Excalibur is the mythical sword of King Arthur that may possess magical powers or be associated with the rightful sovereignty of Britain. Traditionally, the sword in the stone is the proof of Arthur's lineage. The sword given to him by the Lady of the Lake is not the same weapon, even though in some versions of the legend both of them share the name of Excalibur. Several similar swords and other weapons also appear within Arthurian texts, as well as in other legends.

Old English literature refers to poetry and prose written in Old English in early medieval England, from the 7th century to the decades after the Norman Conquest of 1066, a period often termed Anglo-Saxon England. The 7th-century work Cædmon's Hymn is often considered as the oldest surviving poem in English, as it appears in an 8th-century copy of Bede's text, the Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Poetry written in the mid 12th century represents some of the latest post-Norman examples of Old English. Adherence to the grammatical rules of Old English is largely inconsistent in 12th-century work, and by the 13th century the grammar and syntax of Old English had almost completely deteriorated, giving way to the much larger Middle English corpus of literature.

Layamon or Laghamon – spelled Laȝamon or Laȝamonn in his time, occasionally written Lawman – was an English poet of the late 12th/early 13th century and author of the Brut, a notable work that was the first to present the legends of Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table in English poetry.

Nennius – or Nemnius or Nemnivus – was a Welsh monk of the 9th century. He has traditionally been attributed with the authorship of the Historia Brittonum, based on the prologue affixed to that work. This attribution is widely considered a secondary (10th-century) tradition.

Middle English Bible translations covers the age of Middle English, beginning after the Norman Conquest (1066) and ending about 1500.

Historia regum Britanniae, originally called De gestis Britonum, is a fictitious historical account of British history, written around 1136 by Geoffrey of Monmouth. It chronicles the lives of the kings of the Britons over the course of two thousand years, beginning with the Trojans founding the British nation and continuing until the Anglo-Saxons assumed control of much of Britain around the 7th century. It is one of the central pieces of the Matter of Britain.

Guy of Warwick, or Gui de Warewic, is a legendary English hero of Romance popular in England and France from the 13th to 17th centuries, but now largely forgotten. The story of Sir Guy is considered by scholars to be part of the Matter of England.

Geoffrey Gaimar, also written Geffrei or Geoffroy, was an Anglo-Norman chronicler. His contribution to medieval literature and history was as a translator from Old English to Anglo-Norman. His L'Estoire des Engleis, or History of the English People, written about 1136–1140, was a chronicle in eight-syllable rhyming couplets, running to 6,526 lines.

Historians in England during the Middle Ages helped to lay the groundwork for modern historical historiography, providing vital accounts of the early history of England, Wales and Normandy, its cultures, and revelations about the historians themselves.

The term Middle English literature refers to the literature written in the form of the English language known as Middle English, from the late 12th century until the 1470s. During this time the Chancery Standard, a form of London-based English, became widespread and the printing press regularized the language. Between the 1470s and the middle of the following century there was a transition to early Modern English. In literary terms, the characteristics of the literary works written did not change radically until the effects of the Renaissance and Reformed Christianity became more apparent in the reign of King Henry VIII. There are three main categories of Middle English literature, religious, courtly love, and Arthurian, though much of Geoffrey Chaucer's work stands outside these. Among the many religious works are those in the Katherine Group and the writings of Julian of Norwich and Richard Rolle.

The Brut or Roman de Brut by the poet Wace is a loose and expanded translation in almost 15,000 lines of Norman-French verse of Geoffrey of Monmouth's Latin History of the Kings of Britain. It was formerly known as the Brut d'Engleterre or Roman des Rois d'Angleterre, though Wace's own name for it was the Geste des Bretons, or Deeds of the Britons. Its genre is equivocal, being more than a chronicle but not quite a fully-fledged romance.

