Rudolf Lange was a German SS functionary and police official during the Nazi era. With the invasion of the Soviet Union, he served in Einsatzgruppe A before becoming a commander in the Sicherheitsdienst (SD) and all RSHA personnel in Riga, Latvia. He participated in the January 1942 Wannsee Conference, at which the genocidal Final Solution to the Jewish Question was planned, and was largely responsible for implementing the murder of Latvia's Jewish population during the Holocaust.

The ArajsKommando, led by SS commander and Nazi collaborator Viktors Arājs, was a unit of Latvian Auxiliary Police subordinated to the German Sicherheitsdienst (SD). It was a notorious killing unit during the Holocaust.

Friedrich Jeckeln was a German SS commander during the Nazi era. He served as a Higher SS and Police Leader in the occupied Soviet Union during World War II. Jeckeln was the commander of one of the largest groups of Einsatzgruppen death squads and was personally responsible for ordering and organising the deaths of over 100,000 Jews, Romani and others designated by the Nazis as "undesirables". After the end of World War II in Europe, Jeckeln was convicted of war crimes by a Soviet military tribunal in Riga and executed by hanging in 1946.

Herberts Albert Cukurs was a Latvian aviator and Nazi collaborator. He served as the deputy commander of the Arajs Kommando, a collaborationist unit that carried out the largest mass murders of Latvian Jews during the Holocaust. Although Cukurs never stood trial, the accounts of multiple Holocaust survivors, including Zelma Shepshelovitz, credibly link him to personally supervising and committing war crimes and crimes against humanity for the duration of the German occupation of Latvia. His crimes included shooting Jewish children and babies in captivity, burning Jews alive, and sexually assaulting Jewish women.

Eduard Roschmann was an Austrian Nazi SS-Obersturmführer and commandant of the Riga Ghetto during 1943. He was responsible for numerous murders and other atrocities. As a result of a fictionalized portrayal in the novel The Odessa File by Frederick Forsyth and its subsequent film adaptation, Roschmann came to be known as the "Butcher of Riga".

The military occupation of Latvia by Nazi Germany was completed on July 10, 1941, by Germany's armed forces. Initially, the territory of Latvia was under the military administration of Army Group North, but on 25 July 1941, Latvia was incorporated as Generalbezirk Lettland, subordinated to Reichskommissariat Ostland, an administrative subdivision of Nazi Germany. Anyone not racially acceptable or who opposed the German occupation, as well as those who had cooperated with the Soviet Union, was killed or sent to concentration camps in accordance with the Nazi Generalplan Ost.

The history of the Jews in Latvia dates back to the first Jewish colony established in Piltene in 1571. Jews contributed to Latvia's development until the Northern War (1700–1721), which decimated Latvia's population. The Jewish community reestablished itself in the 18th century, mainly through an influx from Prussia, and came to play a principal role in the economic life of Latvia.

The Rumbula massacre is a collective term for incidents on November 30 and December 8, 1941, in which about 25,000 Jews were murdered in or on the way to Rumbula forest near Riga, Latvia, during World War II. Except for the Babi Yar massacre in Ukraine, this was the biggest two-day Holocaust atrocity until the operation of the death camps. About 24,000 of the victims were Latvian Jews from the Riga Ghetto and approximately 1,000 were German Jews transported to the forest by train. The Rumbula massacre was carried out by the Nazi Einsatzgruppe A with the help of local collaborators of the Arajs Kommando, with support from other such Latvian auxiliaries. In charge of the operation was Höherer SS und Polizeiführer Friedrich Jeckeln, who had previously overseen similar massacres in Ukraine. Rudolf Lange, who later participated in the Wannsee Conference, also took part in organizing the massacre. Some of the accusations against Latvian Herberts Cukurs are related to the clearing of the Riga Ghetto by the Arajs Kommando. The Rumbula killings, together with many others, formed the basis of the post-World War II Einsatzgruppen trial where a number of Einsatzgruppen commanders were found guilty of crimes against humanity.

Viktors Arājs was a Latvian/Baltic German collaborator and Nazi SS SD officer who took part in the Holocaust during the German occupation of Latvia and Belarus as the leader of the Arajs Kommando. The Arajs Kommando murdered about half of Latvia's Jews.

The Holocaust in Latvia refers to the crimes against humanity committed by Nazi Germany and collaborators victimizing Jews during the occupation of Latvia. From 1941 to 1944, around 70,000 Jews were murdered, approximately three-quarters of the pre-war total of 93,000. In addition, thousands of German and Austrian Jews were deported to the Riga Ghetto.

Following the occupation of Latvia by Nazi Germany in the summer of 1941, the Daugavpils Ghetto was established in an old fortress near Daugavpils. Daugavpils is the second largest city in Latvia, located on the Daugava River in the southeastern, Latgale, region of Latvia. The city was militarily important as a major road and railway junction. Before World War II, Daugavpils was the center of a thriving Jewish community in the Latgale region and one of the most important centers of Jewish culture in eastern Europe. Over the course of the German occupation of Latvia, the vast majority of the Jews of Latgale were killed as a result of the Nazi extermination policy.

