Related Research Articles

The 1926 General Strike in the United Kingdom was a general strike that lasted nine days, from 4 to 12 May 1926. It was called by the General Council of the Trades Union Congress (TUC) in an unsuccessful attempt to force the British government to act to prevent wage reductions and worsening conditions for 1.2 million locked-out coal miners. Some 1.7 million workers went out, especially in transport and heavy industry.

Ernest Bevin was a British statesman, trade union leader and Labour Party politician. He cofounded and served as General Secretary of the powerful Transport and General Workers' Union from 1922 to 1940 and served as Minister of Labour and National Service in the wartime coalition government. He succeeded in maximising the British labour supply for both the armed services and domestic industrial production with a minimum of strikes and disruption.

Sir Richard Stafford Cripps was a British Labour Party politician, barrister, and diplomat.

Walter McLennan Citrine, 1st Baron Citrine, was one of the leading British and international trade unionists of the twentieth century and a notable public figure. Yet, apart from his renowned guide to the conduct of meetings, ABC of Chairmanship, he has been little spoken of in the history of the labour movement. More recently, labour historians have begun to re-assess Citrine's role.

Clement Attlee was invited by King George VI to form the Attlee ministry in the United Kingdom in July 1945, succeeding Winston Churchill as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. The Labour Party had won a landslide victory at the 1945 general election, and went on to enact policies of what became known as the post-war consensus, including the establishment of the welfare state and the nationalisation of 20 percent of the entire economy. The government's spell in office was marked by post-war austerity measures; the crushing of pro-independence and communist movements in Malaya; the grant of independence to India, Pakistan, Ceylon, and Burma; the engagement in the Cold War against Soviet Communism; and the creation of the country's National Health Service (NHS).

John Emerson Harding Harding-Davies, was a British businessman who served as director-general of the Confederation of British Industry during the 1960s. He later went into politics and served in the Cabinet of Edward Heath as the first Secretary of State for Trade and Industry, a position which he held from October 1970 to 4 November 1972. Davies was President of the Board of Trade, and from July to October 1970 was Minister of Technology. He became a Privy Councillor and, in 1972, was appointed Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster with special responsibilities for the co-ordination of British policy towards the European Communities. In 1979 Davies was to be made a life peer as Baron Harding-Davies, but died before the creation of the peerage passed the Great Seal. Peerage history was made when, by Royal Warrant bearing the date 27 February 1980, Queen Elizabeth II granted his widow Vera Georgina the title of Lady Harding-Davies; his children Frank Davies and Rosamond Ann Metherell were given the rank of children of a life peer.

Trade unions in Ghana first emerged in the 1920s and have played an important role in the country's economy and politics ever since.

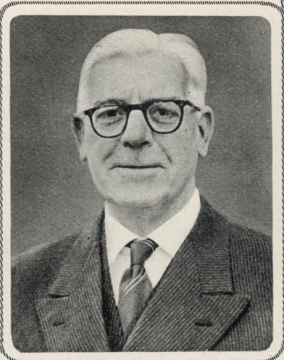

Charles John Geddes, Baron Geddes of Epsom, CBE was a British trade unionist.

Thomas Williamson, Baron Williamson, was a British trade unionist and Labour Party politician.

Arthur Cecil Allen was a British footwear manufacturer, trade union officer and Member of Parliament. He served as an Opposition Whip, but his most important position was as Parliamentary Private Secretary to Hugh Gaitskell during the first few years as Leader of the Opposition.

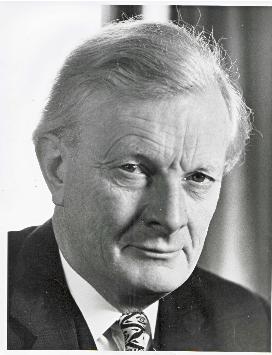

Sir William Owen Campbell Adamson was a British industrialist, who was best known for his work as director-general of the Confederation of British Industry (CBI) from 1969 to 1976. He rose through the steel industry, where he was in charge of labour relations, and worked as a government adviser during the late 1960s.

Doctors in Unite is a trade union for doctors in the United Kingdom. It was formerly known as the Medical Practitioners' Union (MPU) before its affiliation with Unite.

The Cotton Board was an organisation to oversee the organisation, research, marketing and promoting the cotton textile industry mainly based in Lancashire and Glasgow. It existed from 1940, and as a statutory Industrial Development Board from 1948 to 1972, known in its last years as the Textile Council.

