The Tattler is the student newspaper of Ithaca High School in Ithaca, New York. Founded in 1892, it is one of the oldest student newspapers in the United States. It is published twelve times a year and has a circulation of about 3,000, with distribution in both the school and in the community.

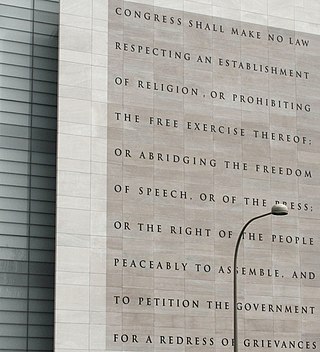

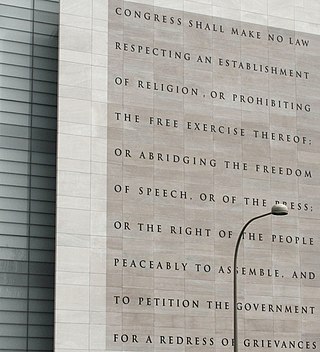

In the United States, freedom of speech and expression is strongly protected from government restrictions by the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, many state constitutions, and state and federal laws. Freedom of speech, also called free speech, means the free and public expression of opinions without censorship, interference and restraint by the government. The term "freedom of speech" embedded in the First Amendment encompasses the decision what to say as well as what not to say. The Supreme Court of the United States has recognized several categories of speech that are given lesser or no protection by the First Amendment and has recognized that governments may enact reasonable time, place, or manner restrictions on speech. The First Amendment's constitutional right of free speech, which is applicable to state and local governments under the incorporation doctrine, prevents only government restrictions on speech, not restrictions imposed by private individuals or businesses unless they are acting on behalf of the government. However, It can be restricted by time, place and manner in limited circumstances. Some laws may restrict the ability of private businesses and individuals from restricting the speech of others, such as employment laws that restrict employers' ability to prevent employees from disclosing their salary to coworkers or attempting to organize a labor union.

Prior restraint is censorship imposed, usually by a government or institution, on expression, that prohibits particular instances of expression. It is in contrast to censorship which establishes general subject matter restrictions and reviews a particular instance of expression only after the expression has taken place.

A student publication is a media outlet such as a newspaper, magazine, television show, or radio station produced by students at an educational institution. These publications typically cover local and school-related news, but they may also report on national or international news as well. Most student publications are either part of a curricular class or run as an extracurricular activity.

Dean v. Utica Community Schools, 345 F. Supp. 2d 799, is a landmark legal case in United States constitutional law, namely on how the First Amendment applies to censorship in a public school environment. The case expanded on the ruling definitions of the Supreme Court case Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier, in which a high school journalism-oriented trial on censorship limited the First Amendment right to freedom of expression in curricular student newspapers. The case consisted of Utica High School Principal Richard Machesky ordering the deletion of an article in the Arrow, the high school's newspaper, a decision later deemed "unreasonable" and "unconstitutional" by District Judge Arthur Tarnow.

Censorship in Iraq has changed under different regimes, most recently due to the 2003 invasion of Iraq.

In the United States, censorship involves the suppression of speech or public communication and raises issues of freedom of speech, which is protected by the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. Interpretation of this fundamental freedom has varied since its enshrinement. Traditionally, the First Amendment was regarded as applying only to the Federal government, leaving the states and local communities free to censor or not. As the applicability of states rights in lawmaking vis-a-vis citizens' national rights began to wane in the wake of the Civil War, censorship by any level of government eventually came under scrutiny, but not without resistance. For example, in recent decades, censorial restraints increased during the 1950s period of widespread anti-communist sentiment, as exemplified by the hearings of the House Committee on Un-American Activities. In Miller v. California (1973), the U.S. Supreme Court found that the First Amendment's freedom of speech does not apply to obscenity, which can, therefore, be censored. While certain forms of hate speech are legal so long as they do not turn to action or incite others to commit illegal acts, more severe forms have led to people or groups being denied marching permits or the Westboro Baptist Church being sued, although the initial adverse ruling against the latter was later overturned on appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court case Snyder v. Phelps.

