Origins and Beliefs

Following the chaos of the November Revolution, and due to the inefficiency of the defeated German army, Einwohnerwehr ("civilian militia", or "civil guard") groups were formed to suppress the revolting Soviet Republics, as well as combat looting and sabotage. The Einwohnerwehr became a powerful force, owning the weapons depots and rising to a membership of 300,000 in Bavaria alone. [1]

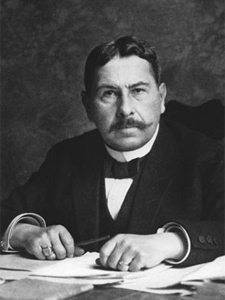

The government later ordered those units dissolved after pressure from the Allies in 1921, and Einwohnerwehr began to form various paramilitary groups. [2] One of the primary successors of the Einwohnerwehr was the Bund Bayern und Reich, formed in 1922. Leadership was initially held by Dr. Georg Escherich and Hermann Kriebel; however these two men, believing themselves too conspicuous, gave command to Dr. Otto Pittinger. [3] Pittinger, a physician who had served as a medical officer in World War I, had formerly led the Organization Pittinger, which protected secret weapon depots owned by Einwohnerwehr. [1] Escherich and Kriebel had hoped Pittinger to be just a front man for them; however, with support from Gustav von Kahr, Pittinger soon became the true leader of the organization. [4]

Bayern und Reich supported pro-monarchist efforts, antisemitism, and sought to fight Marxist elements in Bavaria. It promoted a return to the borders of the German Empire, Christian traditions, and freedom from the limits placed on Germany by the Versailles Treaty. Membership was limited to "Aryans". [5] Their slogan was, "First the Homeland, then the World!" [6]

Among the various "Fatherland societies" that sprung up during this time period, Bayern und Reich was, despite some of its more extreme views, decidedly center. While ready to work through legal or semi-legal methods, it was not above using lobbying tactics or even blackmail. Likewise, while it held nationalist views, it likewise attempted to maintain some of the history and tradition of old Bavaria. [7] This included the restoration of the Bavarian monarchy, [8] and hence they were loyal to the House of Wittelsbach. [9] Over time, many within Bayern und Reich began to push for a separation of Bavaria from Germany until Bolshevism could be countered. [9] [10] Inspiration to split from Berlin was also inspired by the German government's willingness to comply with the Allied demands that the Einwohnerwehr be dissolved. [6]

Political activity

The organization was divided between political and military sub-organizations that were for the most part semi-autonomous. [11] Pittinger ran both the civilian and military activities of the organization, but was advised on military matters by retired lieutenant colonel Paul Schmitt. [12] The military units under Bayern und Reich command were likewise the largest in Bavaria: six infantry regiments, ten signal troops, twelve-and-a-half artillery batteries and one platoon, twenty infantry battalions, sixty-five infantry companies, and the same number of "cadre" units. [13] The organization also had the largest number of arms and weaponry than any other group, with over 65,000 rifles and 1200 machine guns alone. [14]

In the social make-up of Bayern und Reich, the leaders were generally older and better established in life, both in regards to a civilian or military past. It held close connections with wealthy and powerful sponsors, especially those business owners and industrialists who needed protection from leftist rioters. The organization likewise drew many more peasants than the more radical groups, and even attracted such a large group of workers that some left-wing groups complained of Bayern und Reich's reaching power among the working class. [15]

Split

Much of Pittinger's power came from the support of Ritter von Mohl, commanding general of Reichswehr forces in Bavaria. Von Mohl refused to arm or train groups other than Bayern und Reich, hence the need for unity under the organization. [16] However, in 1922 von Mohl was removed from command because of his political activities, and the primary force behind Bayern und Reich's unity was taken away. [17]

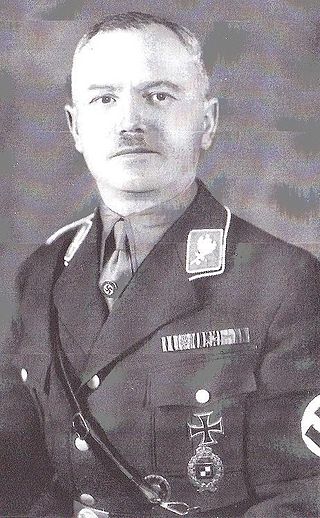

That same year, division was becoming most visible within the organization between right-monarchist factions calling for the restoration of the Wittlesbachs, and the right-radical factions focusing on racial purity and nationalism. [18] The latter factions were largely led by Ernst Röhm and Adolf Heiss. Pittinger and Röhm both had misgivings about the current Weimar government; however, whereas Pittinger was willing to work within the system for change (or as much as was possible), Röhm saw revolution as the only possible policy. [2] The two men continued to clash over various issues, until finally Pittinger accused Röhm of misappropriating goods and funds given for the administration of the Bavarian state, the Reichswehr, and Bayern und Reich. Röhm responded by accusing Pittinger of cowardice and unpatriotic behavior. Finally, Röhm and Heiss split from Bayern und Reich in 1923 and formed the Reichsflagge. Several other, smaller factions split from Bayern und Reich shortly thereafter. [19]

Despite the various splits, Bayern und Reich continued to be the largest paramilitary organization in Bavaria, as well as the one with the most significant position within Bavaria; [12] in the summer of 1923, it boasted nearly 57,000 members in its ranks, [5] with over 37,000 members of military service. [13]