The Jelgava massacres were the killing of the Jewish population of the city of Jelgava, Latvia that occurred in the second half of July or in early August 1941. The murders were carried out by German police units under the command of Alfred Becu, with a significant contribution by Latvian auxiliary police organized by Mārtiņš Vagulāns.

The Liepāja massacres were a series of mass executions, many public or semi-public, in and near the city of Liepāja, on the west coast of Latvia in 1941 after the German occupation of Latvia. The main perpetrators were detachments of the Einsatzgruppen, the Sicherheitsdienst (SD), the Ordnungspolizei (ORPO), and Latvian auxiliary police and militia forces. Wehrmacht soldiers and German naval personnel were present during shootings. In addition to Jewish men, women and children (c.5,000), the Germans and their Latvian collaborators also killed Roma (c.100), communists, the mentally ill (c.30) and so-called "hostages". In contrast to most other Holocaust murders in Latvia, the killings at Liepāja were done in open places. About 5,000 of the 5,700 Jews trapped in Liepāja were shot, most of them in 1941. The killings occurred at a variety of places within and outside of the city, including Rainis Park in the city center, and areas near the harbor, the Olympic Stadium, and the lighthouse. The largest massacre, of 2,731 Jews and 23 communists, occurred in the dunes surrounding the town of Šķēde, north of the city center. This massacre, which was perpetrated on a disused Latvian Army training ground, was conducted by German and collaborator forces from December 15 to 17, 1941. More is known about the killing of the Jews of Liepāja than in any other city in Latvia except for Riga.

The Dünamünde Action was an operation launched by the Nazi German occupying force and local collaborationists in Biķernieki forest, near Riga, Latvia. Its objective was to execute Jews who had recently been deported to Latvia from Germany, Austria, Bohemia and Moravia. These murders are sometimes separated into the First Dünamünde Action, occurring on March 15, 1942, and the Second Dünamünde Action on March 26, 1942. About 1,900 people were killed in the first action and 1,840 in the second. The victims were lured to their deaths by a false promise that they would receive easier work at a (non-existent) resettlement facility near a former neighbourhood in Latvia called Daugavgrīva (Dünamünde). Rather than being transported to a new facility, they were trucked to woods north of Riga, shot, and buried in previously dug mass graves. The elderly, the sick and children predominated among the victims.

Riga Ghetto was a small area in Maskavas Forštate, a neighbourhood of Riga, Latvia, where Nazis forced Jews from Latvia, and later from Germany, to live during World War II. On October 25, 1941, the Nazis relocated all Jews from Riga and its vicinity to the ghetto and its non-Jewish inhabitants were evicted. Most Latvian Jews were killed on November 30 or December 8, 1941, in the Rumbula massacre. The Nazis transported a large number of German Jews to the ghetto; most of them were later killed in massacres.

Otto-Heinrich Drechsler was the General Commissioner of Latvia for the Nazi Germany's occupation regime during World War II. In this capacity, he played a role in setting up the Riga ghetto and was implicated in the extermination of Latvian Jews. He committed suicide on 5 May 1945, after being captured by British forces.

Salaspils camp was established at the end of 1941 at a point 18 km (11 mi) southeast of Riga (Latvia), in Salaspils. The Nazi bureaucracy drew distinctions between different types of camps. Officially, it was the Salaspils Police Prison and Re-Education Through Labor Camp. It was also known as camp Kurtenhof after the German name for the city of Salaspils.

David Silberman is a writer, researcher and a Jewish activist who, having escaped death when the Germans invaded Latvia, gathered and published facts, testimony and documents from survivors of the Holocaust living in Latvia in the 1960s. He had several works published on that theme. Silberman lives in New York, is a US citizen and works as a consultant engineer.

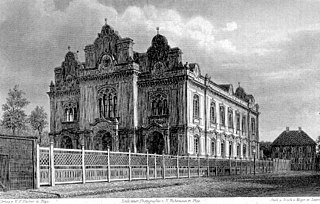

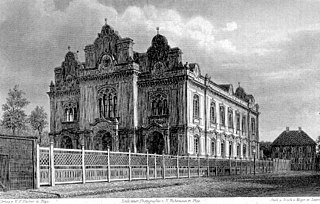

The Great Choral Synagogue on Gogoļa iela was the largest synagogue in Riga, until it was burned down on 4 July 1941.

Frida Michelson was a Latvian Jew and Holocaust survivor. She is known for her memoirs “I survived Rumbula” which records the Holocaust in Latvia, her life in the Riga Ghetto and how she managed to survive the massacre in Rumbula forest. She was one of only two survivors.