Censorship in Japan has taken many forms throughout the history of the country. While Article 21 of the Constitution of Japan guarantees freedom of expression and prohibits formal censorship, effective censorship of obscene content does exist and is justified by the Article 175 of the Criminal Code of Japan. Historically, the law has been interpreted in different ways—recently it has been interpreted to mean that all pornography must be at least partly censored, and a few arrests has been made based on this law.

Desilets v. Clearview Regional Board of Education, 137 N.J. 585 (1994), was a New Jersey Supreme Court decision that held that public school curricular student newspapers that have not been established as forums for student expression are subject to a lower level of First Amendment protection than independent student expression or newspapers established as forums for student expression.

The Student Press Law Center (SPLC) is a non-profit organization in the United States that aims to protect press freedom rights for student journalists at high school and university student newspapers. It is dedicated to student free-press rights and provides information, advice and legal assistance at no charge for students and educators.

In Guiles v. Marineau, 461 F.3d 320, cert. denied by 127 S.Ct. 3054 (2007), the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit held that the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution of the United States protect the right of a student in the public schools to wear a shirt insulting the President of the United States and depicting images relating to drugs and alcohol.

Freedom of speech is the concept of the inherent human right to voice one's opinion publicly without fear of government censorship or punishment. "Speech" is not limited to public speaking and is generally taken to include other forms of expression. The right is preserved in the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights and is granted formal recognition by the laws of most nations. Nonetheless, the degree to which the right is upheld in practice varies greatly from one nation to another. In many nations, particularly those with authoritarian forms of government, overt government censorship is enforced. Censorship has also been claimed to occur in other forms and there are different approaches to issues such as hate speech, obscenity, and defamation laws.

The issue of school speech or curricular speech as it relates to the First Amendment to the United States Constitution has been the center of controversy and litigation since the mid-20th century. The First Amendment's guarantee of freedom of speech applies to students in the public schools. In the landmark decision Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District, the U.S. Supreme Court formally recognized that students do not "shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate".

Freedom of expression in Canada is protected as a "fundamental freedom" by section 2 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, however, in practice the Charter permits the government to enforce "reasonable" limits censoring speech. Hate speech, obscenity, and defamation are common categories of restricted speech in Canada. During the 1970 October Crisis, the War Measures Act was used to limit speech from the militant political opposition.

United States obscenity law deals with the regulation or suppression of what is considered obscenity and therefore not protected speech under the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. In the United States, discussion of obscenity typically relates to defining what pornography is obscene, as well as to issues of freedom of speech and of the press, otherwise protected by the First Amendment to the Constitution of the United States. Issues of obscenity arise at federal and state levels. State laws operate only within the jurisdiction of each state, and there are differences among such laws. Federal statutes ban obscenity and child pornography produced with real children. Federal law also bans broadcasting of "indecent" material during specified hours.

The censorship of student media in the United States is the suppression of student-run news operations' free speech by school administrative bodies, typically state schools. This consists of schools using their authority to control the funding and distribution of publications, taking down articles, and preventing distribution. Some forms of student media censorship extend to expression not funded by or under the official auspices of the school system or college.

Hazelwood School District et al. v. Kuhlmeier et al., 484 U.S. 260 (1988), was a landmark decision by the Supreme Court of the United States that held that public school curricular student newspapers that have not been established as forums for student expression are subject to a lower level of First Amendment protection than independent student expression or newspapers established as forums for student expression.

Holmby Productions, Inc. v. Vaughn, 177 Kan. 728 (1955), 282 P.2d 412, is a Kansas Supreme Court case in which the Kansas State Board of Review, the state censorship board, and the attorney defendants appealed the decision of the District Court of Wyandotte County. It was found that the law that allowed the board to deny a request for a permit allowing United Artists to show the motion picture The Moon is Blue in Kansas theaters was unconstitutional, and an injunction was issued prohibiting the defendants from stopping the exhibition of the film in Kansas.

In June 2022, the Viking Saga, the student newspaper of Northwest High School in Grand Island, Nebraska, in the United States, published an issue that discussed Pride Month and other LGBTQ-related topics. In response, the school board and superintendent eliminated the school's journalism program and closed down the paper. The newspaper had been advised that transgender staff should not use their preferred names on bylines, and must use the names they had been given at birth.