Coup Attempts

At the death of Ludwig III, the last Bavarian monarch, some Bavarians believed that Bayern und Reich would use the situation to start what became nicknamed the Königsputsch ("King Coup"). Reportedly, there was some activity towards this, but the intervention of Crown Prince Rupprecht prevented it. [5]

At the beginning of 1922, Ritter von Kahr was forced to step down as Minister President of Bavaria, and he was replaced by the mild conservative Graf von Lerchenfeld-Köfering. After the assassination of Walther Rathenau, the Jewish foreign minister, the federal government passed the Law for the Protection of the Republic, which increased the punishments for politically motivated acts of violence and banned organizations that opposed the constitutional republican form of government along with their printed material and meetings. Many in right-wing organizations saw their existence threatened. Lerchenfeld, under pressure from the right-wing groups, passed its own Bavarian decree. The federal government reached an agreement that gave Bavaria more control over the cases covered by the law. [20] Bavaria in turn withdrew its own decree, further angering the right-wing groups. [21]

Dissatisfied with the current state of Bavarian politics, and seeking to place von Kahr in control, Pittinger plotted a coup in July 1922. This collapsed in the face of opposition from those in the Reichswehr, including Franz von Epp and the militant Bund Overland. [22]

In August 1922, Pittinger and several other right-wing leaders met at a huge rally in Munich. The rally was entitled For Germany - Against Berlin, and was resolved to defeat "Jewish Bolshevism" seemingly being protected by the government. Among those present was Adolf Hitler, the recently appointed chairman of the quickly growing NSDAP. Hitler's group consisted only in 800 SA men, while Pittinger was present with 30,000. [23] Pittinger hoped to launch a putsch to overthrow the Bavarian government, followed by the Reich government. Hitler, eager to see the Weimar Republic overthrown, agreed to support the coup.

Pittinger, however, began to have misgivings about his putsch, largely stemming from his inability to obtain support from certain sectors. On the eve of the coup, Hitler sent Kurt Ludecke throughout North Germany, alerting nationalists to the upcoming uprising. When Ludecke drove back to Pittinger's place, he found the Bayern und Reich chairman coming out of his house. According to Ludecke, he asked Pittinger, "Is this the coup d'état?" Pittinger simply ignored him, got in his car, and drove off to a vacation in the Alps. In the end, only the National Socialists were ready to march. [24]

Beside Pittinger's withdrawal, the Bayern und Reich putsch failed for a number of reasons: the embarrassing revelation that some conspirators had taken French funds; [22] the discovery of the plan by the police; and a lack of coherency among the various right-wing groups about end goals (e.g., some wanted to restore the Bavarian monarchy, some wanted to unite with Austria in a Catholic state, etc.). [25] Hitler was especially angered by the debacle, both from Pittinger's last-minute withdrawal, as well as the problem of handling various factions. He told Ludecke:

I was ready - my men were ready! From now on I go my way alone. No more Pittingers, no more Fatherland societies! One party. One single party. These gentlemen, these counts and generals - they won't do anything. I shall. I alone. [24]

Beer Hall Putsch

Hitler began to plan his own putsch. Emotions grew with the French invasion of the Ruhr valley, and the seeming weakness of the federal government. With the fear of an uprising from Hitler growing among many in Bavaria, Pittinger promised von Kahr and other leaders that Bayern und Reich would stand with the government. [26] During the putsch itself, Pittinger would go on to warn regiment units in Chiemgau, as well as the Bezirksamt ("district office"), of Hitler's actions. [27]

In the aftermath of the failed putsch, Bayern und Reich continued to distance itself from the more revolutionary elements, and began to cooperate more closely with other monarchist organizations. [1] Because it didn't participate in the putsch, it held its legal status, and continued to be a powerful support base for von Kahr's government, though Pittinger expressed dissatisfaction that von Kahr did not assume full dictatorial powers. [28] The league's moderate politics, while losing members to more radical groups, kept it closely connected with the government and Reichswehr. [29]

Decline

As the organization grew, the military wing required a more elaborate form of leadership; retired general Otto von Stetten was placed in charge of the military branch in 1923, with Lieutenant Colonel Friedrich Preitner serving as his assistant. In June of that year, retired general Ludwig von Tutschek replaced von Stetten. Conflict quickly rose between Pittinger and von Tutschek, due largely to the fact that the power of the military leader was never properly outlined. While Pittinger saw himself as the sole leader of Bayern und Reich, von Tutschek demanded full autonomy over all military concerns. As a result, difficulties grew in the organization, and local branches became more and more difficult to maintain. [12] Ammunition and arms also became a problem, especially after the departure of Röhm, so that at some point Tutschek was eventually told by General Kaiser that Bayern und Reich was now the worst armed of all the paramilitary groups. [14]

Pittinger died while on a return trip from the Adriatic sea in 1926. [30] He was replaced by von Stetten, who was a much weaker leader and organizer than Pittinger. Membership began to drop. [5] The remainder of Bayern und Reich eventually merged with the quickly growing Der Stahlhelm ("The Steel helmet") organization in 1929. The absorption by Stalhlem of Bayern und Reich transformed it from a negligible factor in Bavarian politics into a powerful bloc. [31] The Stahlhelm would eventually merge with the SA in 1935. [1]