Retroactive continuity, or retcon for short, is a literary device in which facts in the world of a fictional work that have been established through the narrative itself are adjusted, ignored, supplemented, or contradicted by a subsequently published work that recontextualizes or breaks continuity with the former.

Star Wars is an American epic space opera media franchise created by George Lucas, which began with the eponymous 1977 film and quickly became a worldwide pop culture phenomenon. The franchise has been expanded into various films and other media, including television series, video games, novels, comic books, theme park attractions, and themed areas, comprising an all-encompassing fictional universe. Star Wars is one of the highest-grossing media franchises of all time.

A pastiche is a work of visual art, literature, theatre, music, or architecture that imitates the style or character of the work of one or more other artists. Unlike parody, pastiche pays homage to the work it imitates, rather than mocking it.

The Wold Newton family is a literary concept derived from a form of crossover fiction developed by the American science fiction writer Philip José Farmer.

A fictional universe is the internally consistent fictional setting used in a narrative work or work of art, most commonly associated with works of fantasy and science fiction. Fictional universes appear in novels, comics, films, television shows, video games, art, and other creative works.

A sequel is a work of literature, film, theatre, television, music or video game that continues the story of, or expands upon, some earlier work. In the common context of a narrative work of fiction, a sequel portrays events set in the same fictional universe as an earlier work, usually chronologically following the events of that work.

A crossover is the placement of two or more otherwise discrete fictional characters, settings, or universes into the context of a single story. They can arise from legal agreements between the relevant copyright holders, common corporate ownership or unofficial efforts by fans.

An alternative universe is a setting for a work of fan fiction that departs from the canon of the fictional universe that the fan work is based on. For example, an AU fan fiction might imagine what would have taken place if the plot events of the source material had unfolded differently, or it might transpose the characters from the original work into a different setting to explore their lives and relationships in a different narrative context. Unlike typical fan fiction, which generally remains within the boundaries of the canon set out by the source material, alternative universe fan fiction writers explore the possibilities of pivotal changes made to characters' history, motivations, or environment, often combining material from multiple sources for inspiration. Characters' known motivations may vary considerably from their decisions in the canonical universe. The author of an alternative universe story thus can use the same characters, but send them down different paths to achieve a completely different plot.

The Star Trek canon is the set of all material taking place within the Star Trek universe that is considered official. The definition and scope of the Star Trek canon has changed over time. Until late 2006, it was mainly composed of the live-action television series and films before becoming a more vague and abstract concept. From 2010 until 2023, the official Star Trek website's site map described their database, which listed both animated and live-action series and films as its sources, as "The Official Star Trek Canon."

The term expanded universe, sometimes called an extended universe, is generally used to denote the "extension" of a media franchise with other media, generally comics and original novels. This typically involves new stories for existing characters already developed within the franchise, but in some cases entirely new characters and complex mythology are developed. This is not necessarily the same as an adaptation, which is a retelling of the same story that may or may not adhere to the accepted canon. It is contrasted with a sequel that merely continues the previous narrative in a linear sequence. Nearly every media franchise with a committed fan base has some form of expanded universe.

A spiritual successor is a product or fictional work that is similar to, or directly inspired by, another previous work, but does not explicitly continue the product line or media franchise of its predecessor, and is thus only a successor "in spirit". Spiritual successors often have similar themes and styles to their source material, but are generally a distinct intellectual property.

The Buffyverse canon consists of materials that are thought to be genuine and those events, characters, settings, etc., that are considered to have inarguable existence within the fictional universe established by the television series Buffy the Vampire Slayer. The Buffyverse is expanded through other additional materials such as comics, novels, pilots, promos and video games which do not necessarily take place in exactly the same fictional continuity as the Buffy episodes and Angel episodes. Star Trek, Star Wars, Stargate and other prolific sci-fi and fantasy franchises have similarly gathered complex fictional continuities through hundreds of stories told in different formats.

