The Manhattan Project was a program of research and development undertaken during World War II to produce the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States in collaboration with the United Kingdom and with support from Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project was under the direction of Major General Leslie Groves of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Nuclear physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer was the director of the Los Alamos Laboratory that designed the bombs. The Army component was designated the Manhattan District, as its first headquarters were in Manhattan; the name gradually superseded the official codename, Development of Substitute Materials, for the entire project. The project absorbed its earlier British counterpart, Tube Alloys. The Manhattan Project grew rapidly and employed nearly 130,000 people at its peak and cost nearly US$2 billion. Over 90 percent of the cost was for building factories and to produce fissile material, with less than 10 percent for development and production of the weapons. Research and production took place at more than 30 sites across the United States, the United Kingdom, and Canada.

Ernest Orlando Lawrence was an American nuclear physicist and winner of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1939 for his invention of the cyclotron. He is known for his work on uranium-isotope separation for the Manhattan Project, as well as for founding the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.

Oak Ridge is a city in Anderson and Roane counties in the eastern part of the U.S. state of Tennessee, about 25 miles (40 km) west of downtown Knoxville. Oak Ridge's population was 31,402 at the 2020 census. It is part of the Knoxville Metropolitan Area. Oak Ridge's nicknames include the Atomic City, the Secret City, and the City Behind the Fence.

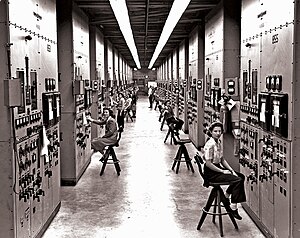

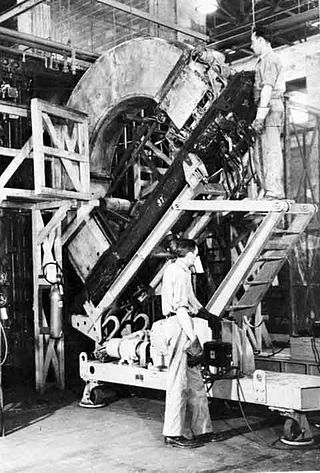

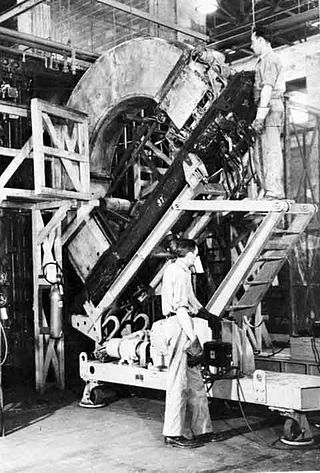

A calutron is a mass spectrometer originally designed and used for separating the isotopes of uranium. It was developed by Ernest Lawrence during the Manhattan Project and was based on his earlier invention, the cyclotron. Its name was derived from California University Cyclotron, in tribute to Lawrence's institution, the University of California, where it was invented. Calutrons were used in the industrial-scale Y-12 uranium enrichment plant at the Clinton Engineer Works in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. The enriched uranium produced was used in the Little Boy atomic bomb that was detonated over Hiroshima on 6 August 1945.

The Y-12 National Security Complex is a United States Department of Energy National Nuclear Security Administration facility located in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, near the Oak Ridge National Laboratory. It was built as part of the Manhattan Project for the purpose of enriching uranium for the first atomic bombs. It is considered the birthplace of the atomic bomb. In the years after World War II, it has been operated as a manufacturing facility for nuclear weapons components and related defense purposes.

The Manhattan Project was a research and development project that produced the first atomic bombs during World War II. It was led by the United States with the support of the United Kingdom and Canada. From 1942 to 1946, the project was under the direction of Major General Leslie Groves of the US Army Corps of Engineers. The Army component of the project was designated the Manhattan District; "Manhattan" gradually became the codename for the entire project. Along the way, the project absorbed its earlier British counterpart, Tube Alloys. The Manhattan Project began modestly in 1939, but grew to employ more than 130,000 people and cost nearly US$2 billion. Over 90% of the cost was for building factories and producing the fissionable materials, with less than 10% for development and production of the weapons.

Walter Guy Roman, was born in Aspen, Colorado and died in Gaithersburg, Maryland. Walter was a son of Erick Roman and Selma Coles.

Major General Kenneth David Nichols CBE was an officer in the United States Army, and a civil engineer who worked on the secret Manhattan Project, which developed the atomic bomb during World War II. He served as Deputy District Engineer to James C. Marshall, and from 13 August 1943 as the District Engineer of the Manhattan Engineer District. Nichols led both the uranium production facility at the Clinton Engineer Works at Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and the plutonium production facility at Hanford Engineer Works in Washington state.