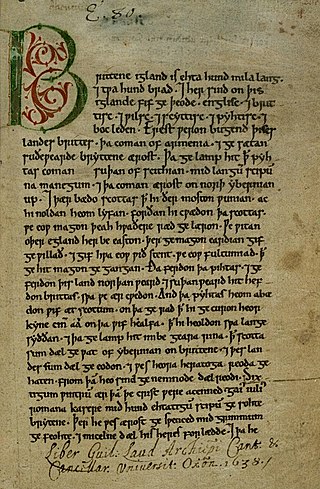

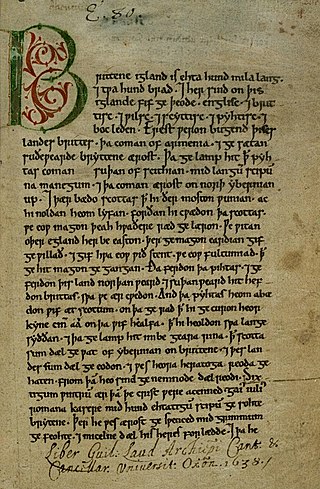

Layamon's Brut, also known as The Chronicle of Britain, is a Middle English alliterative verse poem compiled and recast by the English priest Layamon. Layamon's Brut is 16,096 lines long and narrates a fictionalized version of the history of Britain up to the Early Middle Ages. It was the first work of history written in English since the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle. Named for Britain's mythical founder, Brutus of Troy, the poem is largely based on the Anglo-Norman French Roman de Brut by Wace, which is in turn a version of Geoffrey of Monmouth's Latin Historia Regum Britanniae. Layamon's poem, however, is longer than both and includes an enlarged section on the life and exploits of King Arthur. It is written in the alliterative verse style commonly used in Middle English poetry by rhyming chroniclers, the two halves of the alliterative lines being often linked by rhyme as well as by alliteration.

Albion is an alternative name for Great Britain. The oldest attestation of the toponym comes from the Greek language. It is sometimes used poetically and generally to refer to the island, but is less common than "Britain" today. The name for Scotland in most of the Celtic languages is related to Albion: Alba in Scottish Gaelic, Albain in Irish, Nalbin in Manx and Alban in Welsh and Cornish. These names were later Latinised as Albania and Anglicised as Albany, which were once alternative names for Scotland.

The Historia Regum is a historical compilation attributed to Symeon of Durham, which presents material going from the death of Bede until 1129. It survives only in one manuscript compiled in Yorkshire in the mid-to-late 12th century, though the material is earlier. It is an often-used source for medieval English and Northumbrian history. The first five sections are now attributed to Byrhtferth of Ramsey.

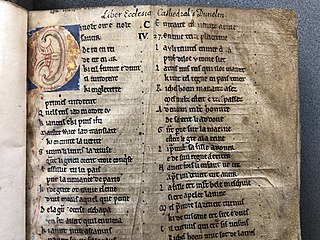

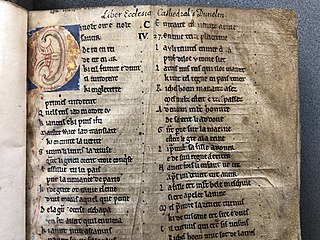

The Liber Eliensis is a 12th-century English chronicle and history, written in Latin. Composed in three books, it was written at Ely Abbey on the island of Ely in the fenlands of eastern Cambridgeshire. Ely Abbey became the cathedral of a newly formed bishopric in 1109. Traditionally the author of the anonymous work has been given as Richard or Thomas, two monks at Ely, one of whom, Richard, has been identified with an official of the monastery, but some historians hold that neither Richard nor Thomas was the author.

Relatio de Standardo, or De bello standardii, is a text composed probably in 1153 or 1154 by the Cistercian monk Aelred of Rievaulx, describing the Battle of the Standard, fought near Northallerton in 1138 between David I, King of Scotland, and a Norman army fighting in support of King Stephen of England.

Brut y Brenhinedd is a collection of variant Middle Welsh versions of Geoffrey of Monmouth's Latin Historia Regum Britanniae. About 60 versions survive, with the earliest dating to the mid-13th century. Adaptations of Geoffrey's Historia were extremely popular throughout Western Europe during the Middle Ages, but the Brut proved especially influential in medieval Wales, where it was largely regarded as an accurate account of the early history of the Celtic Britons.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is a collection of annals in Old English, chronicling the history of the Anglo-Saxons.

The Warkworth's Chronicle, now stylized "Warkworth's" Chronicle, is an English chronicle formerly ascribed to John Warkworth, a Master of Peterhouse, Cambridge. Known from only two manuscripts, it covers the years 1461–1474 and provides information on the recording and reception of historical events including the accession of King Edward IV and the murder of King Henry VI.

A Short English Chronicle is a chronicle produced in England in the first half of the 15th century. It is currently held in Lambeth Palace Library, and although it begins its coverage in 1189, its content is thin until it reaches 1422. It covers the years from then until 1464 in greater depth, ending with the marriage of the Yorkist King Edward IV to Elizabeth Woodville and the capture of the deposed Lancastrian King, Henry VI. It is one of a number of chronicles and writings emitting from London in the early 15th century, and it presents national political events from a London perspective.