The Industrial Organisation and Development Act 1947 enabled the creation of industrial development boards with powers to raise levies from specific industrial sectors in the United Kingdom for co-ordinated action, particularly in research, marketing and industrial re-organisation. These Boards were to report to the Board of Trade and have equal representation from trades unions and employers alongside independent experts.

The Ghana Trades Union Congress is a national centre that unites various workers' organizations in Ghana. The organization was established in 1945.

Frank Wolstencroft CBE was a British trade union leader.

The following events occurred in April 1948:

John Edward Newton was a British trade unionist.

The General Council of the Trades Union Congress is an elected body which is responsible for carrying out the policies agreed at the annual British Trade Union Congresses (TUC).

Frederic John Trump was a businessman and Republican candidate in the 1956 Arizona gubernatorial election. Between 1956 and 1960, he corresponded with then-vice president of the United States Richard Nixon. He was claimed to be a cousin of John G. Trump, brother of New York real-estate developer Fred Trump.

References

- ↑ "Anglo-American Council on Productivity Pamphlets Collection Number: 5334". Cornell University Library . Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- 1 2 "British Productivity Council". Warwick University . Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Anthony Carew (January 1991). "The Anglo-American Council on Productivity (1948-52): The Ideological Roots of the Post-War Debate on Productivity in Britain". Journal of Contemporary History . 26 (1): 49–69. doi:10.1177/002200949102600103. JSTOR 260630. S2CID 153766524 . Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ↑ "Anglo-American Council Of Productivity - Volume 469: 8 November 1949". Hansard . Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- ↑ Carl H. Gottwald (1999). The Anglo-American Council on Productivity: 1948-1952 British productivity and the Marshall Plan. University of North Texas. p. 15.

- ↑ "Economic Situation - Volume 507: 10 November 1952". Hansard . Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- ↑ Industry in Britain: Organisation and Production. British Information Services. November 1964. p. 18.

- ↑ "National Coal Board (Annual Report) - Volume 531: 25 October 1954". Hansard . Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- 1 2 Parliamentary Debates (Hansard).: House of Commons official report. H.M. Stationery Office. 1959. p. 1007.

- ↑ "NEW PRODUCTIVITY COUNCIL: Sir Peter Bennett Chairman". The Guardian . 5 November 1952. p. 10.

- ↑ Cook, Chris, ed. (2012). The Routledge Guide to British Political Archives. Routledge. p. 35. ISBN 9781136509629 . Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- 1 2 "Freight Movement and Handling - Volume 200: 13 November 1956". Hansard . Retrieved 16 October 2023.

- ↑ "Rising Productivity in Britain: Work of the British Productivity Council and the Trade Unions". Labor and Industry in Britain. 13: 60–66. 1955. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ↑ Bellamy, Joyce; Martin, David; Saville, John, eds. (15 January 1993). Dictionary of Labour Biography, Volume 9. Springer. ISBN 9781349078455 . Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- ↑ "HUTTON, Lt Gen Sir Thomas Jacomb (1890-1981)". JISC Archive Hub. Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- 1 2 3 Derrick Page (February 1993). "SPECIAL STAMP ISSUE National Productivity Year" (PDF). Postal Museum . Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ↑ "Sir Ewart - A leader in the art of good management". New Scientist : 1076. 14 May 1959. Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- ↑ "Bertram White". Grace's Guide to British Industrial History. Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- 1 2 "Quality And Reliability Year - Volume 277: 26 October 1966". Hansard . Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- ↑ R. P. McCormick (March 1962). "General Notes". Journal of the Royal Society of Arts . 110 (5068): 264–268. JSTOR 41367089 . Retrieved 3 January 2022.

- ↑ "NATIONAL PRODUCTIVITY YEAR". Parliament.uk . 12 July 1962. Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- ↑ "British Productivity Council". British Film Institute . Archived from the original on July 13, 2019. Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- ↑ "Time and Motion Study Volume 5 Issue 2". Work Study. 5 (2): 11–59. 1956. doi:10.1108/eb048085 . Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- ↑ John Cole (26 April 1961). "BBC and ITV reject film on strikes". The Guardian . p. 13.

- ↑ "Current Non-Fiction and Short Films". The Monthly Film Bulletin . 27 (312): 27. 1 January 1960.

- ↑ Russell, Patrick; Piers Taylor, James, eds. (2019). Shadows of Progress: Documentary Film in Post-War Britain. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1838718121.

- ↑ "Portrait of the Week". The Spectator . No. 7026. 22 February 1963. p. 215.