both Portsmouth and Newport, and Rhode Island's first Attorney General. He is also notable for being the husband of the Quaker martyr Mary Dyer, who was executed for her Quaker activism. Sailing from England as a young man with his wife, Dyer first settled in Boston in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, but like many members of the Boston church, he became a supporter of the dissident ministers John Wheelwright and Anne Hutchinson during the Antinomian Controversy, and signed a petition in support of Wheelwright. For doing this, he was disenfranchised and disarmed, and with many other supporters of Hutchinson, he signed the Portsmouth Compact, and settled on Aquidneck Island in the Narragansett Bay. Within a year of arriving there, he and others followed William Coddington to the south end of the island, where they established the town of Newport.

Wenlock Christison was the last person to be sentenced to death in the Massachusetts Bay Colony for being a Quaker. Four people had previously been executed in Massachusetts for this reason. However, Christison was not executed. He left Massachusetts and lived the remainder of his life in Talbot County, Maryland.

John Wilson was a Puritan clergyman in Boston in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, and the minister of the First Church of Boston from its beginnings in Charlestown in 1630 until his death in 1667. He is most noted for being a minister at odds with Anne Hutchinson during the Antinomian Controversy from 1636 to 1638, and for being an attending minister during the execution of Mary Dyer in 1660.

General James Cudworth was one of the most important men in Plymouth Colony. He served as Deputy to the Plymouth General Court (1649), Commander of militia in King Philip's War (1675–8), Assistant Governor and Deputy Governor (1681–2) of Plymouth Colony, and Commissioner to the New England Confederation.

Speedwell could refer to the following ships:

Zechariah Symmes was an English Puritan clergyman who emigrated to the Massachusetts Bay Colony in New England and became pastor of the First Church in Charlestown, an office he held continuously from 1634 to his death in 1671. Although not one of the original Charlestown founders of 1629, on arrival in 1634 he swiftly found his place among them in the church they had convened two years previously. One of the many emigrant ministers who emerged from Emmanuel College, Cambridge, he was a close fellow-worker among the leading lights of the "Bible Commonwealth".

Katherine Marbury Scott was a Quaker advocate and colonist of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Like her older sister, Anne Hutchinson, she was persecuted by the Puritans when her open opposition to Puritan authorities disturbed the patriarchal order of the colony.

Sarah Gibbons was an English Quaker preacher in America. She was one of the first to land and she was initially imprisoned and banished. She returned and died in an accident in 1659.

Dorothy Waugh was an English Quaker preacher who was twice a missionary to North America. She wrote a rare account of the use of a Scold's bridle during one of her many imprisonments.