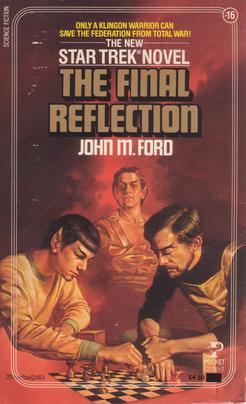

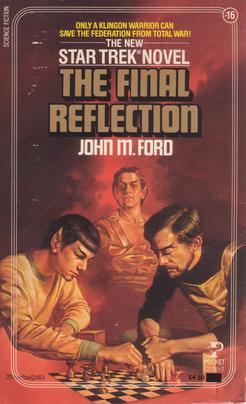

The Final Reflection is a 1984 science fiction novel by American writer John M. Ford, part of the Star Trek franchise. The novel provided the foundation for the FASA Star Trek role-playing game sourcebooks dealing with the Klingon elements of the game. Although not considered canon because of later developments in the Star Trek movies and TV series, the presentation of Klingon culture in this novel and Ford's 1987 follow-on, How Much for Just the Planet? is highly popular in fanon alternate depictions of Klingon society and culture. In particular, the fictional Klingon language klingonaase is introduced here, in advance of the creation of the canon version of the Klingon language, tlhIngan Hol.

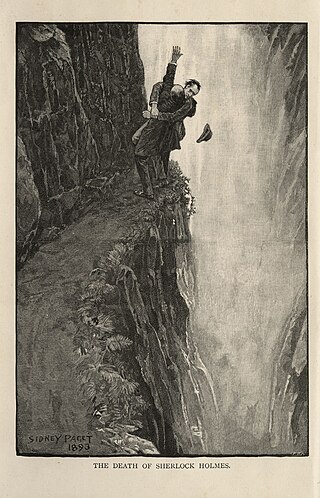

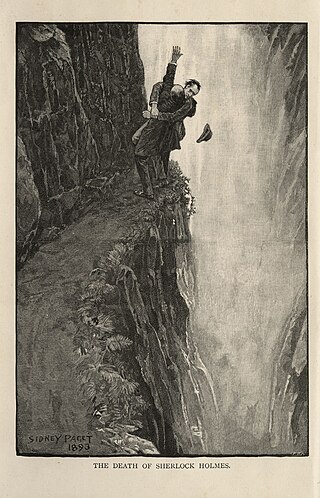

The Sherlockian game is the pastime of attempting to resolve anomalies and clarify implied details about Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson from the 56 short stories and four novels that make up the Sherlock Holmes canon by Arthur Conan Doyle. It treats Holmes and Watson as real people and uses aspects of the canonical stories combined with the history of the era of the tales' settings to construct fanciful biographies of the pair.

A shared universe or shared world is a fictional universe from a set of creative works where one or more writers independently contribute works that can stand alone but fits into the joint development of the storyline, characters, or world of the overall project. It is common in genres like science fiction. It differs from collaborative writing in which multiple artists are working together on the same work and from crossovers where the works and characters are independent except for a single meeting.

Fan fiction or fanfiction is fictional writing written in an amateur capacity by fans, unauthorized by, but based on an existing work of fiction. The author uses copyrighted characters, settings, or other intellectual properties from the original creator(s) as a basis for their writing. Fan fiction ranges from a couple of sentences to an entire novel, and fans can retain the creator's characters and settings and/or add their own. It is a form of fan labor. Fan fiction can be based on any fictional subject. Common bases for fan fiction include novels, movies, comics, musical groups, cartoons, anime, manga, and video games.

Star Wars has been expanded to media other than the original films. This spin-off material is licensed and moderated by Lucasfilm, though during his involvement with the franchise Star Wars creator George Lucas reserved the right to both draw from and contradict it in his own works. Such derivative works have been produced concurrently with, between, and after the original, prequel, and sequel trilogies, as well as the spin-off films and television series. Commonly explored Star Wars media include books, comic books, and video games, though other forms such as audio dramas have also been produced.

A continuation novel is a sequel novel with continuity in the style of an established series, produced by a new author after the original author's death.

Pablo Hidalgo is a Chilean-born creative executive based in California, for Lucasfilm on the Star Wars franchise. He is frequently named as one of the people tasked with maintaining the canon of the franchise after its partial reboot in 2014 and often consults on Star Wars projects in development regarding their integration in the larger Star Wars canon. He is the author of several official references and guidebooks about the Star Wars, G.I. Joe and Transformers franchises.