In many common law jurisdictions, an indictable offence is an offence which can only be tried on an indictment after a preliminary hearing to determine whether there is a prima facie case to answer or by a grand jury. A similar concept in the United States is known as a felony, which also requires an indictment. In Scotland, which is a hybrid common law jurisdiction, the procurator fiscal will commence solemn proceedings for serious crimes to be prosecuted on indictment before a jury.

Theft is the taking of another person's property or services without that person's permission or consent with the intent to deprive the rightful owner of it. The word theft is also used as a synonym or informal shorthand term for some crimes against property, such as larceny, robbery, embezzlement, extortion, blackmail, or receiving stolen property. In some jurisdictions, theft is considered to be synonymous with larceny, while in others, theft is defined more narrowly. Someone who carries out an act of theft may be described as a thief.

Robbery is the crime of taking or attempting to take anything of value by force, threat of force, or by putting the victim in fear. According to common law, robbery is defined as taking the property of another, with the intent to permanently deprive the person of that property, by means of force or fear; that is, it is a larceny or theft accomplished by an assault. Precise definitions of the offence may vary between jurisdictions. Robbery is differentiated from other forms of theft by its inherently violent nature ; whereas many lesser forms of theft are punished as misdemeanors, robbery is always a felony in jurisdictions that distinguish between the two. Under English law, most forms of theft are triable either way, whereas robbery is triable only on indictment. The word "rob" came via French from Late Latin words of Germanic origin, from Common Germanic raub "theft".

Burglary, also called breaking and entering and sometimes housebreaking, is the act of entering a building or other areas without permission, with the intention of committing a criminal offence. Usually that offence is theft, robbery or murder, but most jurisdictions include others within the ambit of burglary. To commit burglary is to burgle, a term back-formed from the word burglar, or to burglarize.

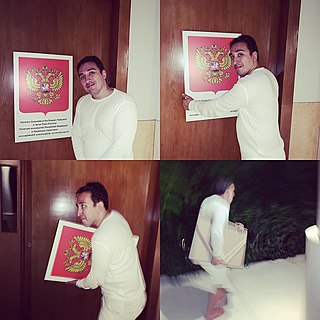

Sacrilege is the violation or injurious treatment of a sacred object, site or person. This can take the form of irreverence to sacred persons, places, and things. When the sacrilegious offence is verbal, it is called blasphemy, and when physical, it is often called desecration. In a less proper sense, any transgression against what is seen as the virtue of religion would be a sacrilege, and so is coming near a sacred site without permission.

The Theft Act 1968 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It creates a number of offences against property in England and Wales. On 15 January 2007 the Fraud Act 2006 came into force, redefining most of the offences of deception.

A hybrid offence, dual offence, Crown option offence, dual procedure offence, offence triable either way, or wobbler is one of the special class offences in the common law jurisdictions where the case may be prosecuted either summarily or as indictment. In the United States, an alternative misdemeanor/felony offense lists both county jail and state prison as possible punishment, for example, theft. Similarly, a wobblette is a crime that can be charged either as a misdemeanor or an infraction, for example, violating COVID-19 safety precautions.

The Theft Act 1978 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It supplemented the earlier deception offences contained in sections 15 and 16 of the Theft Act 1968 by reforming some aspects of those offences and adding new provisions. See also the Fraud Act 2006.

False accounting is a legal term for a type of fraud, considered a statutory offence in England and Wales, Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland.

Possession of stolen goods is a crime in which an individual has bought, been given, or acquired stolen goods.

Property crime is a category of crime, usually involving private property, that includes, among other crimes, burglary, larceny, theft, motor vehicle theft, arson, shoplifting, and vandalism. Property crime is a crime to obtain money, property, or some other benefit. This may involve force, or the threat of force, in cases like robbery or extortion. Since these crimes are committed in order to enrich the perpetrator they are considered property crimes. Crimes against property are divided into two groups: destroyed property and stolen property. When property is destroyed, it could be called arson or vandalism. Examples of the act of stealing property is robbery or embezzlement.

The Penal Code of Singapore sets out general principles of the criminal law of Singapore, as well as the elements and penalties of general criminal offences such as assault, criminal intimidation, mischief, grievous hurt, theft, extortion, sex crimes and cheating. The Penal Code does not define and list exhaustively all the criminal offences applicable in Singapore – a large number of these are created by other statutes such as the Arms Offences Act, Kidnapping Act, Misuse of Drugs Act and Vandalism Act.

Obtaining pecuniary advantage by deception was formerly a statutory offence in England and Wales and Northern Ireland. It was replaced with the more general offence of fraud by the Fraud Act 2006. The offence still subsists in certain other common law jurisdictions which have copied the English criminal model.

R v Collins 1973 QB 100 was a unanimous appeal in the Court of Appeal of England and Wales which examined the meaning of "enters as a trespasser" in the definition of burglary, where the separate legal questions of an invitation based on mistaken identity and extent of entry at the point of that beckoning or invitation to enter were in question.

The Larceny Act 1916 was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Its purpose was to consolidate and simplify the law relating to larceny triable on indictment and to kindred offences.

The Criminal Attempts Act 1981 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It applies to England and Wales and creates criminal offences pertaining to attempting to commit crimes. It abolished the common law offence of attempt.

Removing article from place open to the public is a statutory offence in England and Wales and Northern Ireland.

The Larceny Act 1861 was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. It consolidated provisions related to larceny and similar offences from a number of earlier statutes into a single Act. For the most part these provisions were, according to the draftsman of the Act, incorporated with little or no variation in their phraseology. It is one of a group of Acts sometimes referred to as the Criminal Law Consolidation Acts 1861. It was passed with the object of simplifying the law. It is essentially a revised version of an earlier consolidation Act, the Larceny Act 1827, incorporating subsequent statutes.

Assault with intent to resist arrest is a statutory offence of aggravated assault in England and Wales and Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland.

In English criminal law, an inchoate offence is an offence relating to a criminal act which has not, or not yet, been committed. The main inchoate offences are attempting to commit; encouraging or assisting crime; and conspiring to commit. Attempts, governed by the Criminal Attempts Act 1981, are defined as situations where an individual who intends to commit an offence does an act which is "more than merely preparatory" in the offence's commission. Traditionally this definition has caused problems, with no firm rule on what constitutes a "more than merely preparatory" act, but broad judicial statements give some guidance. Incitement, on the other hand, is an offence under the common law, and covers situations where an individual encourages another person to engage in activities which will result in a criminal act taking place, and intends for this act to occur. As a criminal activity, incitement had a particularly broad remit, covering "a suggestion, proposal, request, exhortation, gesture, argument, persuasion, inducement, goading or the arousal of cupidity". Incitement was abolished by the Serious Crime Act 2007, but continues in other offences and as the basis of the new offence of "encouraging or assisting" the commission of a crime.