James Edward Westcott was an American photographer who was noted for his work with the United States government in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, during the Manhattan Project and the Cold War.

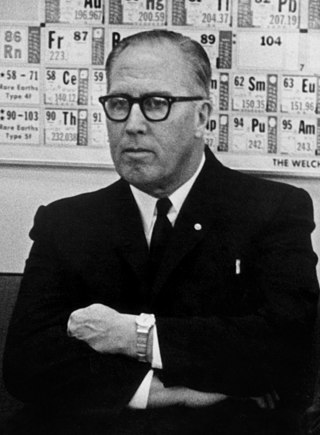

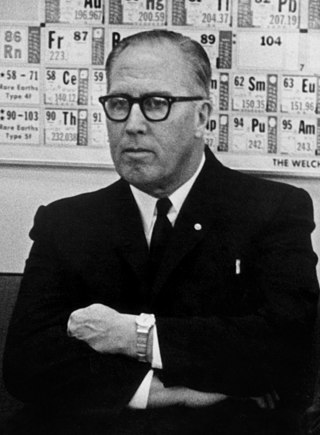

Clarence Edward Larson was an American chemist, nuclear physicist and industrial leader. He was involved in the Manhattan Project, and was later director of Oak Ridge National Laboratory and commissioner of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission.

Ebb Cade was a construction worker at Clinton Engineer Works at Oak Ridge and was the first person subjected to injection with plutonium as an experiment.

Elizabeth Rona was a Hungarian nuclear chemist, known for her work with radioactive isotopes. After developing an enhanced method of preparing polonium samples, she was recognized internationally as the leading expert in isotope separation and polonium preparation. Between 1914 and 1918, during her postdoctoral study with George de Hevesy, she developed a theory that the velocity of diffusion depended on the mass of the nuclides. As only a few atomic elements had been identified, her confirmation of the existence of "Uranium-Y" was a major contribution to nuclear chemistry. She was awarded the Haitinger Prize by the Austrian Academy of Sciences in 1933.

Robert Lyster Thornton was a British-Canadian-American physicist who worked on the cyclotrons at Ernest Lawrence's Radiation Laboratory in the 1930s. During World War II he assisted with the development of the calutron as part of the Manhattan Project. He returned to Berkeley in 1945 to lead the construction of the 184-inch (470 cm) cyclotron, and spent the rest of his career there.

Karl Paley Cohen was a physical chemist who became a mathematical physicist and helped usher in the age of nuclear energy and reactor development. He began his career in 1937 making scientific advances in uranium enrichment as research assistant to Harold Urey, who discovered deuterium–the heavy isotope of hydrogen. Cohen worked within the Columbia group of physicists that included Harold Urey, Enrico Fermi, Leo Szilard, Isidor Isaac Rabi, John R. Dunning, Eugene T. Booth, A. Von Gross and others)–all pioneers of nuclear energy.

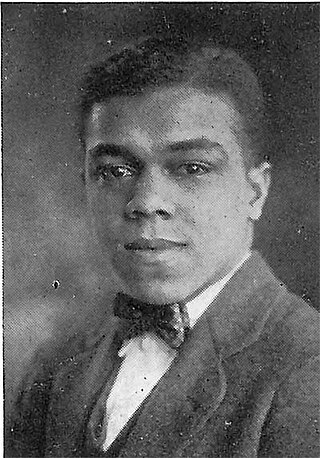

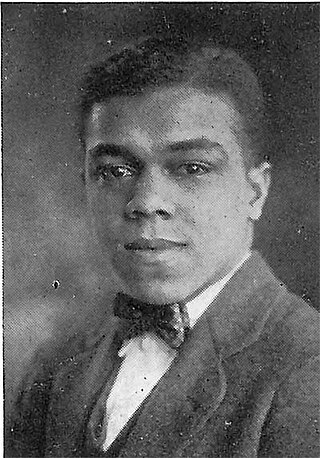

William Jacob Knox Jr. was an American chemist at Columbia University in New York City and one of the African American scientists and technicians on the Manhattan Project. Knox held an unprecedented position, serving as the only African American supervisor for the Manhattan Project. Knox is credited for nuclear research of gaseous diffusion techniques used for the separation of uranium isotopes. Knox's efforts in the development of uranium contributed to the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan, in 1945.

African-American scientists and technicians on the Manhattan Project held a small number of positions among the several hundred scientists and technicians involved. Nonetheless, African-American men and women made important contributions to the Manhattan Project during World War II. At the time, their work was shrouded in secrecy, intentionally compartmentalized and decontextualized so that almost no one knew the purpose or intended use of what they were doing.