An ambulance is a medically equipped vehicle which transports patients to treatment facilities, such as hospitals. Typically, out-of-hospital medical care is provided to the patient during the transport.

A school bus is any type of bus owned, leased, contracted to, or operated by a school or school district. It is regularly used to transport students to and from school or school-related activities, but not including a charter bus or transit bus. Various configurations of school buses are used worldwide; the most iconic examples are the yellow school buses of the United States which are also found in other parts of the world.

The Star of Life is a symbol used to identify emergency medical services. It features a blue six-pointed star, outlined by a white border. The middle contains a Rod of Asclepius – an ancient symbol of medicine. The Star of Life can be found on ambulances, medical personnel uniforms, and other objects associated with emergency medicine or first aid. Elevators marked with the symbol indicate the lift is large enough to hold a stretcher. Medical bracelets sometimes use the symbol to indicate one has a medical condition that emergency services should be aware of.

Type approval or certificate of conformity is granted to a product that meets a minimum set of regulatory, technical and safety requirements. Generally, type approval is required before a product is allowed to be sold in a particular country, so the requirements for a given product will vary around the world. Processes and certifications known as 'type approval' in English are generally called 'homologation', or some cognate expression, in other European languages.

Emergency vehicle lighting, also known as simply emergency lighting or emergency lights, is a type of vehicle lighting used to visually announce a vehicle's presence to other road users. A sub-type of emergency vehicle equipment, emergency vehicle lighting is generally used by emergency vehicles and other authorized vehicles in a variety of colors.

Emergency vehicle equipment is any equipment fitted to, or carried by, an emergency vehicle, other than the equipment that a standard non-emergency vehicle is fitted with.

A nontransporting EMS vehicle, also known as a squad car, fly-car, response vehicle, quick response service (QRS) vehicle, or fast response vehicle, is a vehicle that responds to and provides emergency medical services (EMS) without the ability to transport patients. For patients whose condition requires transport, an ambulance is necessary. In some cases they may fulfill other duties when not participating in EMS operations, such as policing or fire suppression.

Emergency medical services in Canada are the responsibility of each Canadian province or territory. The services, including both ambulance and paramedic services, may be provided directly by the province, contracted to a private provider, or delegated to local governments, which may in turn create service delivery arrangements with municipal departments, hospitals or private providers. The approach, and the standards, vary considerably between provinces and territories.

Emergency medical services in France are provided by a mix of organizations under public health control. The central organizations that provide these services are known as a SAMU, which stands for Service d’aide médicale urgente. Local SAMU organisations operate the control rooms that answer emergency calls and dispatch medical responders. They also operate the SMUR, which refers to the ambulances and response vehicles that provide advanced medical care. Other ambulances and response vehicles are provided by the fire services and private ambulance services.

Emergency Medical Service in Germany is a service of public pre-hospital emergency healthcare, including ambulance service, provided by individual German cities and counties. It is primarily financed by the German public health insurance system.

Emergency medical services in Norway are operated both by the government and private organizations such as the Norwegian People's Aid, the Norwegian Red Cross and commercial transportation companies. In most circumstances, emergency ambulance service is organized by a local Health Trust, and may be operated directly, or contracted to private providers, such as national transportation companies, for which ambulances are just a part of their business operations. Private organisations are also used frequently by the police in search & rescue operations.

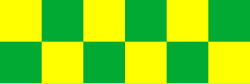

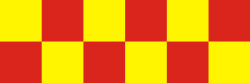

Battenburg markings or Battenberg markings are a pattern of high-visibility markings developed in the United Kingdom in the 1990s and currently seen on many types of emergency service vehicles in the UK, Crown dependencies, British Overseas Territories and several other European countries such as the Czech Republic, Iceland, Sweden, Germany, Romania, Spain, Ireland, and Belgium as well as in New Zealand, Australia, Hong Kong, Trinidad and Tobago, and more recently, Canada. The name comes from its similarity in appearance to the cross-section of a Battenberg cake.

Emergency medical services in Italy currently consist primarily of a combination of volunteer organizations providing ambulance service, supplemented by physicians and nurses who perform all advanced life support (ALS) procedures. The emergency telephone number for emergency medical service in Italy is 118. Since 2017 it has also been possible to call by the European emergency number 112, although this is a general police/fire/medical number.

Emergency medical services in the Netherlands is a system of pre hospital care provided by the government in partnership with private companies.

Ambulance Services in Hong Kong are provided by the Hong Kong Fire Services, in co-operation with two other voluntary organisations, the Auxiliary Medical Service and the Hong Kong St. John Ambulance.

Emergency medical services in Australia are provided by state ambulance services, which are a division of each state or territorial government, and by St John Ambulance in both Western Australia and the Northern Territory.

State Medical Rescue in Poland is a system of free public emergency healthcare established by Ustawa o Państwowym Ratownictwie Medycznym, including ambulance service and Emergency Departments (EDs). While in Polish public hospitals and clinics NFZ common public insurance is required, PRM medical services in ambulances and EDs are completely free for everyone. Since 2018 emergency ambulances that operates in PRM, that is Polish 112 and 999 emergency numbers, are operated by public entities only.

The National Ambulance Service is the statutory public ambulance service in Ireland. The service is operated by the National Hospitals Office of the Health Service Executive, the Irish national healthcare authority.

Emergency Medical Service in Austria is a service of public pre-hospital emergency healthcare, including ambulance service, provided by individual Austrian municipalities, cities and counties. It is primarily financed by the Austrian health insurance companies.

Air medical services are the use of aircraft, including both fixed-wing aircraft and helicopters to provide various kinds of medical care, especially prehospital, emergency and critical care to patients during aeromedical evacuation and rescue operations.